Twenty years of chasing the Moonby Jeff Foust

|

Technicians examine the heat shields on the Orion spacecraft after the Artemis 1 issue. Concerns about erosion of the heat shield is one reason NASA gave for delaying Artemis 2. (credit: NASA/Skip Williams ) |

Orion problems

The latest change in NASA’s schedule for sending humans back to the Moon came in a media telecon last Tuesday, one that NASA announced at the end of the day the previous Friday—itself a bit of an ominous sign. There was speculation that NASA would announce delays in upcoming Artemis missions, including some who thought NASA would shift the lunar landing mission from Artemis 3 to Artemis 4.

| “As we prepare to send our friends and colleagues on this mission, we’re committed to launching as safely as possible, and we will launch when we’re ready,” said NASA’s Free. |

What NASA did reveal in that call with reporters was both surprising and expected. NASA said that Artemis 2, the first crewed flight of Orion and the Space Launch System that will send four astronauts around the Moon, had been scheduled to launch at the end of this year. Instead, NASA said it will launch no earlier than September 2025, a delay longer than most anticipated.

“Safety is our number one priority,” said Jim Free, who until last month was NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development. (He moved up to the post of NASA associate administrator, the top civil-service position at the agency, upon the retirement of Bob Cabana at the end of 2023.) “As we prepare to send our friends and colleagues on this mission, we’re committed to launching as safely as possible, and we will launch when we’re ready.”

Amit Kshatriya, deputy associate administrator for the Moon to Mars program in the exploration systems development mission directorate, said three issues, all involving Orion, led to the delay. One has been previously discussed by agency officials: unexpected erosion of heat shield material known as Avcoat noticed after Artemis 1’s uncrewed test flight in late 2022. That erosion did not jeopardize the safety of Orion, but NASA wants to better understand what happened and, if necessary, make changes before flying Orion with astronauts on board.

Kshatriya said analysis of the erosion was ongoing and NASA expected to determine a root cause by the spring, the same timeline that his deputy, Lakiesha Hawkins, gave at a meeting of an advisory committee in November. “We have to synthesize that data and update the overall thermal, mechanical, and material models of that heat shield to make sure that, before we attempt reentry from a circumlunar return mission,” he said, “that we’re 100% confident that we understand the performance of that heat shield.”

Two other issues, not previously reported, also contributed to the delay. Kshatriya said that motor valve circuitry used to run valves in Orion’s life support system failed acceptance testing for the spacecraft that will fly the Artemis 3 mission. Subsequent examination found a design flaw in a circuit in those electronics, even though the same component passed acceptance testing for Artemis 2.

Managers decided the best course of action was to redesign and replace the components on both Artemis 2 and 3. “It became clear it was unacceptable for us to accept that hardware and we have to replace it,” he said. That replacement process will be a time-consuming process given the technical challenges in accessing the components in the spacecraft’s current configuration, and he said later that this work drove the schedule to move the launch to next September.

| “Even if we could fly Artemis 2 on the timeframe that we had planned originally, we would still need the extra time to fly Artemis 3,” said Kshatriya. |

A third issue involves the effects of the launch abort system on the spacecraft’s power system. Kshatriya said there were cases where, if the launch abort system was activated, there would be “deficiencies” in the electrical system, particularly with batteries.

“The concern would be not that the vehicle wouldn’t be able to abort safely off of SLS, but that it would be able to maintain all of the power margin that we need from that separation all the way to landing,” he said, noting work on that was still in its early stages, with “multiple parallel options” to fix the issue.

Even without the delat in Artemis 2, NASA says the Artemis 3 launch would have slipped to 2026 because of development delays in the HLS version of Starship. (credit: NASA) |

Artemis 3 and Starship

The slip in Artemis 2 means that Artemis 3, the first crewed landing, is also delayed. That mission was scheduled to launch in late 2025, but NASA said it was now targeted for September 2026, a year after Artemis 2. (Artemis 4, meanwhile, is sticking to its September 2028 launch date.)

However, NASA officials acknowledged that even if Artemis 2 stuck to its earlier schedule, Artemis 3 would still have faced delays. “We need more time on the landing system development and on the suit development,” Kshatriya said. “Even if we could fly Artemis 2 on the timeframe that we had planned originally, we would still need the extra time to fly Artemis 3.” He noted that the new September 2026 date for Artemis 3 “is still very aggressive.”

There is a particular focus on the Human Landing System (HLS) version SpaceX’s Starship, which will take Artemis 3 astronauts down to the lunar surface and back. Starship has flown twice so far, and blown up both times. Moreover, once it starts flying, SpaceX has to demonstrate the ability to fly the vehicle frequently and perform in-space cryogenic propellant transfer, essential for fueling the lunar lander Starship for its journey to the Moon.

Jessica Jensen, vice president of customer operations and integration at SpaceX, played down some of the challenges involved in propellant transfer in particular. “It sounds complex and scary, and it seems like this big, nebulous thing,” she said. “But, when you break it down into its various pieces, we’ve actually achieved almost all of the complex parts already on our operational programs.”

She argued that the company has already demonstrated docking in orbit with its Dragon vehicles delivering cargo and crews to the space station. The high flight rate needed for launching tanker Starships that will transfer propellant is being demonstrated now with Falcon 9, she argued, with launches from different pads hours apart and launches from the same pad just a few days apart.

Just how many launches will be needed has been a subject of debate. At that November committee meeting, NASA’s Hawkins said that the agency believed that number to be in the “high teens,” far higher than what SpaceX had previously stated (see “Starship flies again”, The Space Review, November 20, 2023).

Asked about this in last week’s briefing, Kshatriya said that SpaceX had been “extremely transparent” about the development of Starship, but that a specific number would likely come after flight tests. He deferred to SpaceX’s Jensen, who made the arguments that propellant transfer was not as challenging as it might seem. She did not provide a number.

NASA administrator Bill Nelson then stepped in. “The question was, how many fuel transfers?” He seemed as curious as the reporters on the call for a number.

“Hi Bill,” Jensen responded. “I will say it will roughly be ten-ish.” That number, she added, could go up or down depending on how well the initial flight tests go.

She also noted that Starship will be flying again soon. The hardware for the third integrated test flight will be ready this month, with an updated launch license from the FAA expected by February, once SpaceX completes corrective actions from November’s test flight. “We’re expecting that license to come in February. So, it’s looking like Flight 3 will occur in February.”

Jensen did not disclose what those corrective actions were or other details about what caused the Starship upper stage to explode late in its burn. But in a presentation at SpaceX’s Starbase facility in Boca Chica, Texas, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk said the vehicle caught fire and exploded when it vented liquid oxygen propellant late in the burn.

| “It sounds complex and scary, and it seems like this big, nebulous thing,” Jensen said of in-space refueling. “But, when you break it down into its various pieces, we’ve actually achieved almost all of the complex parts already on our operational programs.” |

“Flight 2 actually almost made it to orbit,” he said in a video the company posted Friday. “If it had a payload, it would have made it to orbit because the reason that it actually didn’t quite make it to orbit was we vented the liquid oxygen, and the liquid oxygen ultimately led to a fire and an explosion.” While he didn’t elaborate on the issue, he appeared to suggest that the liquid oxygen would have been consumed if the vehicle was carrying a payload and needed the additional performance to reach orbit.

That explanation, he said, gave him confidence about the next launch. “I think we’ve got a really good shot of reaching orbit with Flight 3,” he said. That mission will, besides demonstrating the performance of Starship, conduct an in-space burn of its engines to show it can make a controlled deorbit.

It will also test transferring from a header tank at the top of the vehicle to the main tanks. That is a step towards ship-to-ship propellant transfer, he explained. The first ship-to-ship propellant transfer test is expected “hopefully by the end of this year, but certainly by next year.”

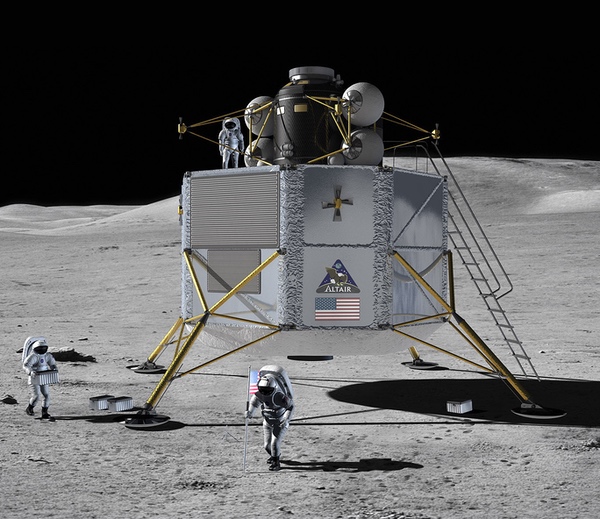

NASA has arguably made more progress with Artemis than the Constellation program, some of whose elements, like the Altair lander, never got beyond the drawing board. (credit: NASA) |

A long-term commitment at long last

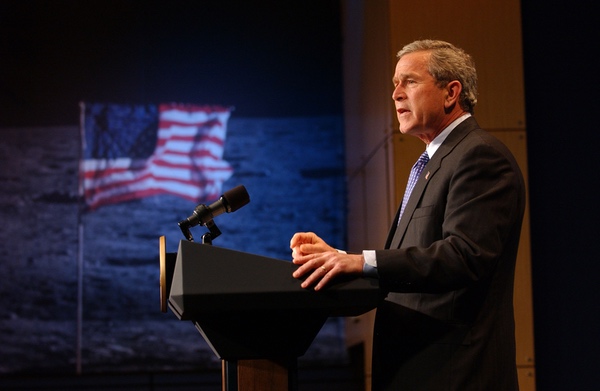

The latest delay can be seen, in one context, as another setback for Artemis. Yet it is also a sign of how much NASA’s plans for returning to the Moon have evolved in the last two decades and, in the process, become more secure.

When Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration in his speech at NASA Headquarters in 2004, he provided milestones and dates but no technical details. He directed NASA to develop a Crew Exploration Vehicle by 2014, but said nothing about it capabilities or requirements.

The Constellation program that emerged from NASA under the leadership of administrator Mike Griffin more than a year and a half later looked remarkably conventional, in retrospect. The Crew Exploration Vehicle became Orion, a modernized version of an Apollo capsule, relying on heavy-lift rockets, Ares I and V, based on shuttle technologies. Development of the Altair lunar lander never got far, but it would have looked much more like the Apollo-era lunar module than Starship or Blue Moon. It was, as Griffin infamously put it, “Apollo on steroids.”

It might well have succeeded in getting humans to the Moon by now given sufficient funding. That funding never materialized and the Obama Administration, acting on the Augustine Commission’s report, decided to give up on Constellation. Orion and the heavy-lift rocket, now SLS, were preserved through a compromise with Congress, but with a focus on asteroids.

| One can argue whether the current Artemis architecture is the best from a technical standpoint, but it shows promise of being sustainable in a way that neither Apollo was nor Constellation could be. |

The Trump Administration directed NASA back to the Moon, but did not revive Constellation. It developed an architecture that gave us the lunar Gateway—keeping ISS partners involved—and commercially developed landers through HLS. NASA originally projected a human lunar return in 2028, after completing the Gateway, only to have the White House move that up to 2024.

Perhaps the biggest step forward in securing NASA’s human return to the Moon is something that didn’t happen. When the Biden Administration took office in 2021, if effectively left what NASA now called Artemis untouched: no change in destinations, dates, or development plans. While the date of the first Artemis crewed landing has slipped from 2024 to now late 2026 (and inevitably, into 2027 or later), that comes from the inexorable creep in any large program, not from major shifts in policy or programmatics.

That is likely to continue: a second Biden term, if he wins reelection in November, will almost certainly keep Artemis on course. If Trump, on the other hand, returns to the White House, he will see a program that looks a lot like the one in place in his first term (and space seems likely to be low on his list of priorities.)

One can argue whether the current Artemis architecture is the best from a technical standpoint. SLS is expensive, Orion continues to have technical problems after more than 15 years of development, and Starship is still unproven. But it shows promise of being sustainable in a way that neither Apollo was nor Constellation could be, an approach that can survive political and technical difficulties.

It may also benefit from perceived competition with China, as that country talks about sending its astronauts to the Moon, possibly as soon as the end of the decade. Nelson, in last week’s call, said he was not worried about China landing astronauts on the Moon before NASA returns: “With us landing in September of ’26, that will be the first landing.” He has, though, used the concept of a new space race with China as an argument with Congress for funding.

“Achieving these goals requires a long-term commitment,” Bush said near the end of his speech at NASA Headquarters 20 years ago. Getting that commitment has long been a challenge for NASA and its advocates, but it may finally be in place when it comes to returning humans to the Moon. The question is less about if it will happen than when.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.