MSR at serious riskby Jeff Foust

|

| Senate appropriators warned last summer that if NASA can’t keep MSR’s costs below $5.3 billion, “NASA is directed to either provide options to de-scope or rework MSR or face mission cancellation.” |

The layoffs were the culmination of two intertwined threads. One is the lack of a fiscal year (FY) 2024 appropriations bill for NASA, and the rest of the federal government, more than four months into the fiscal year. The other is the uncertainty about the future of Mars Sample Return (MSR), one of the biggest programs at the lab.

“While we still do not have an FY24 appropriation or the final word from Congress on our Mars Sample Return (MSR) budget allocation, we are now in a position where we must take further significant action to reduce our spending, which will result in layoffs of JPL employees and an additional release of contractors,” JPL director Laurie Leshin wrote in a memo to lab employees also published online.

Trouble had been brewing about MSR for much of last year. Concerns about the potential of cost growth and schedule delays, including language in NASA’s FY2024 budget proposal that stated that MSR costs “are expected to increase,” prompted NASA’s decision to establish a second independent review board (IRB) to examine the program. The board, led by Orlando Figueroa, former director of Mars exploration at NASA, was charged with assessing the state of MSR.

Even before the completion of that review, the Senate fired a warning shot at the program. In July, a report accompanying the Senate’s proposed 2024 spending bill slashed spending on the program. NASA requested $949.3 million for MSR, an amount the House included in its bill. The Senate bill, though, offered only $300 million for the program.

“The Committee has significant concerns about the technical challenges facing MSR and potential further impacts on confirmed missions, even before MSR has completed preliminary design review,” the Senate report stated. The report would direct NASA to come up with a plan to implement MSR within a cost cap of $5.3 billion, the lifecycle cost included in the planetary science decadal survey published in 2022.

“If NASA is unable to provide the Committee with a MSR lifecycle cost profile within the $5,300,000,000 budget profile,” the report warned, “NASA is directed to either provide options to de-scope or rework MSR or face mission cancellation.”

| “MSR was established with unrealistic budget and schedule expectations from the beginning,” the independent review board report stated. |

A couple months later, the IRB report made clear that Mars Sample Return, as currently designed, had no chance of fitting into that cost cap. The report, released in September, concluded MSR had “a near zero probability” of launching a sample retrieval lander and Earth return orbiter by 2028 as currently planned. It also estimated the total cost of the program at between $8 billion and $11 billion.

“MSR was established with unrealistic budget and schedule expectations from the beginning,” the report stated. “As a result, there is currently no credible, congruent technical, nor properly margined schedule, cost, and technical baseline that can be accomplished with the likely available funding.”

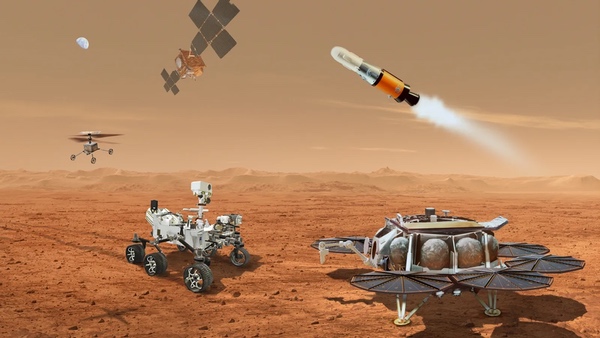

NASA responded to the IRB report by halting plans to hold a confirmation review of MSR, which would have set a formal cost and schedule baseline, that had been scheduled for the fall. Instead, the agency established what it called the MIRT—MSR IRB Response Team, in a nesting of acronyms—to examine alternative options for retrieving the samples currently being cached by the Perseverance rover back to Earth.

“We want to make sure that we’re taking into consideration the findings and recommendations so that we can structure this program to be successful and do so within a balanced budget,” said Sandra Connelly, NASA deputy associate administrator for science, said at a meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG) a few weeks after the release of the report and the establishment of MIRT.

NASA said it expected MIRT to come up with a recommendation for a new approach for MSR by March, which would take advantage as much as possible of the work done to date. “We’re looking to harvest as much of the work that we’ve done to date as possible, but also stepping back and looking at ways we can reduce cost and increase resilience,” said Jeff Gramling, MSR director at NASA headquarters, at the MEPAG meeting.

He also raised a warning about spending. “We don’t know yet what’s going to be appropriated for ’24, so we’re going to have to be skinnying down a bit to fit within ’24 while we pause and step back,” he said.

NASA, like the rest of the federal government, started the 2024 fiscal year last October on a continuing resolution (CR) that funded it at 2023 levels, which for MSR was $822.3 million. But, as Connelly said at a mid-November meeting of NASA’s Planetary Science Advisory Committee, spending at that annualized rate meant NASA could run out of money for the program in months if Congress eventually adopted the lower Senate funding level.

She said at that meeting that NASA was instructing the centers working on MSR, which included JPL as well as Goddard and Marshall, “to start ramping back on activities” to conserve money if that “worst-case scenario” of the Senate bill became reality.

“It’s very unfortunate that we have to make this decision at this point. However, the intent is to enable sufficient funding to carry us throughout the year so we can continue working on and architecting this mission,” she said.

NASA did not disclose by how much it was reducing spending on MSR. But the potential impacts of such reductions alarmed several members of Congress from California, where JPL is based. A little more than a week after Connelly’s announcement at the meeting, a bipartisan group of six members of Congress from the state wrote to NASA administrator Bill Nelson, asking him to restore funding for MSR.

“This short-sighted and misguided decision by NASA will cost hundreds of jobs and a decade of lost science, and it flies in the face of Congressional authority,” they wrote. Regarding the potential job losses, they noted that “this talent represents a national asset that we cannot afford to lose, and if this uniquely talented workforce is lost to the private sector, it will be near impossible to reassemble.”

NASA did not budge, and by early January JPL decided to lay off 100 contractors, most of whom had been working on MSR. The lab had already put a hiring freeze in place and was looking for other ways to reduce spending.

| “We’ve come out now and said, you know, layoffs are looking more likely and there certainly will be some at some of these lower levels of funding,” Leshin said in January. |

“We got direction from NASA to plan for the lower level and we’re doing that systematically,” Leshin said in an interview a few days after the contractor layoffs. Those contractors were used as “surge capacity” on programs, she said, and JPL staff could fill in their roles.

She warned, though, that staff layoffs could follow depending on what happened with the budget. “I wanted to be transparent with the laboratory and we have been all along, saying there’s a lot of uncertainty,” she said. “We’ve come out now and said, you know, layoffs are looking more likely and there certainly will be some at some of these lower levels of funding.”

A majority of California’s congressional delegation—44 members—wrote to the White House February 1, asking Shalanda Young, director of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, to rescind the spending reductions in MSR, making many of the same arguments in the letter to Nelson in February.

But that budget uncertainty still lingers, with the CR funding NASA and many other agencies now extended to March 8. That led to JPL’s decision last week to lay off employees. “So in the absence of an appropriation, and as much as we wish we didn’t need to take this action, we must now move forward to protect against even deeper cuts later were we to wait,” Leshin wrote in the memo announcing the layoffs.

Uncertainty also lingers about MSR itself. The MIRT has been working behind the scenes with few updates about its plans, including what kinds of alternative architectures it is considering. NASA had planned to hold an online town hall meeting in mid-January to discuss the status of the team’s work, but cancelled it.

Leshin said in the January interview that she still expected the review to be completed in March, identifying a more sustainable way to return samples from Mars. “We’re really committed to this high-priority mission—the highest priority two decadal surveys in a row—and to a balanced program,” she said. “I believe there’s a solution out there that will allow us to do that.”

There is also hope that Congress will come through with most or all of the funding NASA requested for MSR. In the White House letter, the California delegation noted that “House Appropriations Committee leadership continue to work closely with their colleagues in the Senate on a compromise position” for MSR funding for 2024, but didn’t specify what that compromise might look like.

“It is our understanding that the modified mission architecture would simplify the program and reduce annual costs, thereby addressing the concerns expressed about MSR in the FY2024 Senate appropriations bill,” the letter also stated, but did not describe what that mission architecture would be.

| Some worry the layoffs may bring a return to an imbalance between JPL’s missions and workforce cited by an earlier review. |

“I'm hopeful in the coming weeks we can work to broker a deal with the Administration and Congress to restore funding to the levels necessary to rehire workers and promote the kinds of scientific discovery JPL has been on the frontlines of for decades,” Rep. Judy Chu (D-CA), whose district includes JPL, said in a statement after the lab announced the layoffs. She was one of the leaders of the earlier letters to Nelson and the White House.

Some privately worry the damage done to the MSR program might be irreparable. The layoffs came after JPL had worked to address other issues at the lab that surfaced when software testing problems delayed the Psyche mission by more than a year. An independent review found, in the words of its chairman, Tom Young, “a large imbalance today between the workload and the available resources at JPL.” (See “The hard truths of NASA’s planetary program”, The Space Review, March 20, 2023.)

JPL worked to address those problems (to the satisfaction of Young and his review board), but that it meant deferring work on the VERITAS Venus orbiter mission by three years to allow JPL to devote its resources on priorities like Europa Clipper, the NISAR Earth science mission—and MSR. (Despite the overall funding uncertainty, Leshin said in January, both NISAR and Europa Clipper are on schedule for launches this spring and October, respectively.)

But solving those problems will be no easier after the layoffs. As one industry source not at JPL said on background, “If JPL had trouble doing all their missions before, how will they manage now with 500 fewer employees?”

The hope in the planetary science community, which has considered returning samples from Mars its top priority among large missions, is that NASA in general, and JPL specifically, will be able to chart a path through this budget, workforce, and mission architecture challenge, finding a more affordable approach that, likely, will take longer to carry out. Those scientists have been waiting for decades for getting samples back from Mars; they may need a little more patience.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.