India unveils its first set of Gaganyaan astronautsby Jatan Mehta

|

| With Gaganyaan, India aims to send its people to space using its own rockets, capsules, and associated technologies. India hopes to clinch this Yuri Gagarin moment of its own by end of 2025, but delays are expected. |

But first, where are the women astronauts? When asked, ISRO says women aren’t in this astronaut batch because being a test pilot was a key requirement, and India had no female test pilots at the time of selection. Well, that might be true, but India does have the highest global percentage of female airline pilots. The fighter pilot number is increasing, too. More firmly, Susmita Mohanty convincingly argues in a piece for The Print how the arbitrary selection criteria doesn’t hold water when compared to initial female astronaut selections worldwide. I agree when Mohanty says: “We have missed a great opportunity as a nation. We could have created history.”

For the benefit of global readers, here’s a brief primer on Indians that have already been to space. Rakesh Sharma was the first Indian to visit Earth orbit, where he spent seven days in 1984 aboard the Soviet Salyut 7 space station. Kalpana Chawla, the first Indian woman in space, held a US citizenship when she flew in 1997 on the Space Shuttle Columbia, the same vehicle Chawla was aboard in 2003, too, but which was destroyed during atmospheric reentry, killing Chawla and her crewmates. Sunita Williams is an Indian-origin but US-born astronaut who is set to fly to the International Space Station again this year aboard the first crewed Starliner flight by Boeing as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew program.

With Gaganyaan, India aims to send its people to space using its own rockets, capsules, and associated technologies. The first crewed Gaganyaan flight will carry no more than two of the four aforementioned astronauts to a 400-kilometer low Earth orbit, where they will spend three days in the Crew Module. If successful, India will then be only the world’s fourth nation to indigenously send humans to space, after Russia, the US, and China. India hopes to clinch this Yuri Gagarin moment of its own by end of 2025, but delays are expected.

For well over a decade, ISRO had been inching towards some baseline technologies necessary to even plan such a massive feat, despite roadblocks and delayed funding. The Indian government finally formally green-lit the human spaceflight program in 2018. Progress on technological components has been faster ever since, with 2022 featuring a successful integrated parachute test demonstrating safe capsule splashdown in the event one of the three main chutes failed to open. More parachute tests followed last year, including tests specific to drogue chutes.

| For well over a decade, ISRO had been inching towards some baseline technologies necessary to even plan such a massive feat, despite roadblocks and delayed funding. |

In February 2023, ISRO began practicing sea recovery trials with a representative crew module, which simulates the mass, center of gravity, size, and externals of the actual Crew Module. In April 2023, ISRO completed human-rating the liquid-fueled Vikas engine after an extensive test period of three years, demonstrating higher structural margins, better health monitoring, off-nominal recoveries, and redundancy in many of its associated systems. Two Vikas engines power the core stage of the Launch Vehicle Mark III (LVM3), India’s most powerful rocket and the vehicle of choice for sending astronauts to space. Likewise in February 2024, ISRO completed human-rating LVM3’s CE-20 cryogenic upper stage engine after a comprehensive set of 39 engine tests.

In May 2023, ISRO qualified the Crew Module’s propulsion system, which will provide controlled atmospheric descent to complete each Gaganyaan flight and bring astronauts back home. In case of an abnormal launch, the same system will keep the crew module stable between a height of 3 to 70 kilometers. In July 2023, ISRO successfully tested the Service Module’s propulsion system (video), which features five 440-newton engines and 16 100-newton reaction control thrusters. During Gaganyaan missions, it’s the service module that will inject astronauts in the Crew Module into orbit, circularize it to a 400-kilometer altitude and maintain it, and eventually provide the deorbit maneuver for the crew module before separating from it.

Launch of a representative Gaganyaan crew module and its attached escape system on October 21, 2023 for an abort test. (credit: ISRO) |

ISRO then conducted a successful abort test in October 2023, which means the crew escape system can safely carry astronauts away from the launch vehicle in the case of an emergency. S. V. Krishna Chaitanya has reported that ISRO’s next step is to better test aspects of the crew module’s parachute system by dropping a representative module from an altitude of four kilometers using a heavy-lift helicopter. This will be followed by another abort test where the escape system will lift the module away while the rocket is on the launchpad itself to simulate pad emergencies. ISRO did conduct one such test in 2018 but this redo is necessary because there have been substantial design changes to Gaganyaan since.

As part of an unprecedented set of broad-sweeping India-US agreements in 2023 centered around collaborative science and technology advancements, NASA will carry one of the four aforementioned Indian astronauts to the International Space Station later this year. NASA and private US companies have also shown interest in leveraging parts of Gaganyaan’s technology stack for a post-ISS future. Chethan Kumar reported last year that Blue Origin and ISRO are interested in using LVM3 to launch crew capsules to service Blue Origin’s upcoming commercial space station, Orbital Reef. Voyager Space announced similar intentions last year for its upcoming Starlab commercial space station, for which it has partnered with Airbus.

| NASA and private US companies have also shown interest in leveraging parts of Gaganyaan’s technology stack for a post-ISS future. |

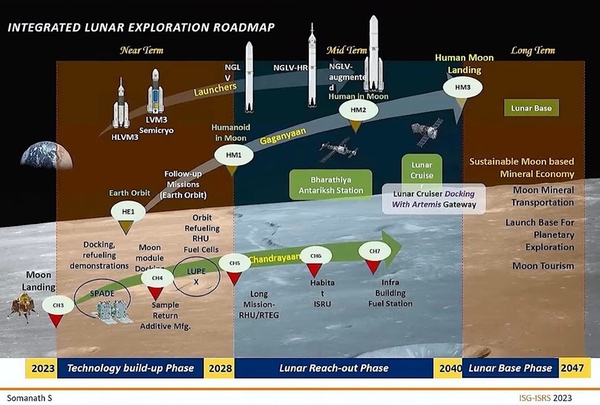

The Indian government directed ISRO in October 2023 to create an Indian Space Station in Earth orbit by 2035, and even send the first Indian to the Moon by 2040. To realize these ambitions, the Indian Department of Space (DOS) and ISRO are developing a roadmap for crewed and lunar exploration, which will comprise an orbital module before the space station, a series of Chandrayaan missions, the development of a partially reusable Next Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV), and more.

Screengrab of a notional integrated lunar and crewed exploration roadmap for India. (credit: S. Somanath / ISRO) |

Despite India’s increasingly complex human spaceflight and planetary exploration ambitions for later this decade and early next, the fiscal year (FY) 2024–25 budget for its Department of Space (DOS)—which includes ISRO’s activities—improved only marginally from $1.51 billion last year to $1.58 billion; even if it may be the interim budget with the national election coming up.

Notably, DOS underutilized its space technology budget in FY 2023–24 by about $150 million, a trait the country’s Ministry of Science & Technology as a whole suffers from. As Mukunth points out in a post, this is but the latest example illustrating that increasing ISRO’s budget alone isn’t a solution in itself for continuing advances in space. Separately, as part of the broader national budget announcement, India’s Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the availability of $12 billion dollars in interest-free loans over 50 years for Indian tech startups, including space ones, to tap into.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.