To the Moon: together or separately?by Jeff Foust

|

| By the time LRO, the first in NASA’s series of lunar missions, launches in 2008, no fewer than four countries will have carried out missions of their own to the Moon. |

While there is as of yet no comprehensive program of lunar exploration, some in ESA are making plans for follow-on missions to SMART-1. Bernard Foing, SMART-1 project scientist, said at the conference that small landers, perhaps featuring rovers, are under consideration: one proposal would land a spacecraft with a 50- to 100-kilogram scientific payload in the polar regions, perhaps using some of the technology to be developed for ESA’s upcoming ExoMars rover mission. Any effort for such a mission, though, would come after ExoMars receives final approval at an ESA ministerial meeting late this year.

The country perhaps most associated today with lunar exploration, outside of the United States, is China. In early 2004 the Chinese government gave its approval for a three-phase robotic lunar exploration program called Chang’e. That program will begin in late 2007 with the launch of Chang’e-1, a lunar orbiter mission; the second and third phases will consist of a lander and a sample return mission; both are planned for the next decade.

A large Chinese contingent was present at the ILC, and offered some insights into the development of the Chang’e-1 orbiter. The spacecraft is based on the DFH-3 communications satellite platform, and will carry seven instruments, including a stereo camera for 3-D imaging, laser altimeter, and various spectrometers and particle detectors. The spacecraft will be launched on a Long March 3A booster and be placed into an elliptical Earth orbit; from there the spacecraft will maneuver into a polar lunar orbit at an altitude of about 200 kilometers for a mission set to last at least one year.

Although there had been media reports prior to the conference that the development of Chang’e-1 had run into problems, the project officials at the Toronto conference said that the program was on schedule. Sun Huixian of the Center for Space Science and Applied Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences said that they had recently completed environmental testing of an engineering model of the spacecraft and encountered “no difficulties” during that process. The Chinese team is now beginning work on the actual flight hardware, while beginning the earliest planning phases for the second mission, a lander.

At the same time that China is developing its first lunar spacecraft, India is doing the same with Chandrayaan-1. This mission, scheduled for launch as early as October 2007, consists of a spacecraft that will fly in a 100-kilometer polar orbit around the Moon for at least two years. Narendra Bhandari, a senior scientist involved with the mission, said at the ILC that the mission’s scientific goals include study of the origin and early evolution of the Moon, its bulk composition, and the transport of volatiles on its surface. The spacecraft will accomplish this with a suite of instruments from India, Europe, and, as currently planned, NASA; the spacecraft will also carry a small impactor probe.

| Although there had been media reports prior to the conference that the development of Chang’e-1 had run into problems, the project officials at the Toronto conference said that the program was on schedule. |

Japan has long set its sights on the Moon, but its lunar exploration program has been subject to extended delays. Nonetheless, officials with the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) at the conference said the agency is pressing ahead with its plans, including the Selenological and Engineering Explorer, or SELENE, mission. Currently scheduled for launch in 2007 on an H-2A booster, SELENE would be a massive spacecraft, weighing 2,885 kilograms at launch. The mission consists of a main orbiter, in a 100-kilometer polar orbit, and two small subsatellites, R* and V*, that serve as a radio relay and gravitational field mapper respectively. The mission will carry 15 instruments to perform a wide-ranging global survey of the Moon.

On the drawing boards for Japan are two follow-on missions. SELENE-2, planned for 2011–2013, would feature a polar lander, while SELENE-3, planned for 2013–2015, would consist of a lander and rover. JAXA’s long-term vision released earlier this year, said Kohtaro Matsumoto, features human missions to the Moon by 2025, although the agency has yet to embark on even conceptual studies for such missions. (Interestingly, the JAXA officials who presented on the status of SELENE made no mention of another Japanese lunar orbiter mission in development, LUNAR-A; it, like SELENE, has encountered significant delays.)

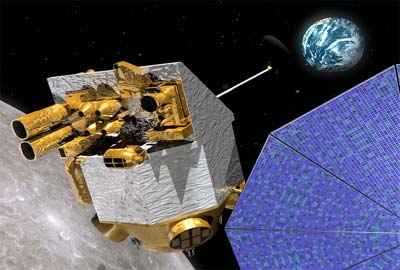

NASA, of course, is back in the lunar exploration business with the Vision for Space Exploration. The agency’s first lunar mission as part of the Vision, LRO, is on track for launch in October 2008, said Mark Borkowski, director of NASA’s Robotic Lunar Exploration Program (RLEP). The spacecraft will carry six major instruments plus one demonstration payload (a miniature synthetic aperture radar), flying in an orbit just 50 kilometers above the surface. At that low altitude LRO will have to perform frequent maneuvers to correct its orbit because of the irregularities of the lunar gravity field; as a result, over half of the spacecraft’s mass, planned to be between 920 and 1,130 kilograms, will be propellant.

LRO is just the beginning of NASA’s robotic lunar exploration plans. The spacecraft will be followed in 2010 by a lander mission, currently known only by the designation RLEP 2. A couple weeks after the conference NASA announced that NASA’s Marshall and Goddard centers will team together to develop the mission. The purpose of the lander, said Borkowski, will be to provide “ground truth” for the data collected by the orbiter, and to demonstrate landing technology that can be used on future missions. The rest of the robotic program is still being defined, he added, and will likely consist of a mix of orbiter and lander missions, along with perhaps sample return missions, to be launched about once every 12 to 18 months.

The role of international cooperation

With all these missions being planned for the Moon, one is left to wonder if there are any synergies that can be exploited and any avenues of international cooperation that can be followed. Comments made by those in attendance at the ILC suggested that there could be an expanded degree of international cooperation in lunar exploration, but that policy barriers, including different goals for each nation’s efforts, may pose a serious obstacle.

| Beyond agreements regarding a few experiments, there has been little concrete cooperation among the various Moon-faring countries. |

There is already a modicum of international cooperation in lunar exploration today. Chandrayaan-1, India’s lunar orbiter, will carry three European instruments under an agreement signed in June between ESA and the Indian space agency ISRO. India has also agreed to fly two NASA instruments, a mineralogical mapper and a version of the mini-SAR that will also fly on LRO, on Chandrayaan-1, although the agreement for their inclusion has yet to be finalized. One of the instruments on LRO, a neutron imager, will be provided by the Russian space science institute IKI.

Beyond that, however, there has been little concrete cooperation among the various Moon-faring countries. Some spoke of nebulous future plans, like ESA’s Foing, who wants to see the development of an “international robotic village” of spacecraft, perhaps at the lunar poles, working on concert. In the near term, one possible cooperative effort would be the exchange of data among countries carrying out lunar missions. Borkowski said he hoped to be able to use international data to select a landing site for the RLEP 2 mission, although some questioned what other nations would get in exchange for providing NASA with such data. “Some of these countries, particularly China and India, are developing their own domestic science capabilities, and want to have their people work on the data” from their missions, rather than turn it over to other countries, said planetary scientist Wendell Mendell of NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

There was also a frustration among some participants about the role of international partners in NASA’s overall Vision for Space Exploration: after over a year and a half since the project’s introduction, there has been no clear delineation of the roles prospective international partners could play in the program. Borkowski, also charged by NASA with presenting the results of the Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS) to conference attendees the same day NASA rolled out the study to the public, sympathized with their concerns. “We really are serious about international cooperation. The challenge with international cooperation always seems to be the timing,” he said. “We are frankly disappointed that we are not able to define clearly more international opportunities.”

Another obstacle to international cooperation is that different countries have different aims for their missions. Spacecraft like Chandrayaan-1 and Chang’e-1 have a series of scientific goals, but are also national prestige missions for their respective countries. LRO, on the other hand, is not primarily a scientific mission, according to Jim Garvin, NASA chief scientist at the time of the conference. “LRO is designed to be a little different,” he said. “It’s designed to mix the science we all know we need to do about the Moon with the applied science and demonstration engineering we need to go back and establish a sustained presence.”

| “We really are serious about international cooperation,” said NASA’s Borkowski. “The challenge with international cooperation always seems to be the timing.” |

However, some remained optimistic that an international framework for cooperation on lunar exploration could be developed. Graham Gibbs, the Canadian Space Agency’s representative in Washington, said that, contrary to conventional wisdom, an approach like that used for the International Space Station could prove successful. “There are some who think the space station is a lesson in what not to do,” he said. “The space station program without question has been a huge technical success and also a huge international cooperation success.” International cooperation here could work through the development of an overarching legal framework, intergovernmental agreements, and bartering (rather than the exchange of funds) among participants, along with, he added, a great deal of “patience, hard work, and willingness to compromise.”

Such cooperation may be essential if smaller nations like Canada—whose annual space agency budget is only about US$250 million—are able to participate in lunar exploration. CSA president Marc Garneau said at the conference that he would like to see Canada play a role in future missions, although he has yet to receive permission from the government to proceed on those plans. That future participation has yet to be defined, but would likely take advantage of Canada’s strengths in space robotics, mining technology, and remote sensing. Garneau made one thing clear, though, in a statement likely shared by other countries seeking to cooperate with the US and other major countries on space exploration: “Canada wants to be a full participant, not a subcontractor.”