The right pathby Eric R. Hedman

|

| If you read a number of the space-related web sites, forums, and blogs, you will find opinions on the direction NASA is going that range from just about perfect to that it will condemn the human race to extinction. I think that this range of opinions would exist no matter what the plans are or become. |

The Planetary Society recently published a statement to Congress with their complaints about the path Michael Griffin is taking. They would like to see the shuttle program ended immediately so there will be no cuts or delays in the unmanned planetary exploration plans. They throw the carrot back to the manned program that the heavy-lift launcher development could start now. They don’t say in the statement how the ISS could be finished, considering the remaining components were designed to be launched and installed by the shuttle. Their comments about developing “international solutions and programs to advance our human space-flight ambitions” are just plain unrealistic if the ISS is going to be finished. The economies of France and Germany are not performing well so I don’t see the European Space Agency getting any great new source of funds. Russia is going to be tying up their resources in developing the Kliper. No other country is ready to be a party in the development of a vehicle to launch and install ISS components.

The Columbia accident has, plain and simple, put NASA in a tough position. Another ten to twelve missions to the ISS could have been completed by now had the flaw in the foam not had such a tragic consequence. NASA has international commitments to complete the ISS. Not completing the ISS would waste the huge investment the US and our partners have put in it. Retiring the shuttle before the ISS is complete is not a realistic option. It would diminish the American space leadership position and NASA’s credibility. It would make it easier to cancel Moon exploration plans when NASA gets into the next budget tight spot or unexpected technological hurdle.

The simple option to continue development of the new launch vehicles without cutting or delaying other programs including aeronautics and science would be to give NASA a big boost in its budget. This is not a realistic option given the cost of the ongoing war, Gulf Coast reconstruction, high deficits, and competing science and research demands from other government agencies. Space science is competing not only against the manned program, but also against other agencies and political realities. NASA also doesn’t have the option of divvying up its programs into budget earmarks that buy reelection for members of Congress the way other programs do. Its budget, like most other agency budgets, is saddled with unconscionable earmarks that have no relationship to the mission of NASA. That practice should be stopped now. If that money could be diverted to science and aeronautics, that would be a good solution.

| The ESAS isn’t the only path that could work, but it can be made to work. There is always a better way to do anything. |

In a world of competing visions and interests somebody has to make the decision as to which path to follow. Right now the person assigned to make the decision with support from the President and oversight by Congress is Michael Griffin. Since there isn’t the money being allocated to make everyone happy, he is going to irritate many people like those in The Planetary Society with his decisions regardless of what they are. As much as I would like to know more about Jupiter’s icy moons and earthlike planets around other stars, I know it’s something I’ll have to wait longer to find out about. A science budget increase slightly below the inflation rate is not an “evisceration” of the program.

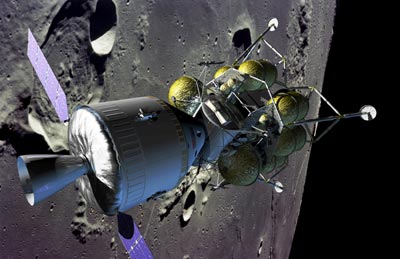

I read through the Exploration Systems Architecture Study as soon as it was posted on the web. For those of you that haven’t, I recommend it. It goes through a logical progression of the roadmap for returning to the Moon and the vehicles needed to do the job. The ESAS explains the overall architecture and the goals it’s designed to meet. It explains why individual components were selected. It explains the selection of the Crew Launch Vehicle choice in comparison to the options of using the Delta or Atlas EELVs. It explains the reasoning behind the choice of engines, propellants, etc.

The ESAS isn’t the only path that could work, but it can be made to work. There is always a better way to do anything. The ESAS had to consider a wide variety of variables covering cost, technical feasibility, existing resources, development time, mission goals, etc. The plan already has had some changes in engine choices, possibly propellant choices, and CEV size. I’m sure there will be further changes as technical, timeline, and budget hurdles pop up. To even put this plan together in the level of detail takes significant prowess that requires an organization with the capabilities of NASA to deliver.

There isn’t one right path for NASA. There are many paths that can work and somebody has to choose a course. The better is always the enemy of the good. Always searching for it can prevent even the good from being accomplished. If I had the time to research all the factors used in the decisions to create the ESAS I might make some different choices than NASA has. And I may also balance funding and timelines with science and aeronautics programs a bit differently if the choice was mine. Most people would come up with some differences to the plans. Given budget realities, the ESAS is forcing tough decisions in other programs within NASA. After reading over the ESAS, I’m confident that it can and probably will work. It won’t make everyone happy, but what does?