Mars abovegroundby Dwayne A. Day

|

| After watching The Mars Underground, many people will be convinced that exploring, settling, and even terraforming Mars is far easier than NASA would have you believe. Heck, I’m a realist and a skeptic, and it almost had me convinced. Almost. |

Although the film is clearly sympathetic to Zubrin and his ideas, to filmmaker Gill’s credit he also interviewed people at NASA who splashed some cold water on Zubrin’s early claims, even while they acknowledged that the core concept was sound. When they actually started crunching the numbers on the Mars Direct proposal they found a number of flaws. For instance, Zubrin’s team had apparently dramatically underestimated the amount of water and food that a crew would need on such a long journey—they’d die of starvation, assuming that they did not die of dehydration first. They also found Zubrin’s launch mass numbers to be too low, and his proposal for a four-man crew was also too small, especially for a very long surface stay. One might suspect that this is a typical bureaucratic not-invented-here reaction, but the people saying this were actually the enthusiasts within the space agency. It is also hard to argue about proper crew size and water requirements with the only people who actually put humans into space on a regular basis. One NASA official commented—with barely-hidden snarkiness—that although it is easy to propose theoretical human spaceflight missions, the people who actually have to make the nuts and bolts fit together have found them to be much harder to do.

One of Zubrin’s public speaking weaknesses is his inability to hide his contempt for anybody who disagrees with him. Most of his verbal ticks don’t come through in the documentary, but his contempt for NASA and those who question his philosophy and technical ideas do rise to the surface at times. A polite way to say it is that he does not suffer fools gladly, except that Zubrin obviously considers the population of fools to be very large. Like many very intelligent people who are passionate about their ideas, he exhibits little patience for those who do not simply take his word that something is possible and want to check his math and maybe his chemistry as well.

But to give him credit, Zubrin’s passion, intelligence, and cleverness are also in evidence in the film. Zubrin’s Mars Direct proposal was adopted by a study team at Johnson Space Center where it was modified to become “Mars Semi-Direct” and incorporated into NASA’s Mars Design Reference Mission. The Design Reference Mission was never more than paper, but it applied more realistic numbers to Zubrin’s idea and demonstrated that a human Mars mission was within the realm of the possible. It may not have busted the NASA paradigm of massively expensive human spaceflight mission concepts, but it put some serious dents in that paradigm.

What the film only touches upon is that many of Zubrin’s ideas have involved a fair degree of hand-waving (or should that be “waiving”?), usually in the form of assuming that because NASA did something once, decades ago, it should be relatively easy to do it again on a much bigger scale. NASA’s entry, descent and landing experts—the handful of people who have actually landed craft on Mars—admit that they do not know how they would land a 40 metric-ton vehicle (about 100 times heavier than the Mars rovers) on the surface of the planet. Heavy tethered, spinning spacecraft have not been flown successfully. Nor do we have the fully autonomous space-rated nuclear reactors that are essential to the Mars Direct scheme. It’s worth noting that all the nuclear reactors that we do have require substantial human tending, something that would not be possible with the time delay to Mars.

Zubrin is also dismissive of those who warn of the radiation dangers to humans on long space journeys, claiming that the people who state that the hazards are real are primarily interested in preserving their own jobs. In one of the more humorous comments of the documentary—one that drew loud laughs from the audience—Zubrin claimed that if NASA sent a crew of smokers to Mars and simply took away their tobacco, it would dramatically decrease their chances of getting cancer.

Why Mars

The documentary does not focus solely on Mars Direct, however. It also deals with Zubrin’s philosophy of why the United States should send humans to Mars, as well as the concept of terraforming, or transforming Mars into a more easily habitable environment.

Over the years Zubrin’s message on why humans should go to Mars (which he thinks should happen sooner rather than some ill-defined “eventually”) has wandered a bit. For many years he argued that it was because the United States was socially and technologically stagnant and had been for a century, since the closing of the Western frontier. These stagnation claims seemed a little odd in the age of cell phones, the Internet, laptop computers, cheap air travel, stealth aircraft, and voting rights for African Americans. Another problem with that argument is that if America does need a new frontier, there is no particular reason why it needs to be Mars. Physical frontiers still exist, although the bottom of the oceans are not as romantic as the plains of Utopia Planitia. Technological challenges also abound as well; the challenges of living on Mars are great, but so are the challenges of bringing water to the Gobi desert or cleaning up the Columbia River, or finding clean alternative sources of energy. Wouldn’t spending $20–30 billion on fusion energy research also produce benefits for humankind?

But the “why Mars” message in the film is the one that Zubrin adopted after the Columbia accident: that a human mission to Mars would give a central driving goal to NASA, which is badly in need of one. Of course, there are other goals, as well as the argument that NASA does not need a new human spaceflight mission, but less human spaceflight in general. Zubrin dismisses exploring the Moon as irrelevant, and the film quotes Planetary Society president Lou Friedman saying that we should go to the Moon before Mars… and we already did, three decades ago—a comment that drew cheers from the Mars Society audience.

| But the “why Mars” message in the film is the one that Zubrin adopted after the Columbia accident: that a human mission to Mars would give a central driving goal to NASA, which is badly in need of one. |

Zubrin believes that Mars exploration is primarily a government activity, funded in the usual manner, and he recognizes the importance of science as a prime reason to go. Whereas other space activists essentially want NASA to turn over billions of dollars of taxpayer money to private entrepreneurs with short or nonexistent track records, Zubrin sees Mars exploration as a more traditional NASA mission, although executed in a non-traditional way. NASA critics will have a harder time accepting Zubrin’s justification, because it is difficult to believe that a space agency as messed up as its harshest libertarian-leaning critics claim should or could conduct such a mission.

Unfortunately, although the film does not make it explicit, in many ways Zubrin is his own worst enemy. He is quick to bite the NASA hand that he wants to feed him—and which has occasionally provided him with small study contracts to conduct demonstration projects. Zubrin received NASA funding to conduct a demonstration project to prove that he could convert carbon dioxide into methane fuel, despite the fact that the chemistry was first practiced over a century ago. When discussing this in front of the camera Zubrin can barely hide his disdain for the people at NASA who actually gave him money. The day after the documentary screening, Zubrin also discussed his clever “Gashopper” project for a Mars airplane using carbon dioxide as propellant, a project that also received NASA funding. Again he demonstrated thinly-veiled contempt for an agency that gave him small amounts of money rather than the bigger amounts he desired. But there is no denying that he’s smart and has the ability to come up with new ideas for doing things.

Mars Underground

The Mars Underground also discusses the origins of the Mars Underground movement itself. Although Zubrin has co-opted the name, the Mars Underground movement actually started in the 1970s when Chris McKay and several other graduate students at the University of Colorado at Boulder held a conference to discuss the exploration of Mars. McKay is interviewed in the film—he has long been a real Mars scientist held in high regard by his fellow Mars scientists—and he too seems at times to express slight skepticism at Zubrin’s ideas. Other members of the original Mars Underground group are not mentioned by name, although they do appear in some humorous photos from the 1970s when very big eyeglasses and plaid were commonplace. They held a series of conferences throughout the1980s and into the 1990s before the movement lost steam—graduate students eventually get jobs far from school, raise families, acquire a mortgage, and are no longer able to spend the time and effort organizing conferences of dreamers.

In the mid-1990s Zubrin picked up the banner and formed the Mars Society, which held its first conference in 1998. (From what I could tell, almost none of the original Mars Underground members were in attendance at the current conference. Considering that the temperature reached 101 degrees in Washington the day of the film screening, nobody can really blame them. Boulder is prettier anyway.)

The documentary also spends a fair amount of time discussing terraforming Mars—adding atmosphere to Mars and heating it up so that it is more easy to inhabit. Here Chris McKay got a laugh from the audience when he was quoted saying that we know that it is possible to heat up the atmosphere of a planet because we’re doing it on Earth. But the film wavers a bit, implying at times that terraforming could be accomplished in perhaps a century but later contradicting this and saying that it might take many centuries. Even if terraforming worked as envisioned by the advocates, the surface of Mars would still be cold and poisonous, and humans would not be able to venture outside without breathing apparatus. Mars would be no more inhabitable than the top of Mount Everest, and in fact might be far less so, given the toxicity of Martian geochemistry.

Zubrin takes all of this in stride and predicts that Mars will be terraformed by the end of the twenty-third century. He also makes the observation that although they may talk about doing this with twenty-first century technologies, it will be done with twenty-second century technologies.

| Although Zubrin has a viable response to the claim that we should not explore space until we have solved our problems on Earth, he doesn’t seem to recognize that when it comes to establishing national priorities in a democracy, terrestrial problems are more convincing to more people than extraterrestrial dreams. |

One of Zubrin’s strengths has been his talent at rebutting specific criticisms of his Mars plans. For instance, to those who claim that Mars is so inhospitable that it requires technology merely to keep people alive, he points out that the same is true for most places on Earth. A human being could not survive a night on a Colorado mountainside without technology—clothes, shelter, the mastery of fire. Although true, the problem is that this criticism is relative, not absolute: merely staying alive on Mars would require far more technology and support than it does on Earth. This is a major reason why the frontier analogy has never worked; settling the American West was relatively easy because settlers did not need to bring their own air, water, and dirt. Food was readily available at the barrel of a gun. Their biggest problem was merely kicking out the natives who already lived there, which also did not require much technology (the Indians had not yet invented the wheel or gunpowder). More importantly, however, the ability to refute critics is not the same as providing a compelling reason to spend tens or more likely hundreds of billions of dollars. Although Zubrin has a viable response to the claim that we should not explore space until we have solved our problems on Earth, he doesn’t seem to recognize that when it comes to establishing national priorities in a democracy, terrestrial problems are more convincing to more people than extraterrestrial dreams.

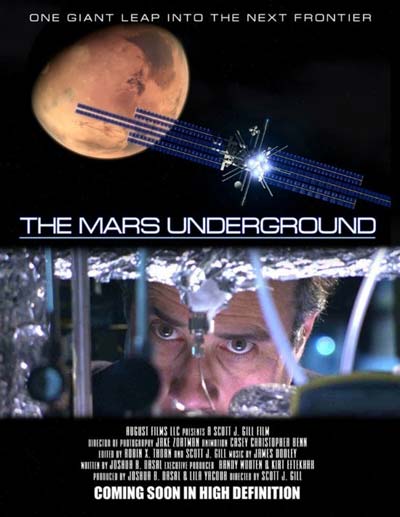

The Mars Underground has excellent production values, including an original soundtrack and some nice cinematography. It also has top-quality computer graphics equal to the best seen in television documentaries today. The computer animations depict a human mission to Mars as well as the growth of a Mars colony and eventual terraforming of the planet. A spacecraft landing sequence was obviously inspired by the exciting graphics produced for Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Mars rover missions. There are a few examples where the film is a little too literal (such as a door slamming shut when the narrator says that NASA slammed the door shut on Zubrin, or a copy of a NASA study resting in a garbage can) and a few relatively minor mistakes (such as showing artist impressions of lunar spacecraft when discussing Mars exploration), but they are relatively trivial. But it is engaging for its entire length of just over an hour, and frequently fun.

According to Scott Gill, he makes his living as a reality television filmmaker, but took time off from his regular job to produce and film The Mars Underground because he loved the subject matter. He found an investor who wanted to do a television pilot about geniuses “and I somehow managed to convince him that Zubrin was a genius,” he joked. He spent a year on the project. One hopes that he can get it to television. Although I don’t buy many of Zubrin’s claims at how relatively easy Mars Direct or even Mars Semi-Direct would be, and although I fear that many more gullible members of the public will swallow the advocacy and ignore the well-founded skepticism voiced by some of the NASA officials interviewed in the documentary, I have to admit that it’s a quality documentary that does a better job explaining both an activist space agenda and possible future human exploration than virtually anything shown on television to date.