Key technologies for Orion and investorsby Taylor Dinerman

|

| A 33 percent return on investment (ROI) is not really big enough to make the normal venture capitalist go wild. For a government program, however, it is quite respectable. |

NASA and its supporters rarely use the phrase “spin-off” to justify the space program today: the idea lost its political salience through overuse. In fact, the greatest side effect of the Moon program was to raise the overall quality and quantity of American science to unprecedented levels. This, in turn, allowed the entrepreneurial sector of the US economy access to ideas and technologies, which could then be turned into profitable enterprises. It has been difficult for economic researchers to find direct links between the spending on the Apollo program and the growth of Silicon Valley and the computer industry, but, as the Soviets used to say, it is no accident that NASA’s Ames Research Center with its specialization in electronic information systems (and a lot else) is in the center of the valley.

Part of the problem might be that we are dealing with the very nature of a capitalist economy. One of the reasons why socialism fails is that there is no way that government-employed economic planners can effectively mimic the billions of decisions, small and large, that take place daily in any complex society. The USSR kept failing as the centralized powers that be in Moscow failed repeatedly to anticipate changes in things as different as the weather, the prices of raw materials, and the desire of workers to be paid and to be able to buy decent consumer goods.

Tracking the climatic effects of a butterfly’s wings may one day be possible. Tracking the economic effects of a government investment on the economy as a whole may be impossible. While most investors may rely on detailed and carefully laid out systems of decision-making, it is doubtful that anything as risky and uncertain as high-tech investing decisions lacks a large emotional content.

In order to take advantage of the exploration program’s requirements, investors will have to take a few factors. First of all, they will need to look for technologies that can be proven in space but that have applications beyond the space industry. For example, a new generation of highly reliable sensors is needed for the fuel tanks and rocket engines of the Ares launch vehicles. The delays that have long characterized shuttle operations are in part due to the unreliability of the many different types of sensors on the vehicle. Years ago aircraft avionics were similarly unreliable (See the first chapter of Tom Wolfe’s classic The Right Stuff) but since the seventies they have improved beyond all recognition.

Other types of technology in which venture capitalists will probably want to look at include new materials, self-repairing structures and mechanisms, and environmental sensing sensors that can detect things like wind shear and other weather-related effects from the moment a rocket lifts off until it leaves the atmosphere.

| Like Apollo the current program’s impact will be hard to measure, but will be evident in the new industries that will spring up around it. |

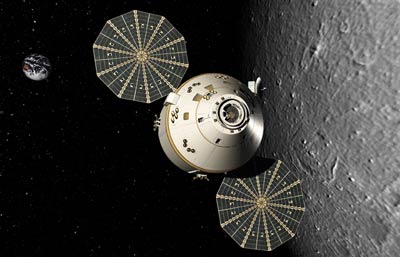

Another point that investors and entrepreneurs will have to keep in mind is that the exploration program is going to last a long time. Apollo lasted from 1961 till 1975, including the Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz missions. After 14 years the program was abandoned, and all that technology was essentially thrown away. Orion, in contrast, is probably going to last thirty years or more, and there will be several generations of Ares launch vehicles, Orion capsules, and Moon landers. There will be plenty of time for investors and entrepreneurs to carefully target the moment during the overall system development when they want to try and induce NASA or its contractors to buy their products. Unlike the tight schedules of most space projects, this will allow companies to take their time and to perfect and certify their technology before trying to sell it.

The real value of the exploration program to the economy will be a subject of debate among experts for many years to come. Like Apollo its impact will be hard to measure, but will be evident in the new industries that will spring up around it. Supporters of the exploration program have long known intuitively that the investments America has made in space technology have helped keep the nation the world’s number one technological superpower. The infinitely complex nature of economic decision-making in a free market system may mean that no one will ever be able to show a direct cause and effect relationship, but that does not mean that it is not there.