The National Space Policy and space arms controlby Nader Elhefnawy

|

| While it is true that some of the new policy’s positions are consistent with those in the 1996 document, there are new claims, like the assertion that “Freedom of action in space is as important to the United States as air power and sea power,” putting space on a par with the other two. |

It can be inferred from this that the US no longer recognizes the right of other sovereign nations to acquire data from space without interference as absolute. At the same time it rejects any restriction on the right of the US not merely to gather data but to engage in any activity in space, as is evident in the changed attitude towards arms control. Where the US would “consider and, as appropriate, formulate policy positions on arms control and related measures governing activities in space” in the 1996 document, the 2006 policy flatly states that the US will oppose “new legal regimes or other restrictions that seek to prohibit or limit U.S. access to or use of space,” and arms control is pointedly included. “Proposed arms control agreements or restrictions must not impair the rights of the United States to conduct research, development, testing, and operations or other activities in space for U.S. national interests.”

In short, there is to be no new restriction on any use of space the US deems vital to its national security, which can be anything at all, explicitly including the research, development, testing, and use of space systems. While space-based and anti-satellite weapons are not specifically referenced, they are also not excluded from that category, which leaves the question of the existing restrictions on these. The 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty having been abrogated in 2001, this means the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST). Article Four of the Outer Space Treaty imposes two main restrictions. The first is a ban on the placement in space of nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction. The second is a ban on the establishment of any kind of military presence (specifically including bases, weapons testing, and the conduct of military maneuvers) on celestial bodies. While it can be argued that the spirit of the treaty is in opposition to the weaponization of space, its letter permits the placement of conventional weapons in Earth orbit, and their use to attack objects in space or on the Earth’s surface.

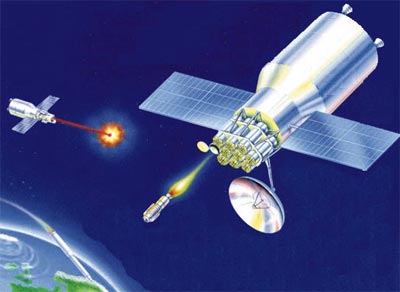

Such capabilities have been elaborately described in recent policy planning papers. It should be remembered that the US has always reserved to itself the right to deploy such systems and pursue such actions, and indeed, during the Cold War developed, tested, and deployed a number of anti-satellite missiles (as did the Soviet Union). The Air Force 2025 paper, published in August 1996, prior to the signing of the last national space policy, declares that “space superiority will be a vital core competency for the US in 2025,” and recommends the development of an array of systems including parasite satellites, transatmospheric vehicles capable of attacking satellites, and ground-based lasers. At the same time it asserts that “weapons use from space will become a reality,” and recommends that the US at the very least be prepared to invest in this capability. Later documents were even more ambitious on this score, and the most extreme space hawks have for years described an omniscient “US Space Force” able to monitor the entire planet and deliver near-instant, devastating strikes against any point on its surface.

Some experts are quick to point out in response that the Pentagon does not presently have an arsenal of such weapons on order, and that in fact many high-profile programs like the Space-Based Laser have been canceled. The absence of present acquisition programs and the termination of specific projects is not necessarily the same as a lack of interest in space forces. On the contrary, several well-publicized and ongoing projects are indicative of such interest, such as the array of directed-energy weapons under development. At least one of these has been tested against satellites (the Mid-Infra-Red Chemical Laser, back in 1997), and this year the Defense Department requested the funding to research dedicated anti-satellite lasers. Another example is the development of the X-37 spaceplane as a future “space bomber,” able to launch from inside the United States and deliver strikes anywhere in the world in as little as ninety minutes after a presidential order. (After languishing for several years, the Air Force revived the X-37 earlier this month as the Orbital Test Vehicle, with its first launch scheduled for 2008.)

It is also possible to see the efforts as being wider than these projects indicate. As Larry Niven once observed, anything worth doing in space can be a weapon, and that certainly applies to other systems, such as the US Air Force’s Autonomous Nanosatellite Guardian for Evaluating Local Space (ANGELS) program, which proposes to use miniature satellites capable of rendezvousing and “piggybacking” with spacecraft to perform inspections of them in the event of possible damage. This capability is precisely what a parasite satellite like those recommended in the Air Force 2025 paper would require. Moreover, even if the US has not yet deployed any such weapons, it has already taken the step of establishing its first military unit dedicated to “offensive and defensive counterspace technology,” the 76th Space Control Squadron, which accomplishes its mission through electronic warfare.

| Nonetheless, explicitly ruling out even the consideration of arms control in the policy is unquestionably a diplomatic and political error, unnecessarily provocative to other states that already view US policy with alarm. |

All of this makes the new policy less of a surprise than a formalization of the movement of the US in this direction, though this is debatable where arms control is concerned. Despite the stated willingness to consider arms control in the previous document, the US government showed little sign of being willing to negotiate this matter long before the release of the new document. The abandonment of the ABM Treaty (much to the chagrin of Russia and China) and the more general refusal of the US to participate in new international agreements must have made it seem highly unlikely that a new agreement would be realized anytime soon.

Nonetheless, explicitly ruling out even the consideration of arms control in the policy is unquestionably a diplomatic and political error, unnecessarily provocative to other states that already view US policy with alarm. For the last several years, Russia and China have been actively trying to build on the OST. On June 27, 2002 they presented a working paper titled “Possible Elements for a Future International Legal Agreement on the Prevention of the Deployment of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects” at the United Nations Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. The paper proposed a treaty obliging signatories not to place “any kinds of weapons” in space or resort to force or the threat of force against space objects. This would rule out attacks on spacecraft by land-, sea-, and air-based systems. Russia and China have also presented a number of follow-up working papers to continue the case for a new agreement, despite US disinterest.

The conventional wisdom appears to be that Russia and China are essentially impotent, and their disapproval irrelevant, which is not accurate. Even if neither they nor any other state is likely to engage the US in an arms race today, they have other options. Professor Robert A. Pape of the University of Chicago recently wrote in the journal International Security about “soft balancing.” Where traditional “hard balancing” in balance of power politics centered on the use or threatened use of military force to counter the power of a threatening state, “soft balancing” involves the use of nonmilitary tools to delay, frustrate, and undermine moves by a state seen as aggressive. The denial of United Nations Security Council approval for the invasion of Iraq by France, Russia, and China, and the refusal of Saudi Arabia and Turkey to provide US forces complete access to their territory, are examples of such soft balancing against the United States prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Even were the cooperation of other countries not needed generally, soft balancing has been occurring in space for decades in the form of other states seeking their own launch capabilities and satellite services to break up what was originally a superpower monopoly. The most dramatic instance of this in recent years is the European Union’s Galileo constellation of navigation satellites, a project intended to reduce its reliance on the Global Positioning System under US Defense Department control, and undertaken despite such strong US disapproval that this alone was thought to have killed it at one point. More vocal than most, President Jacques Chirac of France declared Galileo a necessity to keep Europe from becoming America’s “vassal.” Seeing the usefulness of Galileo’s existence several spacefaring nations outside the EU, including Russia, China, and India, have all supported the project.

Over time soft balancing can turn into hard balancing. While, as stated before, other countries may not be able to engage the US in an arms race, their response need not be an attempt to match the US satellite for satellite, missile for missile, and laser for laser. Regional powers simply do not have to counter global ones on a one-to-one basis, and a “risk fleet” approach, like the one Germany pursued against Britain in World War 1, can tie down larger forces.

Other countries can also invest in approaches that circumvent or overwhelm the space power the US is seeking to build. Both China and Russia are expanding their missile and nuclear capabilities, with the perceived need to be able to overwhelm American missile defenses a likely motive. China’s expansion is particularly problematic because it may encourage neighbors like India to bulk up their own forces. Submarine forces, special-operations forces, and computer warfare afford just a few non-nuclear ways of striking at an opponent about which overwhelming space power can do little.

| A case can be made that the current US lead in resources and technology would be best employed to slow down any further weaponization of space, and that there is a great deal of room for negotiation between the US and Chinese-Russian positions. |

Finally, the reality is that the development of the kind of robust space power envisioned in documents like Air Force 2025 will be realized over decades rather than years, especially space strike capabilities. During that time the balance of economic, military, and technological power could shift considerably, particularly in Asia. By some measures, China’s GDP is already 75 percent that of the US, and it might be the world’s largest economy as early as the 2020s. (By contrast the Soviet economy was never more than 40 percent as big as America’s during the Cold War.) Given its lower per-capita GDP, considerable internal problems, and likely emphasis on continuing to grow its economy rather than bulk up its military forces, China’s military spending is likely to remain lower than that of the US for a long time thereafter, but the gap is still likely to shrink.

In short, the opinions of other countries do matter—and the vision espoused by the hawks is a chimera. A case can be made that the current US lead in resources and technology would be best employed to slow down any further weaponization of space, and that there is a great deal of room for negotiation between the US and Chinese-Russian positions. Indeed, experts have already suggested numerous compromise positions, such as a ban on attacks on unarmed satellites or space-to-Earth weaponry, or a no-first-deployment agreement, all of which would allow missile defense and the use of active measures to protect US satellites. An agreement on space weapons could also be linked to strategic weaponry or other security concerns more generally.

Arms control skeptics typically reply that even if an agreement could be useful, the compliance of other nations would be difficult to verify, and at any rate an agreement may be just a tactic to hamper American efforts while they secretly develop their own capabilities. (See “Space weapons: hardware, paperware, beware?”, The Space Review, November 13, 2006) It is considerably more difficult to inspect for biological and chemical weapons than monitor a space weapons program, however, and as the United Nations’ inspections in Iraq proved, even these can be effective. Additionally, given the inability of any likely rival to compete with the United States in this realm, it seems very unlikely that an arms control proposal would be a realistic way of secretly gaining an advantage. Rather than trying to cheat at the game to secure an advantage, they may be trying to minimize their disadvantage by avoiding the game as much as possible.

Nonetheless, arms control skeptics are correct to point out that such negotiations cannot be isolated from the underlying political issues that made arms control an issue in the first place. In particular, a National Space Policy is going to be subordinate to national policy more generally. The question of what will or will not be done in space depends on larger decisions about how best to provide for the security of the United States. As the predictable responses from both the right and the left following the release of the policy make clear, that other debate will decide the outcome of this one much more than the reverse.