Return to the Moon: for the right reasons, in the right wayby Rick Tumlinson

|

| NASA’s human spaceflight program today is like an old ex-athlete who won the Olympics a long time ago. It is bloated, inflexible, self-indulgent, and lives on reruns of its better days. |

We go to inspire. The most important thing we got out of Apollo was inspiration. It was a star of hope in the darkness of the Cold War. It was the reason I am in this field, and the same goes for many of you reading this. The Internet, telecommunications, the incredible advances in medicine and science, these breakthroughs are coming from organizations whose founders and investors were often born and raised during the Apollo program, and while its legacy was still fresh. If one looks at the numbers of engineers and science students graduated in the US, there is a clear correlation, and right now those numbers are falling, fast.

We go to prepare for even greater things. We cannot throw expendable humans at Mars without knowing what happens to a spacesuit in a high-radiation, high temperature differential, dirty vacuum after it’s been worn and sweated in for six weeks. We need to learn how to operate off-planet, how to build for permanence and how to live off the land in space. Also, those who advocate a direct drive to Mars ignore a major historical fact—the colonies in North America could not have survived without the ports of England and Europe. The development of a strong Earth-LEO-Moon infrastructure, dominated by commercial enterprises, is a necessity, if humans-to-Mars is not to be another unsustainable flags and footprints fiasco or perennial taxpayer funded government housing project.

The “how?” of returning to the Moon partially determines the “why?” For example, if the timeline is too long, the budget too large, the end goal too amorphous, and the whole project is run by the usual suspects in the usual way, the end result will be an uninspiring, over-budget dead end like the International Space Station (ISS). To make a Return to the Moon permanent, inspiring, economical and beneficial to the taxpayers who pay for it all, we must do certain things:

First, we must ignore the whining of those who say they need a lot more money and time. We went from a standing start to standing on the Moon in under ten years—forty years ago! Keep in mind, when Kennedy asked the NASA of that time if it could be done, they told him no, and then they went and did it when ordered to.

Next, we must restructure NASA, as the agency in its current form cannot handle the job. The center-based structure of today must be ended and several non-relevant centers closed or handed over to other agencies. Activities such as aeronautics and Earth studies must be handed off to the FAA and NOAA. Planetary robotic exploration should be given to JPL and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

NASA must shed operational activities such as LEO transport and running the space station. The Orbital Space Plane should be canceled—now. Prizes, multiple source contracts, investment and tax incentives must be put in place to encourage the new “Alt.Space” firms to take over human transport to space, and drive the traditional aerospace giants to modernize or get out of the field. The space station should be mothballed, handed to our partners, or be taken over by a quasi-commercial Space Station Authority as a destination for commercial and university users. ISS and other NASA pet projects must not be grafted onto a moon project simply because they exist. If they really support it they are in, if not, they are out.

What is left should be divided into two parts. The first should be a lean mean human exploration machine that focuses on the “Lewis and Clark function” and acquiring or creating the lowest tech tools possible to travel and explore beyond the Earth. The second should be an agency like the old National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics from which NASA was created. Its job would be to push the envelope of space technologies and systems in support of our space industries.

| ISS and other NASA pet projects must not be grafted onto a moon project simply because they exist. If they really support it they are in, if not, they are out. |

The new NASA would then be one of several players in any RTM project along with DOD, DARPA, NOAA, NSF, universities, and most importantly, the commercial sector. NASA will support planetary transportation systems development, scouting, surveying and pitching the first base camp, then others take over as the agency focuses on developing systems for Mars exploration—its next destination.

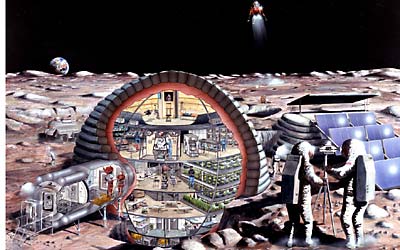

For a Moon base to survive and prosper, it must be built in the right spot, it must be robust, easy to operate at low cost, as self sufficient as possible and be easy to expand. The International Space Station is failing because it is in the wrong place, too delicate, too expensive to operate, and produces nothing of great value, scientific or commercial. To pay for the base we must combine a wide variety of income producing activities and services, such as those listed above. However, the people building the habitats after the first phase, operating the telescopes, and running the facility itself should not be government employees. The long-term lunar facilities should be designed and built by private firms in response to a short list of needs put out by the partners, with the US government leasing those it needs. Long term management of the base should be in the form of a Moon Base Authority to promote new activities, manage infrastructure, oversee safety, and enforce the law.

The bottom line is clear: We must return to the Moon, this time to stay!