Current issues in NewSpaceby Jeff Foust

|

| “The vehicle has to be safe enough to insure,” said XCOR’s Greason. “It’s got to be safe enough to make money.” |

Alex Tai, vice president of operations for Virgin Galactic, said the company didn’t have a specific number of flights in mind SpaceShipTwo would have to complete before being considered safe enough for passengers. “If you have a testing schedule it’s unrealistic to say that you’ll start here and finish there, because you have to be able to react to that testing,” he said. “What I do not want to do is to provide pressure to those engineers to react to unnecessary time scales. They will finish testing when the vehicle is finished. This vehicle will come out when it’s absolutely ready to provide a safety level which is suitable for the investment and for the public.”

Herrington, a former NASA astronaut, noted that during his time with NASA he was told he had a 1-in-400 chance of dying in a shuttle accident. “To me, that was an acceptable risk to do something I had been dreaming about since I was a kid,” he said. “Is that acceptable to us from a business perspective? The answer to that is no.” The RpK business plan calls for a 1-in-10,000 chance of failure.

Jeff Greason of XCOR Aerospace concurred. “The vehicle has to be safe enough to insure,” he said. “It’s got to be safe enough to make money.” Even if there wasn’t outside regulation, he said that they would have to design a vehicle that approaches Herrington’s failure estimate of 1-in-10,000. “If you aren’t that safe, the vehicle doesn’t pay for itself before it crashes. Simple economic self-interest is going to force us to do our very, very best to get the vehicle that safe, and to do enough tests to convince ourselves that it is that safe.”

Beyond vehicle safety, there are other risk factors companies have to deal with—even if those risks are misperceptions. Ron Turner, a scientist with the ANSER Corporation who works on radiation issues, noted that suborbital space tourists would be exposed to minute amounts of additional radiation on their flights: enough to cause only 0.01 fatal cancers per 10,000 passengers. By comparison, 50-year-old white males suffer cancer at the rate of 740 per 10,000 people, with 210 of them fatal; among 30-year-old women of all races, the cancer rate is 150 per 10,000, with 20 fatalities. “The space tourism community does not need to be concerned with the real threat of cancer,” he said. The problem, though, he added, is that people will contract cancer after a spaceflight and assume it was caused by radiation exposure during a flight—particularly for younger people—regardless of the statistics above, and sue accordingly. That makes informed consent releases all the more important, he said.

And just how do potential passengers and the public perceive risk? “Safety will be the ultimate issue at the end of the day,” said George Whitesides, executive director of the National Space Society and one of Virgin Galactic’s first customers. He said that companies should expect potential customers to use “proxy judgments” to determine whether vehicles are safe enough for them to fly: “Will the owner fly? Will they fly their kids? Will the project engineers fly?”

An encroaching concern

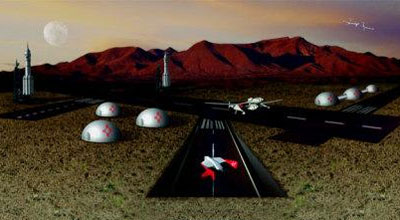

The last year has seen some major developments for commercial spaceports. The Oklahoma Spaceport received its spaceport license from the FAA last June, while Spaceport America in New Mexico got $100 million from the state legislature last spring. Other than a few setbacks (such as the decision last week in Brazoria County, Texas, to end their long-delayed effort to establish a spaceport along the Gulf Coast south of Houston), spaceports are being taken increasingly seriously by some states as a means to diversify their economies and promote the development of aerospace and related high-technology industries.

Some, though, are worried that spaceports will be too successful in that regard, creating development in the immediate vicinity of the spaceport that could, eventually, choke off the spaceport itself. That is a concern at the Mojave Airport and Spaceport in California, home to a number of NewSpace ventures that were attracted to the site not just because of the facilities there but also because of the sparse population and access to uncongested airspace. However, other proposed development in the area has officials concerned about the future.

“As ridiculous as it sounds, houses kill airports, and businesses kill airports,” said Stu Witt, manager of Mojave Airport, citing the problems development has caused to small urban airports, like the one in Santa Monica, California. “Everyone wants to be near the economic engine, which is the airport, and if you allow that to happen, over 50 or 100 years, you don’t have an airport. Someone will close you down.”

“If you had a blank sheet of paper to design for the future,” Witt said, “there would be nothing around it. It’s that simple.”

| “As ridiculous as it sounds, houses kill airports, and businesses kill airports,” said Stu Witt of Mojave Airport. |

That is, in fact, the plan for Spaceport America, said Rick Homans, director of economic development for the state of New Mexico. Current plans limit development around the spaceport out to a radius of 32 kilometers (20 miles). “We don’t want to see a whole lot of commercial development around the spaceport,” he said. “From our perspective what that does is take away one of our strong assets, which is the lack of population, the lack of development. We want to keep it really focused on operations and on experimental flights, and have the economic development take place in the communities.”

The roles of NASA and big aerospace

Many people in NewSpace have mixed opinions, at best, about NASA: while some recall the days when NASA was perceived—rightly or wrongly—as an inhibitor of new space companies, others see the space agency as a potential partner, customer, and even investor. That last attribute has been made possible through the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) demonstration program, where NASA decided last year to award RpK and SpaceX nearly $500 million combined to aid in the development of vehicles that could service the ISS.

While the jury is still out on whether either or both companies were successful, COTS has won over many in the industry. COTS is “the right way to commercialize space,” said Lon Levin, chief strategic officer of Transformational Space LLC (t/Space), one of the finalists in the COTS competition last year. “I have come to believe that the COTS program is the template for how we will commercialize space now and in the future.”

NASA’s investment in COTS has to satisfy what Dennis Stone, assistant manager of the Commercial Crew and Cargo Program Office at the Johnson Space Center, informally called the “Griffin Doctrine”. “When a government undertakes a mission it has to be able to control its destiny to achieve that mission,” said Stone. “But, we will consider purchasing services from the commercial sector if they are available. NASA will consider helping fund the development of those commercial services so that they will be available to buy.”

While RpK and SpaceX were the only companies to have received funded COTS awards (a point of consternation to some in the NewSpace community, who would like to see NASA put more money into the program to fund other competitors), NASA is supporting other companies with unfunded Space Act agreements. In January NASA signed such agreements with two companies, PlanetSpace and t/Space; Stone said discussions with other companies on similar agreements are ongoing.

The potential market for both ISS resupply and commercial orbital missions, such as to orbital habitats planned by Bigelow Aerospace, have also attracted the attention of some decidedly un-NewSpace companies, including United Launch Alliance, the new joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Boeing that is responsible for the manufacturing of the Atlas 5 and Delta 4. ULA, and previously Lockheed, have been studying how to human-rate the Atlas 5 “in the event a passenger vehicle becomes available,” said George Sowers, vice president for business development and advanced programs at ULA.

| Levin: “We have to let go a little of the grandeur of space and focus a bit more on business.” |

Studies to date on using the Atlas 5 401 for human missions have already found ways to eliminate the so-called “black zones” in the flight profile, areas where an abort would result in unsafe conditions for the return of the crew. Those changes, said Sowers, resulted in only a one percent performance penalty for the vehicle. Engineers have also examined how to add an elevator to the service tower currently used for Atlas 5 launches at Cape Canaveral so that crews could access the spacecraft before launch. All the work needed to completely human-rate—a term that is often debated in the industry regarding its exact meaning, and not explicitly defined by Sowers in his presentation—the Atlas 5 could be done by 2010, he said.

Sowers was optimistic that additional demand for the Atlas 5 from commercial orbital manned missions could benefit all users of the vehicle. “The launch vehicle industry is very highly invested in fixed costs,” he said. “If there’s a new big market we think we can get factors of two to four, nearly, in cost reduction by increasing launch rates by factors of two to four.”

The engine of innovation

In a keynote speech to kick off the conference, Antonio Elias of Orbital Sciences Corporation noted that the launch industry has been grappling with the same key technical problems, such as improving specific impulse and mass fraction, for decades with little real evidence of innovation. That’s a far cry from the computer industry, he said, where demand for higher performance has driven many technical innovations, as best exemplified by Moore’s Law. “Unfortunately, right now there aren’t the economic incentives to use those kinds of inventiveness and aggressiveness to solve the real fundamental problems of space transportation,” he said.

Levin, though, was more optimistic that the right incentives for progress are out there. “America has to maintain its dominance in space,” he said. “The great news is that we have a great economic system that can assure our dominance. We should exploit this system to get into space as quick as possible.” He said, though, that we sometimes hinder ourselves by believing that “the grandeur of space” makes the commercialization of space inappropriate. “We have to let go a little of the grandeur of space and focus a bit more on business.”