Opening wallets, closing windowsby Jeff Foust

|

| Marty: “If you want to make a return on launch, there’s an artificial window right now, and the people who make it into that window will benefit, and I think the people who miss that window will miss that opportunity.” |

However, there is growing investor interest in space, driven by the emergence of new markets like space tourism and commercial support for the ISS, as well as the interest in getting into the ground floor of an industry that could grow substantially in the years to come. That interest attracted about 100 people from both the financial and space fields to a one-day Space Investment Summit April 17th in New York City, just down the street from one of the icons of American capitalism, the New York Stock Exchange. The event provided an opportunity to learn about both the investment opportunities that may emerge in the near future as well as the ones whose window of opportunity may be rapidly closing.

A closing launch window

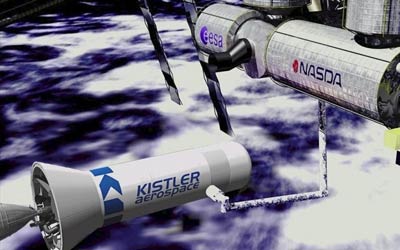

Perhaps the biggest development in NewSpace investment in the last year has been associated with NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation System (COTS) demonstration program. Last August NASA awarded deals worth nearly $500 million combined to Rocketplane Kistler (RpK) and SpaceX to develop vehicles capable of carrying cargo and crew to and from the ISS. These COTS awards alone are not sufficient for either company to develop their designs: they must raise substantial amounts of additional money from other sources, a factor that weighed into NASA’s selection process.

Alan Marty, a former executive in the technology and financial industries who served as an investment consultant to NASA for the COTS program, argued that COTS provided investors with a golden, but limited-time, opportunity. The launch industry, as described by Marty, has very high barriers of entry: an investment of anywhere from 500 million to several billion dollars, “immense” technical expertise, and the ability to provide reliable service to customers who are unforgiving of failure. That makes launch services an unattractive investment given the difficulties involved in competing with those already in the market.

What COTS does, Marty argued, is to artificially and temporarily lower the barriers to entry by providing technical expertise, investment dollars, and “a very substantial, large market” in the form of ISS resupply once the shuttle is retired. “It’s a very fundamental structural change,” he said. However, he said, the barriers to entry will rise again after COTS, giving investors only a limited opportunity to get into the market while conditions remain favorable. “In the near future, when these naturally high barriers to entry reemerge, which they will, anybody who’s able to scoot through this window will not only have a better service and a better cost structure, they will have a long run of very significant profitability.”

Marty made a “comp”—comparison—between COTS and what happened in the semiconductor fabrication industry 20 years ago. Like the launch industry, barriers to entry in the industry were high from technical and financial standpoints: new “fabs” are expensive and difficult to develop. Major customers of existing expensive fab services decided to outsource that work to new low-cost providers, giving those companies funding, technical support, and a promise to purchase semiconductors from them if they could deliver on cost and quality. “I lived through this, I sweated through this 20 years ago,” Marty said.

| “Timing is everything, and the time for space is right now,” said SPACEHAB’s Pickens. |

In this case, two companies, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and United Microelectronics Corp. (UMC), made it though the window of artificially lowered barriers to entry created by this effort. Both companies saw their valuations grow tremendously in the following years: TSMC went from $0.4 billion in 1987 to $28.7 billion in 1997, and is now at about $55 billion, while UMC went from $0.5 billion in 1989 to $88 billion in 2000 (although it has since dropped to only about $13 billion today).

“My point is, there are comps out there that say that if you wait a year, you’ll miss this opportunity,” Marty said. “If you want to make a return on launch, there’s an artificial window right now, and the people who make it into that window will benefit, and I think the people who miss that window will miss that opportunity.” That window, he warned, could close “in the next few months”.

Space as icing on the biotech cake

While space access is certainly the highest profile sector for investment in the space industry, it’s not the only one. Considerable attention at the conference was paid to microgravity research, particularly in the biotech and pharmaceutical industries, an area that has languished for years after long being touted as a key future space industry (see “Medical research on the ISS: will it payoff at last?”, The Space Review, April 23, 2007). That the market is reemerging now, its supporters claim, is simply a matter of timing.

“Timing is everything, and the time for space is right now,” said Thomas Pickens III, the president and CEO of SPACEHAB, a company that announced earlier this month that it was repositioning itself as a provider of space-based manufacturing services. That timing, he said, stems from the availability of the ISS as a platform for microgravity research as well as the emergence of commercial providers, via COTS, to provide commercial transportation services to and from the station.

Those who are interested in space for commercial microgravity research see it as a means to augment, rather than replace, existing terrestrial work in areas like protein crystal growth. “I think we’re making a big mistake if we go around telling companies, ‘We’re going to grow crystals for you in space. Pay me to do this,’” said Larry DeLucas, director of the Center for Biophysical Science and Engineering at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “They’re not going to be eager to do it. They’re going to laugh if they haven’t done it before.”

DeLucas argued that the right approach is to build up technology that allows companies to do similar work on the ground. “We have some unique technologies, and right now we’re spinning off a company that does not need space to succeed,” he said. However, despite that advanced technology, as many as 70 percent of the proteins they try to crystallize on the ground will fail; 60 percent of those, though, could crystallize in microgravity. “That would make a dramatic difference and give us something very unique that space could contribute, but we’re not going to depend on it,” he said. “Space can be, I like to say, the frosting on the cake.”

Like Marty, Pickens argued that there was a limited window of opportunity for companies and investors in this area. “You can’t wait much longer,” he said. “If you do, you’re not going to have a place to play.”

Getting beyond Guadeloupe

But with all the talk about narrow windows of opportunities for investors, there is still very little money flowing yet into this industry from institutional investors. One of the main reasons for this, as many have noted, is that space ventures require long holding periods and offer modest rates of return, neither of which are desirable for those less interested in furthering humanity’s expansion into space than finding a “home run” investment (see “Lawyers, insurance, and money: the business challenges of NewSpace”, The Space Review, March 26, 2007).

| “Space can be, I like to say, the frosting on the cake,” said DeLucas. |

That obstacle was clearly illustrated by John Vornle, president of Long Term Capital Company, as he discussed a proposal presented elsewhere to establish a one-gigawatt solar power station on the Moon that would beam energy back to Earth. While assured by unnamed engineers that such a project was feasible for “only” $11.5 billion (a figure many would consider highly optimistic), he noted that at current electricity rates such a facility would generate earnings of only about $300 million a year, which he said projected to a $3 billion “exit strategy” for investors. “A $3 billion exit strategy for an investment that cost $10 billion to make? Wall Street is not going to be very interested in that. That’s a losing proposition,” he said.

Investors also have to contend with regulatory issues and legal uncertainty not found in other industries. Noted space lawyer Art Dula brought up a common concern for the aerospace industry—export control—and suggested new space companies should consider moving offshore in large part because of it. “I would argue today that the United States is not the venue of choice for a person who wants to start an aerospace startup company,” he said. As an alternative, he suggested the Isle of Man, a Crown dependency of the UK that offers space companies based there a zero-percent tax rate, as well as less-onerous export controls. That company would then contract with an independently-established American company to do business in the US.

Dula also pointed out that while the US has the best-developed space law of any country, there are still a number of key uncertainties in space law and treaties. “We don’t have any definition of where space starts. We don’t have any definition of what, for example, a ‘celestial body’ is. We’re not exactly sure what a ‘space object’ is; it’s not well defined,” he said. “So there’s a great deal of law that we’re going to have to rework over the next few years as this becomes a real business.”

And, for all the renewed interest in space in recent years, the opportunities still seem limited to getting to and working in Earth orbit. Hoyt Davidson, CEO of investment banking and advisory firm Near Earth LLC, drew an analogy with the Treaty of Paris in 1763 that ended the Seven Years War. France was given a choice of keeping either New France, its vast territory in North America, or the small Caribbean island of Guadeloupe. France elected to keep Guadeloupe. “From our standpoint that sounds like a totally outrageous decision, but it’s because we’re sitting here in 2007,” he said. “Back then Guadeloupe had a larger population, was generating more economic wealth, and was certainly easier to get to and to defend.”

Likewise, those who choose to invest in space in the foreseeable future are likely to stick closer to Earth despite the much bigger potential beyond Earth orbit. “The rest of the universe is obviously worth a tremendous amount, but for governments or investors who look at next quarter’s earnings or may have a three- or five-year horizon for their investments, they might choose Guadeloupe,” said Davidson. “So that makes our job a lot harder.”