Phony space weaponization: the case of Radarsat-2by James Oberg

|

| For domestic or international political propaganda profits, innuendo or outright accusations against a project can be issued, perhaps significantly degrading the project’s international partnerships and agreements. |

Two years ago, when NASA’s Deep Impact probe sent a sub-satellite to impact the comet Tempel 1, Egyptian geologist Dr. Zaghlul Al-Naggar told Al-Jazeera TV that it was a weapons test. “The main goal of this operation is military,” he claimed. “America wants to prove to the world that it is capable of hitting a target with a circumference of no more than six kilometers, hundreds of millions of kilometers away. The goal is first and foremost a military one, and its scientific benefit is negligible.” And the “Islamic Community Net” posted a message labeling the event a “planetary death weapons test” which “provided military observers with significant data and analysis concerning the proper design for kinetic energy weapons configured to slam into an Earth ground target, releasing an explosion similar to an atomic weapon.”

Less preposterous were much more widespread weaponry accusations about orbital tests of Pentagon and NASA sensors and robot rendezvous technologies, areas where “dual use” opened a reasonable plausibility that weapons applications could indeed have been imagined. Still, the media accusations often went far off into fantasy, as explained in these articles about the NFIRE and DART missions.

The case against Radarsat-2

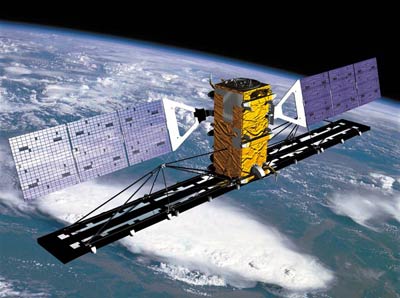

Far more serious is a campaign to classify the Canadian Radarsat earth observation project as a “space weapon”. This is a highly successful and recently commercialized program for radar imaging of the Earth’s surface. It has foreign customers and partners, and some might be put off with association with an alleged “weapon system”, if the accusation developed more traction.

According to the Canadian Space Agency, “RADARSAT-1 is a Canadian-led project involving the Canadian federal government, the Canadian provinces, the United States, and the private sector. It provides useful information to both commercial and scientific users in such fields as disaster management, interferometry, agriculture, cartography, hydrology, forestry, oceanography, ice studies and coastal monitoring.” It was launched in 1995; Radarsat-2 is to be launched later this year with improved capabilities.

The accusation percolated through Canadian “peace websites”, but first seems to have made the major media on December 5, 2004, in the Ottawa Sun. Correspondent Greg Weston of the paper’s “parliamentary bureau” wrote a long piece titled “I SPY, WITH MY EYE IN THE SKY”, which described how one of the satellite’s paying customers was the US military, which was purchasing imaging over Iraq.

“From its perch almost 800 km above the Earth,” he opened the article, “an extraordinary seeing-eye satellite they call Radarsat can take a clear picture of your backyard, even in most overcast weather or the blackness of night.” This was more than mere verbal fluff: Weston apparently believed that the satellite really could “perch” in space and keep watch on a ground target.

But the next paragraph has the stunner: “Radarsat is one of ours, built with $450 million of pure Canadian tax money… [It] is also likely to become one of Canada’s key contributions to George W. Bush’s missile defence program. That would be the same missile defence program [the Canadian government] absolutely, without a doubt, swears Canada has not joined.”

Weston doesn’t like this. “In one way,” he admitted, “using the extraordinary capabilities of Radarsat to help defend the continent carries some practical logic. On the other hand, making it a part of the George Bush military machine utterly offends its intended peaceful mission as Canada’s contribution to defending the environment.”

Earlier this month, Weston returned to this theme in another article. “Canada has an extraordinary seeing-eye satellite called Radarsat that would fit very nicely into the Bush missile defence system for North America,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, a quick search on the Internet for Radarsat revealed the breadth (and shallowness) of the “weapon” smear.

| “Canada has an extraordinary seeing-eye satellite called Radarsat that would fit very nicely into the Bush missile defence system for North America,” Weston recently wrote. |

Richard Sanders, coordinator of the Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT) and editor of “Press for Conversion!”, wrote, “Although RADARSAT is commercial, it is probably Canada’s single-most important technological contribution to U.S. war efforts”. Sanders went on: “In February 2005, Canada’s government made a hollow and meaningless proclamation to the effect that it would not participate in BMD [ballistic missile defense]. This has been repeated ad nauseum by an unquestioning and thoroughly compliant media.”

Regarding Radarsat-2, he added : “Unique technology aboard this space-based radar was developed by Canadian scientists in collaboration with America’s Ballistic Missile Defense Organization. Top US warfighters consider it the ‘Holy Grail’ for future Theatre BMD applications and anxiously await using its targeting functions in pre-emptive, first-strike attacks against alleged missile sites.”

In August 2006, commentator Daniel Workman wrote: “NATO and U.S. warfighters are counting the hours before they can add RADARSAT-2’s space-based radar system to their arsenals, particularly its Ground Moving Target Indication (GMTI) capability. GMTI is being groomed for use in gathering target data for first-strike attacks during missile defense engagements. Using RADARSAT-2, armed forces can locate enemy positions on the battlefield and share information and images with coalition allies. In the current Middle East crisis GMTI could provide a 24/7 surveillance tool to search for and destroy Hezbollah's elusive missile launchers from the relatively safe confines of space.” Workman clearly believes that the satellite can perch in space over a target continuously (“24/7”), a delusion that seems to be widely shared.

Confronting the accusers

For technical issues of space operations, I found the allegations impossible to believe. The satellite’s low orbit, I knew, placed it over any particular missile base for only a few minutes each day, if that. As a ground survey sensor (Radarsat-2 has a moving target indicator that can detect vehicles crossing the surface), I doubted it could detect missiles in flight. And as a “store-dump” communications system, I could see no way it could report any such sightings in real time, even if it could make them.

So I emailed Weston, the journalist responsible for the most widely published versions of the claim, asking for backup technical data. The conversation was enormously illuminating—but not about Radarsat. The full text will be on my home page but here is a summation.

On Sunday, June 3, at 9:07 PM, I asked him for “any objective reason to defend this statement”, or was it just his intuition or imagination? The following morning, at 8:59 AM [all times CDT], Weston replied. “Thanks for your note. Of course, you are absolutely right -- I have spent the past 35 years in journalism making stuff up and throwing around insinuations just for fun.” He then accused me of “arrogance and condescension”, but provided no citations to back up his claim about Radarsat.

My reply at 10:13 AM urged him to answer: “Let's talk about what I asked about, the technical issues.” Five minutes later he sent me a copy of the December 2004 article, with comments: “Here's something else I made up in Dec. 2004.” He defended its accuracy by writing that he had received no skeptical feedback before. The article described using Radarsat to periodically monitor the status of potential military targets but nothing about missile defense.

After reading it, I replied at 12:12 PM: “How, exactly, do you imagine that it function in that [missile defense] role? Do you imagine its radar will track incoming missiles? If so, how?” He immediately emailed back. “Now you are getting into the technical details of MDS, Radarsat II, and what the two countries have in mind for both. For that, I have relied on my sources in the Canadian government.” He was not willing to share those sources, he added.

I was beginning to suspect that Weston had no idea how Radarsat was supposed to actually work. So all of my own initial doubts about the accusation would never have occurred to him. He didn’t know enough to realize how little he knew, I began to think.

| Radarsat is a tool that shouldn’t be messed around with by poisoning the atmosphere surrounding its abilities and purpose. |

At 2:20 PM I replied at length with new questions about what basic capabilities Radarsat had that would be needed for a role in a missile defense system: dwell time, detection capability, and real-time reporting capability. Without such understanding, I doubted he knew enough to judge the validity of the incendiary claim he was publicizing, and I told him so: “If you haven't asked your sources such questions, maybe you didn't dig deep enough.”

I had pretty well by then decided that he really didn’t know what he was writing about, but would never admit it. His reply tended to confirm that suspicion. At 5:41 PM, his next (and last) message was of further aggrievement over more perceived personal insults. “I honestly have better things to do than justify myself to you. Have fun being superior. If I need a lesson in journalism, I'll be sure to call.”

There was no further communication from him. But by that time, I was already in touch with the Canadian Space Agency’s Media Relations office. Julie Simard, a communications advisor in that office, sent me a detailed statement.

“RADARSAT is not linked with the ballistic missile defense [BMD],” she flatly declared. “It is intended to observe the surface of the Earth.”

The difference, she continued, is that “BMD satellites observe missiles in flight or on trajectories above the Earth. Remote sensing satellites do not.” This was as I had initially suspected.

Aside from the physical impossibility of perching over an enemy missile base, or in relaying any sudden “blips” back to a command center, Simard added another technical feature that on its own made such a weapons application impossible: “It takes more than 29 hours to program RADARSAT for images acquisition, it is therefore impossible to send real-time signal back.”

On June 8, in response to my request for more detailed specifications, Simard sent another informative message. “RADARSAT-1 and RADARSAT-2 have no ‘continuous communication’ with ground reception facilities. Both R-1 and R-2 are NOT linked through a communication relay satellite.” Instead, they talk via Canadian facilities, but can downlink data to small remote terminals as commanded from Canada.

Having given up on Weston, I sent similar queries to the authors of the two website articles quoted above. Both responded promptly, constructively and graciously. We were prepared to disagree about interpretations and recommendations, but not, it was clear, about reality.

Sanders responded that while he knew the satellite could not perch over a ground target (as Weston had written), and that it could not track missiles in flight, he believed that it could be quickly reprogrammed and could communicate continuously with its control center.

He elaborated: “The link between RADARSAT 2 and [Theatre Missile Defense] is [Ground Moving Target Indicator]. NATO has conducted TMD exercises using RADARSAT.” This is an intriguing and plausible concept if the purpose is to locate enemy mobile short-range missile batteries, and strike them before they can launch. It is an entirely legal activity never covered by the ABM treaty and one that dozens of countries are interested in—but it is not part of a national missile defense system (the “Bush plan” as Weston calls it).

In his separate reply, Workman explained (June 8) why he thought the communications link was continuous: “Documentation published in 2001 states that RADARSAT can provide an uninterrupted stream of Earth-observation data from space used for such applications as detecting and monitoring ships on the ocean.” When confronted with Simard’s reply, he responded: “My information is from a Canadian shareowner magazine that uses the words uninterrupted data acquisition. Granted the authors are freelance writers, and not scientists.” Upon further discussion, he accepted Simard’s information, and concluded: “Thanks for sharing your insights. I've deleted the misleading statements.”

Do such ravings such as Weston’s threaten any harm? Quite possibly. Anything that diminishes the clarity of the world’s appreciation for space assets such as Radarsat, or raises distrust (even active hostility) among significant portions of the population, might result in damages ranging from less-than-optimum exploitation of its capabilities all the way to active measures to interfere in those operations.

In November 2005, as Radarsat-1 was marking its tenth anniversary in space, the soon-to-retire head of the Canadian Space Agency Marc Garneau (Canada’s first astronaut) issued a celebratory statement: “Canadians can be proud. RADARSAT is more than just a satellite—it is a humanitarian service that Canada provides to its communities… and to the world. It is Canada’s ‘eye in the sky’ that monitors our land and seas, helps us manage our natural resources and assists those in need when disasters strike.” This is a tool that shouldn’t be messed around with by poisoning the atmosphere surrounding its abilities and purpose.