Sputnik’s blastoff: the terrifying view from the launch siteby James Oberg

|

| For orbital mechanical reasons that only later became “obvious,” what these observers saw convinced them for several desperate minutes that the launch was failing. |

The satellite itself was never brighter than 4th or 5th magnitude. Some instrument equipped observers in America’s “Moonwatch” program logged sightings of Sputnik, and a few private observers with binoculars and accurate visibility predictions spotted the tiny moving dot among the stars. However, what most people, including myself, observed was Sputnik’s massive carrier rocket. This boxcar-sized behemoth flashed as it tumbled end over end. During its three-month space voyage, it got as bright as a 1st-magnitude star.

The first Sputnik presented an entirely different visual apparition to those who witnessed it actually taking off. Workers at the launch site near the Aral Sea in central Asia watched it soar into space during its near-midnight launch. For orbital mechanical reasons that only later became “obvious,” what these observers saw convinced them for several desperate minutes that the launch was failing.

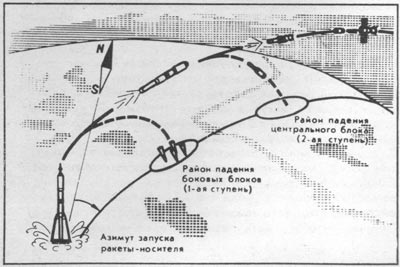

During the previous months’ test flights of the R-7 (“Semyorka”) intercontinental ballistic missile, ground observers had seen the multi-flamed rocket soar high into the sky, then arc to the northeast as it continued to climb. The trajectory was “lofted,” thrown at a high angle to peak about 1,000 kilometers high, halfway to its impact point.

On later flights, which worked, the engines faded with growing distance while still high in the sky, probably halfway to the zenith. But for earlier flights, seared into the fresh memories of the witnesses, the light in the sky flared and then fell back toward the horizon as the engines exploded and burned. Just as with shot-down warplanes of the still-recent “Great Patriotic War” (aka World War 2), of which most space workers were veterans, a flame falling toward the horizon was a doomed craft.

Then, on October 4th, as the Sputnik rocket climbed higher and higher, these observers watched, wondered, and then worried as its angular motion across the sky soon took a frightening downward turn. According to witnesses who later recalled the event, the handful of trajectory specialists watching from an observation point a mile away tried to console their distraught colleagues and clarify what they were actually seeing. An orbital flight was not lofted to a peak altitude, as the surface-to-surface launches had been, so of course the motion across the sky would be very different.

Instead, in order to achieve orbital velocity as efficiently as possible, the rocket would change to a horizontal flight path as soon as it was above most of the atmosphere. Once it gained enough velocity in that lower orbit, it would successfully “fall over the receding horizon” and remain in Earth orbit.

| With later experience, the view that had so anguished the eyewitnesses to the birth of the very first artificial satellite became understood as a “normal” feature of how spaceflight should look to human eyes and brains. |

Only rockets aimed to fall back to Earth, as the long-range bombardment missiles were, counter-intuitively appear to fade away and disappear as they soar upward. Conversely, in the new common sense of the minutes-old Space Age, rockets not intended to fall back to Earth appear, instead, to head downward towards the far horizon.

The impression that Sputnik was falling back to Earth was an illusion of perspective. Ground observers saw it moving away from them horizontally in its 296-second thrust into orbit. True, the Sputnik rocket’s dimming flame was getting lower in the observers’ sky, but this was due only to the growing distance: the rocket was not losing altitude, but was concentrating almost entirely on gaining speed.

The launch was succeeding, and it did succeed. With later experience, the view that had so anguished the eyewitnesses to the birth of the very first artificial satellite became understood as a “normal” feature of how spaceflight should look to human eyes and brains. Spaceflight had begun its immense influence on changing human perspective on so very many things.