Red planet scareby Jeff Foust

|

| “They’re going to be landing humans on the Moon,” Nelson said of China. “That should tell us something about our need to get off our duff and get our Human Landing System program going vigorously.” |

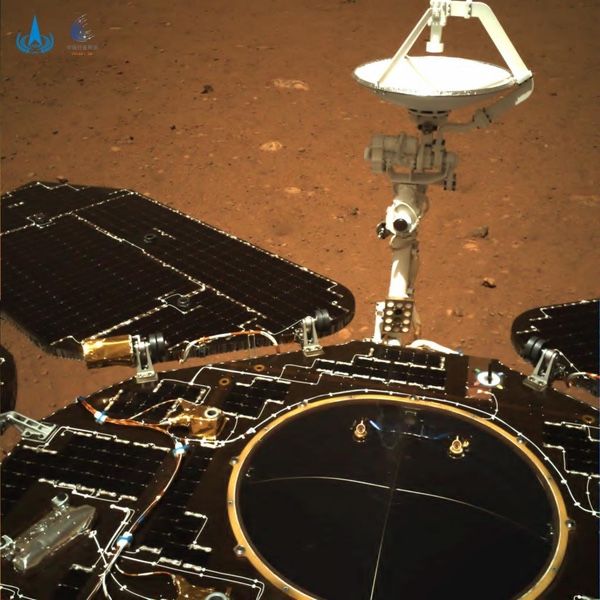

“Congratulations to the China National Space Administration on receiving the first images from the Zhurong Mars rover!” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement Wednesday, when the Chinese space agency released the first images from the rover, at the time still on top of its landing platform. (The rover rolled down a ramp onto the surface Friday night.) “As the international scientific community of robotic explorers on Mars grows, the United States and the world look forward to the discoveries Zhurong will make to advance humanity’s knowledge of the Red Planet.”

But even as Nelson was congratulating China for the successful landing, he was using it to warn Congress about Chinese space intentions more broadly. “It is a very aggressive competitor,” he said of China during a hearing of a House appropriations subcommittee on NASA’s budget. “They’re going to be landing humans on the Moon. That should tell us something about our need to get off our duff and get our Human Landing System program going vigorously.”

On two occasions during the two-hour hearing, which took place at the same time that NASA released Nelson’s congratulatory statement, Nelson brandished one of the images of Zhurong, showing the rover and the Martian terrain. “I want you to see this photograph,” he said at one point during the virtual hearing, holding up the printout of the image to the webcam in his office at NASA headquarters. “I think that’s now adding a new element as to whether or not we want to get serious and get a lot of activity going in landing humans back on the surface of the Moon.”

NASA administrator Bill Nelson holds up an image from the Zhurong rover to make a point about China’s space capabilities at a May 19 House appropriations hearing. (credit: House Appropriations Committee) |

The link between a Mars rover and human missions to the Moon was a little tenuous, but Nelson seemed to be making the case that if China could land a rover on Mars, it could to something more sophisticated at the Moon. China, of course, has landed three spacecraft on the Moon, including the Chang’e-5 sample return mission late last year.

China has three more robotic lunar lander missions planned in the next several years, Nelson said, and claimed that studies showed it was planning “a flyby and a lunar lander in the decade of the 2020s.” Since China has already done robotic lunar landers and orbiters, the implication was that these would be crewed missions, even though China has not announced any firm plans for human missions beyond the space station it is starting to assemble in low Earth orbit.

Nelson used China’s Mars landing accomplishment, and claims of lunar plans, to argue for more funding for NASA’s own Artemis program. He revealed that NASA asked Congress to include $5.4 billion in a proposed infrastructure and jobs bill to support the Human Landing System program, presumably to allow the agency to accelerate the selection of companies for later missions beyond the contract awarded (and under protest) to SpaceX last month for a single mission. That would be in addition to any funding NASA requests for HLS as part of its fiscal year 2022 budget, full details of which are due to be released later this week.

Less than 24 hours after Nelson’s House hearing, the Senate Commerce Committee met to, among other topics, take up the nomination of former astronaut Pam Melroy to be NASA deputy administrator. Melroy received few questions during the confirmation hearing, with senators backing her nomination. “It’s hard to imagine a more qualified person for this role,” Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA), chair of the committee, said of Melroy.

| “If the United States does not return to the lunar surface significantly before China does, we will not be in a position to lead international partnerships and establish norms and standards of behavior,” Lal warned. |

One committee member, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), did ask Melroy several questions, some revolving around China. He was less concerned about the Mars rover, though, than the launch last month of the first module of China’s space station, a mission that left behind in orbit Long March 5B’s core stage that reentered May 8—harmlessly, but in an uncontrolled fashion—over the Indian Ocean. “How can NASA and our international partners get China to have less of a ‘launch first and ask questions later’ approach and start behaving responsibly in space?” he asked.

“That’s a good question,” Melroy responded. She advocated for developing norms of behavior, like orbital debris mitigation guidelines. “We also need to call China out, as Administrator Nelson did, when they violate those norms.”

That was a reference to a statement by Nelson immediately after the Long March 5B reentry. “It is clear that China is failing to meet responsible standards regarding their space debris,” Nelson said in the statement. “It is critical that China and all spacefaring nations and commercial entities act responsibly and transparently in space to ensure the safety, stability, security, and long-term sustainability of outer space activities.”

Those comments about the rocket reentry and the Mars rover suggest that NASA leadership plans to play up competition—or, at least, perceived competition—with China as a means of winning support for its own programs.

“The first nation to operate regular crewed missions on the Moon will set the norms and standards that other nations will be pressured to follow,” Bhavya Lal, senior advisor for budget and finance at NASA, said in a May 11 presentation at a meeting of the Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium.

NASA has proposed setting up those norms and standards for lunar missions through the Artemis Accords, which the US and eight other countries have signed on to (South Korea announced last week it planned to join the Accords as well.) But, she suggested, if the US faltered in some way, it will be China that sets those norms and standards.

“If the United States does not return to the lunar surface significantly before China does, we will not be in a position to lead international partnerships and establish norms and standards of behavior in deep space that are aligned with US and democratic values,” she warned.

“China would be happy to craft the rules and norms of deep space, with Russian participation,” Lal continued, referring to a partnership between the two countries on an international lunar research base some time in the 2030s. “Many countries in the world, including our European partners, would be eager to work with the Chinese as its plans unfold.”

“The United States going back to the Moon as part of the Artemis program, along with the associated Artemis Accords with our international partners, will improve US efforts to counter China’s course of influence in cislunar space, as China tries to cast and recast international rules, norms, standards, and institutions,” she concluded.

Such comments, about Zhurong and China in general, make clear that the Biden Administration has little interest in a rapprochement with China in space. NASA’s cooperation with China is hindered by a provision in federal law called the Wolf Amendment, which places restrictions on bilateral cooperation between NASA and Chinese entities.

| “China has made their goals very clear, to take away space superiority from the United States. We are right to be concerned,” Melroy said. |

Some in the space industry who advocated for loosening those restrictions (see “Defanging the Wolf Amendment”, The Space Review, June 3, 2019) hoped that the Biden Administration might be open to doing so. But the specter of a US-China space race to the Moon (or Mars) seems to have quashed any chances of doing that.

Cruz, at the Senate confirmation hearing, asked Melroy about the Wolf Amendment. “What are your thoughts about China’s growing power in space, and does it concern you? Do you think that the guardrails of the Wolf Amendment are adequate to protect US space technology and our global competitive advantage in space and space exploration?” he asked.

“You are right to be concerned,” Melroy responded. “It’s not just the landing on Mars, which is very impressive, but also a couple of landings on the Moon, and the construction starting of a low Earth orbit space station. China has made their goals very clear, to take away space superiority from the United States. We are right to be concerned.”

“I support the Wolf Amendment, as it’s called. It’s the law. NASA will continue to follow the law,” she said.

She added, though, that NASA should have the ability to talk with China on some issues, such as space safety and space traffic management. “We have to operate together in the space domain, so there are times where it’s in the best interest of the United States to talk to China.”

Melroy offered a different assessment, though, last year. “Trying to exclude them I think is a failing strategy,” she said of China in an interview with Politico. “It’s very important that we engage.”

While NASA may think that a prospect of a US-China space race will spur members of Congress to fund the Artemis program and Mars exploration, those claims could also be used as a cudgel against other agency plans. On Friday, Reps. Frank Lucas (R-OK) and Brian Babin (R-TX), the ranking members of the full House Science Committee and its space subcommittee respectively, wrote to Nelson about the agency’s recent announcement it would postpone the next competition in its New Frontiers program of medium-class planetary science missions by two years, citing funding issues.

Lucan and Babin questioned that delay in light of plans by NASA to seek an increase in funding for Earth science programs in its fiscal year 2022 budget proposal. They also used the Zhurong landing to argue for more funding for planetary programs—presumably at the expense of Earth science or other agency programs.

“China’s accomplishment and the Biden Administration’s retreat from planetary science exploration present a stark contrast today,” they wrote. “Delays and cuts to planetary science exploration could have particularly dire impacts on U.S. leadership in space as China seeks to expand its planetary science program, pursue international partnerships to expand its influence, and justify the Communist Party’s control over the Chinese people through scientific accomplishments.”

All that rhetoric, though, depends on what China actually plans to do in space. The same day that Nelson spoke before the House appropriators, Yao Jianting, deputy general secretary of the China National Space Administration, appeared at a space conference organized by Britain’s Royal Aeronautical Society, giving an overview of Chinese space activities, including the Zhurong landing and development of a Chinese space station.

Yao, though, didn’t discuss any human spaceflight activities beyond the development and use of that space station, and the only future lunar missions he mentioned are the three robotic landing missions as well as the ill-defined international lunar research base. As for Mars, the only mission on his timeline was a sample return mission, scheduled for no earlier than 2028. Zhurong, it seems, is not going to have many new visitors for a while.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.