A shifting balance of space cooperation?by Jeff Foust

|

| “What I hope is that they’re going to think long and hard before they would pull out of the cooperation that they have had with us,” Nelson said of Russia. |

Now that partnership is changing—or, at least, the Russians want people to think it’s changing. In recent months, Russian officials, including Roscosmos director general Dmitry Rogozin, have suggested that they could drop out of the International Space Station program as soon as the middle of the decade in favor of pursing their own national space station, a move that would jeopardize the future of the ISS. At the same time, Russia has played up cooperation with China on lunar exploration, including, ultimately human missions. But rhetoric and reality are not always in agreement.

The future of Russia on the ISS

In April, Russian officials, including Rogozin as well as deputy prime minister Yuri Borisov, stated they were reconsidering long-term participation in the ISS. Borisov went so far as to suggest that Russia would withdraw from the partnership in 2025. Their argument was that aging ISS was becoming more difficult and expensive to maintain, such as persistent small air leaks in the Zvezda module.

Russian officials have also talked about developing its own space station around that time. That station, they argued, would be more useful than the ISS in part because it would be in a different orbit: sun-synchronous, rather than the ISS’s 51-degree orbit, enabling it to observe parts of Russia not easily visible from the ISS. (Presumably, though, Earth observation satellites would be more cost effective than a crewed station for that role.)

The announcements came during an interregnum at NASA in the early months of the Biden Administration, with the White House’s choice for NASA administrator, Bill Nelson, nominated but not yet confirmed. Asked about Borisov and Rogozin’s comments shortly before the Crew-2 launch, acting NASA administrator Steve Jurczyk emphasized the good relations NASA and Roscosmos had.

“We still have a very, very, really strong relationship with Roscosmos and Russia on ISS,” he said, adding that he hadn’t had any formal discussions with his Russian counterparts on the future of the station. “They’ll do their work and decide what they want to do and we’ll make our decisions on our side with our partners.”

Nelson, who has emphasized competition with the Chinese in his first weeks in office (see “Red planet scare”, The Space Review, May 24, 2021), played down any rift with Russia, instead emphasizing the cooperation that dates back a half-century to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project—to the point to referring to the “Soviet” rather than “Russian” space program.

“You are hearing statements out of the Soviet government and Soviet space program—Russian space program, saying that they’re going to pull out of the space station,” he said, correcting himself in a briefing with reporters after his “State of NASA” address June 2. “What I hope is that they’re going to think long and hard before they would pull out of the cooperation that they have had with us.”

“My experience in government is that politics kind of gets in the way,” Nelson, the former senator, added. “But the people on the line that are doing the work have different thoughts. I suspect that most of the people in the Russian space program really enjoy working with the Americans.”

Kathy Lueders, NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration and operations, noted that Roscosmos is still planning to launch a new ISS module, the Nauka multipurpose lab module, in July. (That module has suffered years of delays because of extensive technical problems.) “Launching a new module and activating it is not a sign of pulling out of the relationship,” she said.

| “We are discussing this particular issue with him,” Rogozin said of Nelson and the future of the ISS. “It’s a complicated issue.” |

Nelson and Rogozin had yet to speak at the time of those comments but talked by phone two days later. Afterwards, NASA released a perfunctory statement, with Nelson describing a “productive discussion” with Rogozin about the ISS in particular. “NASA is committed to continuing that very effective ISS partnership,” he said.

Roscosmos issued a slightly longer statement, which included some airing of grievances. Rogozin complained, according to the statement, about sanctions levied by the US government “against the enterprises of the Russian space industry, as well as the absence of any official information in Roscosmos from the US partners on the plans to further control and operate the ISS.” Those issues, he said, were “substantially hindering the cooperation” between the two agencies.

The two met again, also virtually, last week during the Global Space Exploration Conference, or GLEX 2021, by the International Astronautical Federation. While the conference was an in-person event in St. Petersburg, Russia, many Western space agency officials stayed home, participating in panel sessions and other meetings online.

Nelson, appearing on the same heads-of-agencies panel as Rogozin June 15, again backed a long-term future of the ISS. “The ISS is a good example of international cooperation and the incredible science that we can accomplish when we work together,” he said. He added that he continues to push for a formal extension of ISS operations to 2030 and expects that Congress, after several attempts, will pass legislation formally authorizing NASA to do so this year.

“We are discussing this particular issue with him,” Rogozin said immediately after Nelson on the panel. “It’s a complicated issue because, on the one hand, this is not a new station. It costs quite a lot to maintain and develop it.”

“On the other hand, this is the biggest and most sophisticated human-made structure,” he continued, likening it to a “flying football stadium.” Rogozin said he hoped to find “a joint solution” to the future of the ISS.

At a press conference later in the day, Rogozin said he and Nelson talked again after the panel. They agreed to meet in person the fall, Rogozin said—possibly at the International Astronautical Congress in late October in Dubai—and that Nelson would also come to Russia. (Sanctions dating back to Rogozin’s role as deputy prime minister in the annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine in 2014 prevent him from visiting the US.)

That discussion also revisited the future of the ISS, including an extension to 2030. “Generally speaking, we are not against this option, but this would require a lot of work in terms of establishing whether the station is fit: whether it will physically survive to 2030,” he said.

Nelson, testifying that afternoon before a Senate appropriations subcommittee, also mentioned his latest meeting with Rogozin while discussing his desire to extend the ISS to 2030. “He was very bullish about cooperation,” he said of Rogozin.

Nelson brought up an interview Russian president Vladimir Putin gave to NBC News where he appeared to endorse continued cooperation between Russia and the US. “I think you just misunderstood the head of the Russian space program,” Putin said in that interview about claims Roscosmos wanted to end the ISS as soon as 2025. “We are interested in continuing to work with the US in this direction, and we will continue to do so if our US partners don’t refuse to do that.”

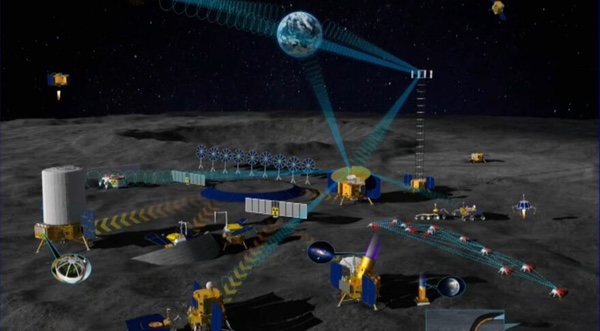

China and Russia released this concept of the International Lunar Research Station they propose to develop over the next 15 years. (credit: CNSA/Roscosmos) |

A Chinese-Russian lunar base… eventually

At the Senate hearing, Nelson warned again of a “very aggressive” China when it comes to space exploration, this time working in cooperation with Russia.

“I think you’re seeing statements being made by the Chinese government that they don’t want to wait around until the 2030s to land on the Moon with humans,” he said, not citing any specific statements to that effect by the Chinese government.

“And tomorrow, at this global conference in St. Petersburg, Russia, we are expecting a statement being made jointly by China and Russia as to what their plans are. Let’s see what that is,” he said.

| “I think you’re seeing statements being made by the Chinese government that they don’t want to wait around until the 2030s to land on the Moon with humans,” Nelson said. |

Nelson was referring to a session of GLEX 2021 where Chinese and Russian officials promised to provide an update on their proposed International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) that they would jointly develop, along with perhaps other international partners, on the Moon.

That session June 16 did include Chinese officials (who, like their Western counterparts, were participating virtually) with Russian counterparts in St. Petersburg. In the hour-long sessions, they talked through their plans for the ILRS.

Those plans were both grandiose and underwhelming. Wu Yanhua, deputy head of the China National Space Administration, outlined a three-phase approach to develop the ILRS. The first phase would use a series of robotic missions already planned by China and Russia, including landers that will go to the south pole of the Moon over the next several years.

A second phase, running from 2026 through 2035, would gradually build up infrastructure at the south pole, including power and communications as well as research facilities, using missions dedicated to the ILRS rather than previously planned landers. Only in the third phase, starting in 2036, would the ILRS enter its “utilization” stage, one that would include crewed missions.

While the establishment of a crewed lunar base is ambitious, the roadmap only provided modest additional details about the proposed station. The announcement offered nothing about costs or how the work would be shared among China, Russia, and any international partners. Much of the announcement was describing in detail the various roles international partners could take, right down to contact information for relevant Chinese and Russian officials.

At the GLEX 2021 press conference the day before, Rogozin declined to identify any specific prospective partners Russia and China had been in discussions with about the ILRS. However, he did mention one desired partner: “I think, suffice it to say, that our key prospective partner in relation to this project is the European Space Agency.”

That appears to be more aspirational than anything else at this stage. Asked about Rogozin’s comments at an ESA press conference just hours after the ILRS session at GLEX 2021, Josef Aschbacher, ESA’s director general, said basically the agency only had received an invitation to participate.

“I got a letter of invitation to join the International Lunar Research Station, both co-signed by Mr. Rogozin and the head of the China National Space Administration,” he said. “The offer is on the table. We will reflect with our member states how to respond. I’m not in a position today to give an answer.”

| And humans to the Moon? “We are still focusing on unmanned lunar exploration as the priority of our work in the near decade,” Wu said. |

And, for all the talk by Nelson of China’s “very aggressive” space exploration program and a desire to speed up landing Chinese astronauts on the Moon, the event gave no sign China was in a hurry. An audience question during the roadmap session directly asked when the countries were planning to land humans on the Moon.

Wu, in his response, mentioned the launch of the core module of China’s new space station. (Shenzhou-12, China’s first crewed mission since 2016, launched to that module a little more than 12 hours after the GLEX 2021 roadmap session.) “We are focusing on the Tianhe core module” and the rest of the station, he said. “This is the priority of our work currently.”

And humans to the Moon? “We are still focusing on unmanned lunar exploration as the priority of our work in the near decade,” he said. “So, we hope we are able to actually send our researchers to the surface of the Moon in the future to carry out missions on the surface of the Moon.” He offered no date more specific, or earlier, than the post-2035 phase of the ILRS given in the presentation.

Perhaps in a decade or two we will look back and see these events as the beginning of a great realignment in space cooperation, with Russia moving away from its longstanding cooperation with the West in human spaceflight and closer to China. But for now, there’s not much different in NASA’s relationship with Russia, or Russia’s relationship with China.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.