War at sea, seen from aboveby Dwayne Day

|

The Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano sinking on May 2, 1982, after being struck by a torpedo fired by a Royal Navy submarine. After the sinking, the Argentine government claimed that American “spy satellites” provided the British with the ship’’s position, which the United States denied. |

Tiny little islands

In early April of 1982, Argentine forces invaded the small, sleepy, sheep-filled archipelago known as the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic, which Argentina refers to as the Malvinas. Very quickly, British forces mobilized in response to retake the islands. Royal Navy warships sailed from ports in the United Kingdom only a few days after the invasion, but it took them several weeks to arrive at the cold, wind-swept islands. After that, the war became a bloody slugfest. The Argentines suffered 649 killed, including 323 men lost when the cruiser General Belgrano—a former US Navy warship—was sunk by a British submarine, and Great Britain suffered 258 of its soldiers, sailors, and marines killed. The Royal Navy lost two destroyers, two frigates, and three other vessels to Argentine Exocet missiles and bombs, including the converted container ship Atlantic Conveyor. As a Royal Navy auxiliary weighing 14,946 gross tons, she technically ranks as the largest naval vessel sunk since World War II, although not a surface combatant like the Belgrano… or the Moskva.

| After the Belgrano sinking, the Argentinians claimed that an American “spy satellite” provided the ship’s location to the British. |

The Reagan Administration initially sought a diplomatic solution to maintain favor with Latin American countries that it was enlisting in opposition to communist influence in Cuba, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. The public American position created the impression, even among some within the British government, that the United States was not helping out its longstanding ally. The reality was that there was extensive cooperation between the US Navy and the Royal Navy. The Americans made available any weapons that the Royal Navy required, essentially opening up the armories and allowing the British to take whatever they needed with the proviso that they would eventually reimburse the United States. That included one hundred of the most advanced version of the American Sidewinder air-to-air missile, to be mounted on Harrier jump jets.

A recent book on the Falklands naval war revealed that an Argentine aircraft carrier and a Royal Navy submarine stalked each other during late April 1982. The carrier eluded attack and spent the rest of the war in port, where it was observed in May by a US reconnaissance satellite. |

Targeting Argentine ships

There were some interesting and unusual revelations about intelligence operations and other covert actions that followed the 30th anniversary of the war. On the British side, one revelation was that the submarine HMS Conqueror, which sank the Argentine navy’s cruiser General Belgrano, later engaged in a highly secret operation to use a form of underwater scissors to cut and grasp a towed sonar array from a Warsaw Pact naval vessel.

The sinking of the Belgrano on May 2, 1982, was one of the most high profile events of the war. But it was not the only time a Royal Navy submarine stalked an Argentine ship. In recent years, more has become known about the cat-and-mouse chase between the Argentine navy’s aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo and another Royal Navy submarine, HMS Splendid. Previously it was thought that the carrier had simply headed to port to sit out the war. But due to the efforts of a diligent Argentine researcher Mariano Sciaroni and his book A Carrier at Risk, we now know that the two vessels came close to detecting and attacking each other on several occasions. Veinticinco had headed toward the Argentine coast after the Belgrano sinking, and Splendid never attained a firing position.

After the Belgrano sinking, the Argentinians claimed that an American “spy satellite” provided the ship’s location to HMS Splendid. A declassified telegram from the US ambassador to Argentina notes that he had been trying to stomp out the claims, which he believed (rightly or wrongly) to be untrue.

In recent years, it has become apparent that throughout the 1970s the United States Navy increasingly used signals intelligence satellites in low Earth orbit for tracking ships at sea. That capability has been known for decades, although the National Reconnaissance Office still has not declassified anything other than the early testing of this capability in the early 1970s (see “Spybirds: POPPY 8 and the dawn of satellite ocean surveillance,” The Space Review, May 10, 2021.) By the early 1980s, the US Navy was seeking to feed satellite ocean surveillance data directly into the missiles of its ships at sea. Details remain classified and it is unknown to what extent this capability was developed by the time of the Falklands War. The Royal Navy may have been able to obtain some data from the American system even if they were not able to fully exploit it (see “Shipkillers: from satellite to shooter at sea,” The Space Review, June 28, 2021.)

| So what was the VORTEX doing for the British? The most likely mission would have been intercepting communications between Argentina’s leadership and military forces within Argentina. |

In 2002, some information was released from Russia indicating that the former Soviet Union had sought to make its own ocean surveillance data available to the Argentinians. The Soviet Union operated a series of signals intelligence satellites as part of a larger program named Legenda, and one of these satellites was launched during the conflict. The Russians claim that information from the satellites allowed them to accurately determine that the British landing force would land on May 21. However, it is unclear from available sources whether the Soviets provided information to the Argentinians, and at least one source indicates that they did, but the Argentinian navy did not make use of the data.

There are other aspects of space and the Falklands conflict that have come to light in more recent years. One that has received increasing attention is the fact that the Argentinian Air Force sought to track the Royal Navy’s fleet as it traveled south by detecting the Doppler shift in satellite signals being sent to the fleet—which itself was practicing strict radio silence.

Secretary of State Alexander Haig with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. In early April 1982, Haig assured the Argentinian president that the United States was not providing the United Kingdom with satellite intelligence. Decades later it was revealed that the United States did provide the United Kingdom with satellite intelligence, although this may have occurred after Haig’s meeting. (credit: US DOD) |

The lion and the VORTEX

The United States did make some of its space intelligence assets available to the United Kingdom. National Reconnaissance Office Director Donald Kerr gave a speech at an NRO town hall meeting in December 2006, and the transcript was later released to GovernmentAttic.org. In a partially censored section of the transcript Kerr referred to the “25th birthday” of a satellite system. The NRO had celebrated this event both at its headquarters near Dulles International Airport in Virginia and at another location, probably an overseas ground site. “It’s extraordinary that this machine born in the analog age is still serving the country in the digital age,” Kerr said. The mission of the satellite is deleted, but Kerr said, “It had to go to war with one of our allies shortly after launch and supported the United Kingdom in the Falklands War. It then came back, in fact to the central Asian theater, and provided notable service there. Now it’s covering the sub-continent India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, still doing significant work. It had a mean mission life of three or four years. Here we are 25 years later and it’s a tribute to the designers and more importantly those that have nursed it along as it displayed all of the symptoms of old age many times over.”

Kerr was undoubtedly referring to a satellite that originally had the code-name VORTEX and was launched atop a Titan IIIC from Cape Canaveral in October 1981. The satellite was controlled from a ground station in England and was placed in a near-geosynchronous orbit, meaning that it could have been shifted from an initial position over the Atlantic Ocean to later cover Asia and eventually India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan (although independent satellite watchers dispute this.) The target for the VORTEX signals intelligence satellites, according to Jeffrey Richelson writing in The U.S. Intelligence Community, was originally Soviet “strategic communications,” meaning communications between missile, bomber, and submarine bases. But several American signals intelligence satellites reportedly entered service focused on one kind of target only to have their operators discover that they could be turned on other kinds of targets as well. The VORTEX satellites were a follow-on to an earlier series of communications intelligence satellites known as CANYON.

Kerr’s comments confirm a story that appeared in a 1997 book written by Mark Urban, UK Eyes Alpha: Inside Story of British Intelligence. Urban wrote:

The Falklands war of 1982 was regarded by most people in the defence and intelligence establishments as a textbook example of Britain’s “special relationship” with the USA in action. The Americans had made certain advanced weapons available to the British and had shared vital intelligence about the location of Argentine ground and naval forces. In Cheltenham, though, there were people who knew that this assistance had sometimes required special pleading. The National Security Agency, GCHQ’s U.S. counterpart, had not achieved global coverage with its sigint satellites by 1982. The craft which was in a position to help Britain monitor Argentine communications was being used by the Reagan administration to eavesdrop on central America, principally El Salvador. One of the GCHQ officers who liaised with NSA recalls, “We had to negotiate very hard to get it moved, and then only for limited periods.” During these spells of a few hours each, the satellite’s listening dish was reorientated towards the south Atlantic in order to help Cheltenham. The NSA did not monitor the downlinked take during these periods, asking GCHQ to alert them if there was anything of U.S. interest in the transmissions.

El Salvador would be an unlikely target for such a satellite considering that the United States already had ground forces in that nation and it seems improbable that a strategic intelligence asset would be focused on rebels operating in the jungle whose communications could be readily intercepted with aircraft and ground-based receivers. If the satellite was indeed focused on the western hemisphere, Cuba and/or Nicaragua were the more likely targets.

In 2015, the State Department produced another in its highly valuable Foreign Relations of the United States series of books. This one focused on the Falkland Islands war and included mention of a discussion that the US Secretary of State Alexander Haig had with Argentine officials in early April. According to a declassified summary: “The Secretary told President Galtieri that the reports that the U.S. has furnished intelligence and satellite information to the UK are untrue. We denied the British request. As a matter of principle we feel that allies should not spy on each other. Our satellite, moreover, was not in a position to collect data from this area. Had it been, we would not have furnished it to the British. He gave President Galtieri his personal guarantee.” The summary is in contrast both to Urban’s 1997 book and Donald Kerr’s 2006 speech, although perhaps the satellite was loaned to the British after Haig had met with the Argentine president. Despite Haig’s assurances to the Argentine dictator, President Ronald Reagan had decided that the United States would fully, if clandestinely, support the United Kingdom in its effort to regain the Falklands.

So what was the VORTEX doing for the British? The most likely mission would have been intercepting communications between Argentina’s leadership and military forces within Argentina, and the most immediate requirement would have been intercepting any communications indicating the launch of aircraft headed toward the Falklands. The Argentines would have had to assume that the British were listening and it would have made sense for them to launch their aircraft while maintaining radio silence. However, in his book, Urban noted that a British source indicated to him that there were limits to just how quiet the Argentines could be; they still had to communicate, after all. The more interesting aspect of Urban’s story is that this event was apparently what prompted the British to develop a signals intelligence satellite of their own, code-named ZIRCON, a plan they later abandoned in favor of paying the United States for access to its satellites.

| It is highly likely that US imagery satellites provided images of Argentine forces and defenses on the islands, as well as targets in Argentina such as airfields and the location of their remaining stockpile of Exocet anti-ship missiles, which were the target of a failed SAS commando raid. |

Whether or not the United States was eager to cooperate, American leaders may have felt required to cooperate at least as far as sharing signals intelligence data was concerned. In 1954, the United States and the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia signed the UKUSA Agreement, also known as the UK-USA Security Agreement, or occasionally the “Secret Treaty.” This agreement obligated the countries to share signals intelligence data, and delineated geographic responsibilities. The United States was responsible for Latin America, most of Asia, Russia, and northern China. Britain is responsible for Africa and the former Soviet Union west of the Urals. Assuming that the VORTEX satellite had initially set up shop over the Atlantic Ocean, it could have been officially used to collect signals intelligence data on Latin America—as required by the agreement—with that data automatically provided to the United Kingdom.

The VORTEX satellite was apparently still working as late as 2009. At the 2009 GEOINT Symposium, Director of the NRO Bruce Carlson mentioned an old spacecraft. “We have a satellite up there that is ten times older than we expected it to be. It has been up there this long [extends his arms out wide] and it has been up there this long [extends his arms out farther] and it’s still working. We expected it to do a mission that had to do with strategic, long-haul communications and today it’s helping us kill bad guys in the AOR [Afghanistan Area of Responsibility]. Now that’s as specific as I can get. But we do that because of the incredible contractor and NRO team that we have that nurses that satellite along and the young people that write software to change its functionality and keep it going.”

Other cooperation

This was probably not the only sharing of intelligence data between the United States and Great Britain during the war. It is highly likely that US imagery satellites provided images of Argentine forces and defenses on the islands, as well as targets in Argentina such as airfields and the location of their remaining stockpile of Exocet anti-ship missiles, which were the target of a failed SAS commando raid. A declassified imagery report from late May indicated that the carrier Veinticinco was in port, with no aircraft on deck. A deleted portion of a declassified documentary on the HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite implies that one of the satellites imaged the Falklands. The seventeenth HEXAGON mission was launched on May 11, 1982, and would have been able to photograph the islands from its polar orbit. However, its first reentry vehicle did not return until June 15, by which time the British had retaken the islands. If American satellite imagery played a role in the conflict, it came from the real-time imagery satellites and not the HEXAGON.

In 2020, John Ferris published Behind the Enigma: The Authorized History of GCHQ, Britain’s Secret Cyber-Intelligence Agency. Unfortunately, the book shed no new light on the intelligence sharing between the two countries. In fact, it omitted some information that had been released by the US government, such as Kerr’s 2006 speech. But in 2020, information was leaked that indicated just how much the United States’ National Security Agency was able to read encryption machines around the world, including those in Argentina. That may have provided significant military information to the NSA, which was then shared with the United Kingdom. It is unknown if American satellites provided the intercepts. Unfortunately, Ferris’ book did not shed much new light on the British ZIRCON signals intelligence satellite.

Other information about the space aspects of the conflict has come to light in more recent years, although not on the operational side but in the realm of US-British relations. In 2021, historian Dr. Aaron Bateman revealed that Britain’s experience during the war highlighted how much the country was dependent upon American intelligence, particularly space, assets (see “The secret history of Britain’s involvement in the Strategic Defense Initiative,” The Space Review, February 1, 2021.) That also may have made British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher more amenable to President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (commonly known as “Star Wars.”) Thatcher believed that to maintain access to American space intelligence collection systems, she needed to support Reagan’s project. She believed that doing so would have other values as well.

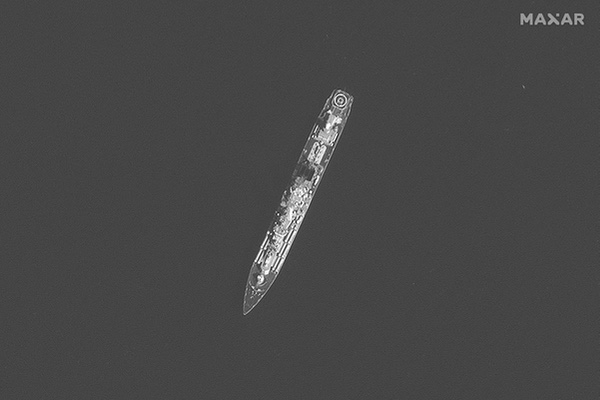

One of the last photos—possibly the last photo—taken of the Russian guided missile cruiser Moskva before the ship was hit by two Ukrainian Neptune missiles. Moskva sank a day after being struck. Commercial satellite imagery like this had been used by open source intelligence analysts to track Moskva’s movements in the weeks before the attack. (credit: Maxar) |

Battle in the Black Sea

The current war in Ukraine, and the saga of the Moskva, highlights just how much has changed in forty years. The United States—and Russia for that matter—has extensive intelligence assets in space. One of the stories of this war is just how much commercial remote sensing has grown, even in only the past few years, and how it has often allowed independent observers to confirm what has been happening on the battlefield, such as the Russian buildup prior to the invasion, and Russian activity and atrocities after the invasion. Open-source intelligence (OSINT) has played an important part in this war, including at sea. Independent naval analysts like H I Sutton have used satellite imagery, including commercial satellite-based synthetic aperture radar technology that was not even available to the military in 1982, to track Russian warships in the Black Sea, including the Moskva.

| Independent naval analysts like H I Sutton have used satellite imagery, including commercial satellite-based synthetic aperture radar technology that was not even available to the military in 1982, to track Russian warships in the Black Sea, including the Moskva. |

Moskva was laid down at the Nikolaev shipyard in Ukraine on the Black Sea in 1976, launched in 1979, and commissioned in 1982. The US intelligence community monitored the development of the ship and his successors (Russian warships are referred to as “he” in Russia.) As of December 1980, while still under construction, the ships had been designated “445-F” by US intelligence analysts, and the lead ship was then expected to enter sea trials by the end of 1981, as eventually happened. The ship was initially designated BLACKCOM 1 (for Black Sea Combatant), and then when observed at sea with the name Slava, NATO designated them the Slava-class.

The Slava-class cruisers were equipped with a formidable arsenal of anti-ship missiles intended to attack American aircraft carriers. But with the decline of the Russian Navy after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the three operational ships spent much time at port. They often served as flagships, with the Slava—renamed Moskva—serving as the Russian Navy’s Black Sea flagship.

A week before the Moskva sinking, in an April 7 article, H I Sutton, with the help of independent analyst Damien Symon and others, noted that Moskva was following a rather predictable pattern. If they noticed that based upon publicly available information, it’s not hard to believe that Ukrainian coastal defense forces did as well. On the evening of April 13, Moskva was struck by two Ukrainian Neptune missiles launched from a coastal battery. Based upon images taken by a sailor on one of the rescue vessels, the missiles struck the cruiser port amidships, causing extensive fires. The crew apparently abandoned ship, although it is unknown how much they fought to save the Moskva before taking to the life rafts. Russian statements on the war, and what happened to the ship, have zero credibility—for example, after the Russian government stated that the ship had been lost in a storm while being towed to port, photos of the burning ship being assisted by tugs showed calm seas.

As Sutton has noted, one of the last images taken of the Moskva was by a Maxar commercial satellite. After the cruiser was hit and rescue ships rushed to its aid, on April 13 a commercial synthetic aperture radar satellite imaged the cruiser and several smaller ships surrounding it. Sutton shared that image to Twitter and, days later, a merchant sailor’s cellphone images and video of the ship depicted the same scene, although this time from sea level. Since that time, Sutton has been using satellite imagery to detect any salvage operation, and new imagery may depict an oil slick at the site of the wreck.

European Sentinel satellite image from late March. A Russian Alligator-class ship is burning at dockside at upper right. Two Russian Ropucha-class landing ships fled after the initial explosions and had fires on their decks due to exploding debris. Somebody who downloaded the image off the Sentinel website noticed a ship at lower left doing many circles, as if it was suffering a mechanical malfunction. This may be one of the damaged Ropucha-class ships. |

The images of the Moskva are not the only examples of satellite imagery showing the naval aspects of the Ukraine war. After a Russian Alligator-class amphibious landing ship blew up at dockside in late March, satellite imagery showed the destroyed vessel sunk alongside its dock. Web camera footage had previously shown the ship on fire and two other Russian vessels rapidly moving away, both of them also on fire, apparently from debris that landed on their decks. Shortly thereafter, a European Sentinel satellite image of the area was downloaded from the Sentinel website and circulated on the Internet. It not only showed the ship burning at dockside, but also a very curious event taking place out in the Black Sea—a vessel circling repeatedly, as if it had suffered a mechanical failure. This was apparently one of the two damaged ships that had fled the port, obviously in some distress.

| Open-source analysts have insight and determination, as well as the Internet, which enables rapid sharing of information. Unlike 40 years ago, we can now watch the war as it unfolds. |

Open-source intelligence analysts like Sutton and others have some incredibly powerful tools available to them, often at no cost. Space-based synthetic aperture radar was not even available to the United States in the early 1980s, yet the data is publicly posted today not long after it is sent to a ground station. Today’s commercial imaging satellites are not as good as American military systems in the early 1980s in terms of resolution (a function of the camera system’s aperture), but they are plentiful, and a lot of their data is made freely available.

But open-source analysts can only use the data that is, by definition, public. Not only do they lack access to more powerful military satellites, they don’t have access to data produced by many of the same satellites that is not released. They also do not have access to signals intelligence data that can be used to track ships at sea by their radar and radio emissions (although in Ukraine’s ground war, the Russians have often used unencrypted communications that have been intercepted even by amateur radio operators). Open-source analysts also lack powerful processing tools that can merge data from multiple sources and geolocate targets. What they do have, however, is insight, and determination, as well as the Internet, which enables rapid sharing of information. Unlike 40 years ago, we can now watch the war as it unfolds. From the ground, the sea, and above.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.