NASA-SpaceX study opens final chapter for Hubble Space Telescope.by Christopher Gainor

|

| Prior to the September 29 announcement, the ultimate fate of Hubble was something of a mystery. |

The two space telescopes are different from each other in more than age, however. JWST operates in infrared wavelengths while HST gathers data in ultraviolet, visible, and near infrared wavelengths. Because they complement each other, many scientists have been looking forward to joint operations involving Webb and Hubble, along with continued observations by HST and new data from JWST.

On September 29, NASA and the European Space Agency released images taken by both space telescopes of the impact of the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft on the asteroid Dimorphos three days earlier. Later that day, NASA had some major news about the future of Hubble at a telephone press conference called on short notice.

NASA and SpaceX announced that they had signed a Space Act Agreement a week earlier to study the feasibility of an idea from SpaceX and the Polaris Program, a private initiative promoting private spaceflight, to boost Hubble into a higher orbit with SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft. There will be no cost to the US government for this six-month study, and no commitments on any actions to follow that study.

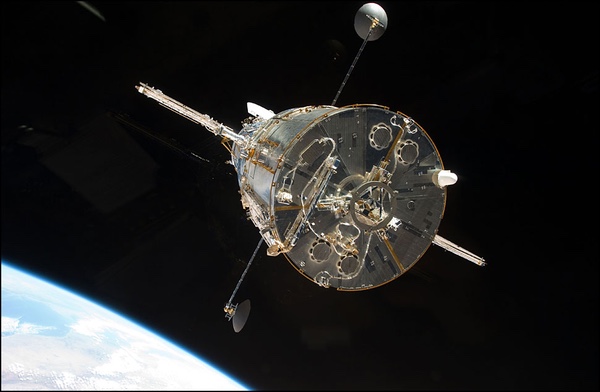

Since the last of the five shuttle servicing missions visited Hubble 13 years ago in 2009 and boosted its orbit to an altitude of 565 kilometers, HST’s orbit has fallen to 535 kilometers. Without another boost, Hubble will continue to descend, with reentry into Earth’s atmosphere estimated to take place around 2037, 15 years from now.

Prior to the September 29 announcement, the ultimate fate of Hubble was something of a mystery. Whenever questions have been asked about the ultimate disposition of the 11,000-kilogram HST, NASA officials have replied that it is the policy of the United States government that Hubble not make an uncontrolled reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere. But they have never spelled out how that policy would be fulfilled.

| Any mission designed to boost Hubble into a higher orbit inevitably raises the question of servicing and updating Hubble. |

On the final Hubble servicing mission in 2009, the crew of Atlantis installed a grapple fixture to the bottom of the school-bus-sized HST. It has been widely assumed that a robotic propulsion module would eventually attach itself to the grapple fixture and then send Hubble either to a controlled reentry ending in a deserted part of the South Pacific, or possibly to a much higher graveyard orbit. Even today, no appropriate propulsion module exists.

One sign that this assumption was not universally shared came in 2020, when astronomer and former shuttle astronaut John Grunsfeld called for consideration of a servicing mission to HST using a crewed Orion spacecraft (see “Hugging Hubble longer”, The Space Review, June 15,2020).

Now NASA and SpaceX will study the idea of using a Dragon spacecraft, not necessarily crewed, to raise HST’s orbit and nothing more. The third partner in this enterprise is the Polaris program, a series of three crewed technology demonstration spaceflights funded by billionaire Jared Isaacman, who has already flown into space aboard the Inspiration4 private space mission aboard a Dragon in September 2021. The first Polaris mission, Polaris Dawn, is scheduled to fly aboard a Dragon in a 2023 mission that will include spacewalks and orbits reaching higher altitudes than previous crewed spacecraft that didn’t go to the Moon.

The second Polaris mission is supposed to fly another crew aboard Dragon and build on Polaris Dawn. And a third Polaris mission is slated to fly aboard the SpaceX Starship, which promises a massive advance in spaceflight capability over existing spacecraft. While the NASA-SpaceX study is focusing on Dragon flying to HST, perhaps on the second Polaris mission, the possibility exists that the study could consider using Starship to visit Hubble.

The NASA press release on this study stated: “There are no plans for NASA to conduct or fund a servicing mission or compete this opportunity; the study is designed to help the agency understand the commercial possibilities.”

Despite this stipulation, any mission designed to boost Hubble into a higher orbit inevitably raises the question of servicing and updating Hubble, along with the matter of the scientific value of an extended HST mission, with or without servicing.

There is no question that HST could benefit from a servicing mission. Three of its six gyroscopes have failed, one of its five instruments is no longer used and two others have had problems. The detectors on Hubble’s instruments are losing effectiveness with time, and other components throughout the telescope are degrading from radiation exposure and from Hubble’s passages between daylight and night conditions on each orbit. In 2021, Hubble lost a month of science operations due to a problem with its payload computer. No instrument on HST is newer than 13 years, and some equipment has been operating in the harsh environment of space for more than 32 years.

| Even if SpaceX and Isaacman of Polaris pick up some of the tab, any servicing component of a mission to Hubble would cost NASA tens and perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars. |

Since NASA spends close to $100 million a year to operate Hubble, the agency requires regular reviews of Hubble’s scientific value. Earlier this year, the Astrophysics Senior Review Subcommittee of NASA’s Astrophysics Division conducted an independent review of nine missions, including Hubble. “Hubble and Chandra occupy the top tier [ranking] given their immense, broad impact on astronomy,” the subcommittee report said. “Both missions are operating at extremely high efficiency, and although they are increasingly showing signs of age, both are likely to continue to generate world-class science throughout the next half decade, operating in concert with JWST as it begins its flagship role.”

In the 2020 Astronomy and Astrophysics Decadal Survey of the National Academies, Hubble was listed at the head of a list of astronomical facilities that are “running and delivering cutting-edge science,” and that “have been extraordinarily productive and cost effective in seeding a steady stream of major scientific discoveries using panchromatic capabilities that are central to their advancing broad decadal scientific priorities.” As mentioned above, astronomers want to conduct joint observations with Webb and Hubble over the next few years. Many astronomers value Hubble’s unique capabilities, particularly for observations in ultraviolet wavelengths. Demand for observing time on HST continues to outstrip availability.

Although there is a consensus among astronomers for continued HST operation, many arguments remain against anything more ambitious than a reboost mission for HST. Diverting any of NASA’s astrophysics money to a Hubble servicing mission would be controversial.

The Hubble servicing missions succeeded in part because of the Space Shuttle’s massive cargo capacity, which was used to carry the new instruments and other equipment that astronauts installed on HST, along with the many tools they required. The Space Shuttle Remote Manipulator System played an important part in getting astronauts to the right places on Hubble. Dragon’s cargo capacity is only a small fraction of the shuttle’s payload bay, and there’s no robot arms for Dragon at the moment. Thus, any servicing mission from a Dragon would be very modest by shuttle standards. A servicing mission involving Starship could be a whole different matter, but that remains a matter of conjecture, at least until Starship proves itself in flight.

Even if SpaceX and Isaacman of Polaris pick up some of the tab, any servicing component of a mission to Hubble would cost NASA tens and perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars. NASA’s astrophysics budget not only has to support ongoing missions, but also upcoming missions such as the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which has had its share of budget issues and also delays caused by the pandemic. Diverting any of NASA’s astrophysics money to a Hubble servicing mission would be controversial.

Hubble Project Manager Patrick Crouse, who for more than a decade has headed the team of engineers that keep HST in working order, has emphasized that Hubble is working well despite its age.

NASA has said that other companies may propose similar studies with spacecraft other than Hubble and Dragon. And this study may identify obstacles to a Dragon mission to Hubble. While this study may lead to new ideas for commercial space exploration, the ultimate importance of this study may be that after years of ambiguity, NASA will begin to have a clear plan for HST's final years.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.