Review: The Martiansby Jeff Foust

|

| Baron speculates that Lowell’s life might have taken a very different direction had he not come home to console his widowed sister and, in the process, become immersed in the growing interest in Mars. |

But the scientist who was the lead author on the paper about the findings said later that, in fact, there were other ways to produce the minerals without invoking life. Joel Hurowitz, a planetary scientist at Stony Brook University, said heating the rocks could create the minerals, although researchers could not find any signs that the rocks had been heated sufficiently.

This finding is not the first time that scientists have spotted a potential biosignature on Mars only to be unable to remove “potential” from its description. Nearly 30 years ago, for example, studies of the Martian meteorite ALH 84001 showed evidence of past Martian life, into putative “microfossils” in the rock, a finding that led to a burst of publicity in August 1996, only to fade as others found alternative, more likely explanations (see “The greatest story on planet Mars: the sequel”, The Space Review, this issue.)

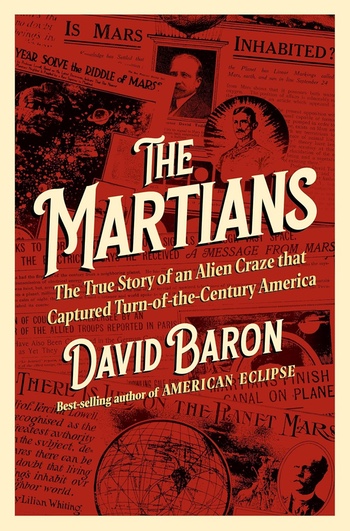

Even the circus around ALH 84001, though, was tame compared to the environment around the turn of the 20th century. The idea that Mars was not just inhabited but home to an alien civilization was accepted by many as astronomers reported seeing features on Mars: the now-infamous canals. The Martians, by David Baron, examines that earlier Mars mania.

The central figure in The Martians is Percival Lowell, a member of a prestigious Boston family who has become synonymous with the observations and promotion of the canals. That work was not a lifelong pursuit: Lowell had first thrown himself into the study of the Far East, living there for years. Baron speculates that Lowell’s life might have taken a very different direction had he not come home to console his widowed sister and, in the process, become immersed in the growing interest in Mars. He soon threw his energies, and wealth, into the study the planet.

Lowell was not the first to claim to see evidence of canali—“channels” in Italian, but inevitably mistranslated into canals—on Mars, but he became perhaps the biggest proponent of the idea that they were artificial structures, constructed by a civilization to direct water from the poles. He built Lowell Observatory in Arizona to observe the planet and supported other observations of the planet, while promoting his findings in lectures, despite the consternation from other astronomers who dismissed his observations and conclusions.

Lowell is the central figure in this book, but hardly the only one. Baron includes others caught up in the era’s fascination with Mars, such as French astronomer and writer Camille Flammarion, author H.G. Wells, and Nikola Tesla, who sought to communicate with the Martians via “electrical disturbances” or radio. (One fictional account of Tesla, run in a boys’ magazine of the time, was titled “To Mars with Tesla,” which today might describe how Elon Musk seeks to fund his own Martian ambitions.) The book, though, revolves around Lowell, and ends with his death in 1916.

By then Mars—at least the Mars imagined by Lowell—was in decline. There was growing evidence that the canals were figments of his and other observers’ imaginations, as their brains tried to make sense of what they saw through their telescope eyepieces. Public interest also faded.

Lowell’s story is well-known, and they have been other biographies of him, but Baron does a good job bringing in various threads about the interest in Mars at the time. The book reveals Lowell to be someone who today might be considered to suffer from bipolar disorder: he suffered from crippling depression at time, but other times could be deeply focused on his work. Baron notes that Lowell, after reading a book by Flammarion that fueled his interest in Mars, wrote a cryptic note inside its front cover: “Hurry.”

| The book reveals Lowell to be someone who today might be considered to suffer from bipolar disorder: he suffered from crippling depression at time, but other times could be deeply focused on his work. |

As for the latest Mars life discovery, researchers like Hurowitz said more analysis was needed to better determine if the minerals might have been excreted by an ancient Martian microbe. The best way to do that would be to bring that rock sample collected by Perseverance back to Earth, where it could be studies in laboratories far more sophisticated than any instrument that could be set to Mars.

Unfortunately, NASA’s fiscal year 2026 budget request would cancel the Mars Sample Return program, even as the agency was working to get it back on track after cost and schedule overruns. At the briefing, Duffy said he believed there was an alternative way to bring the samples back, but disclosed no details about that plan. For now, it is as mysterious as the question of whether Mars might once have life, and potentially as ethereal as its canals.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.