Mapping the dark side of the world (part 3): Replacing ARGON, the SAMOS E-4, and mapping the Moonby Dwayne A. Day

|

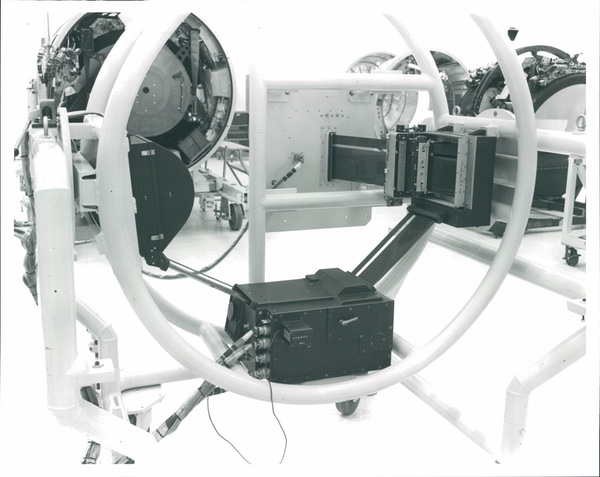

Launch of the seventh ARGON mission in October 1962. (credit: Peter Hunter) |

The SAMOS E-4

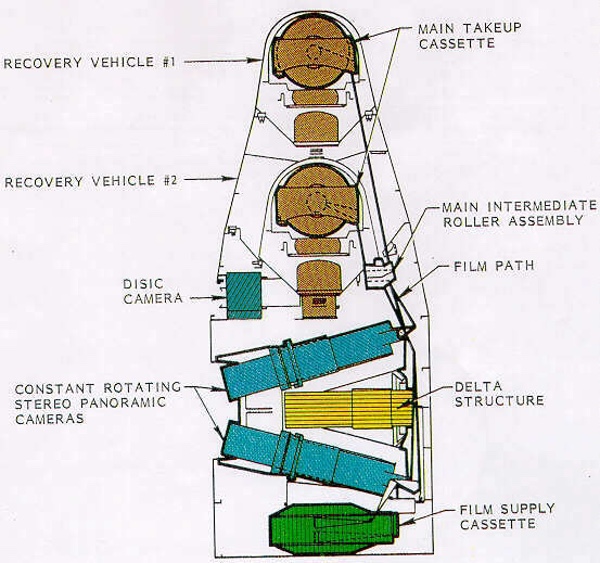

The Air Force had first defined the requirement for a mapping and charting satellite in September 1958. By January 1959, the Air Force refined this into a proposal for a recoverable mapping satellite capable of taking pictures with high geometric fidelity. The Air Force started this as the E-4 SAMOS system, and it was tied to the SAMOS E-5 reconnaissance system, which had a much larger camera. The SAMOS E-4 would use the same type of large recoverable spacecraft that would bring the entire camera back to Earth. The capsule was 72 inches (183 centimeters) in diameter and 84 inches (213 centimeters) long, far bigger than was needed to carry a mapping camera. It also required an Atlas rocket, which was more expensive than the Thor that was used to place ARGON into orbit.[1]

| “It appears that SAFSP does not want to do this job,” Charyk told a brigadier general. “The system is obviously gold plated and fat. It is necessary that the program be scrubbed down to the core and re-estimated.” |

The E-4 was supposed to be a system that provided position accuracies of 500 feet (150 meters) or less. The terrain camera had a 6-inch (15-centimeter) focal length with a f/5.6 lens, and the stellar camera was 3-inch (7.6-centimeter) focal length. The system would have a five-day mission with an apogee of 178 nautical miles (330 kilometers). Ground resolution would be approximately 150 feet (46 meters) during the 90-mile (145-kilometer) perigee over the target area. The film would be 9.5 inches (24 centimeters) wide and 4,000 feet (1,220 meters) long. The stellar image camera would be f/2.5 and produce 4.5-by 4.5-inch (11.4-by-11.4-centimeter) film frames, exposing each frame for four seconds. It would have 2,000 feet (610 meters) of film. Each mission theoretically would provide 50 million square miles (130 million square kilometers) of coverage.[2]

According to an official history of the later HEXAGON Mapping Camera Program, the Air Force’s senior leadership, the Air Staff, “was never more than lukewarm” about the E-4. This resulted in the E-4 being a “tenuous development which was in direct competition” with an interim mapping system proposed by the Advanced Research Projects Agency, and with the ARGON system that entered development along with CORONA. Lockheed had just finished its initial development plan for the E-4 when in May 1959, ARPA directed the Air Force to cancel the program.

In October, the SAMOS Washington office advocated for a camera system known as “412,” which was a new name for the E-4 camera. Major C.E. James proposed that this would be a “logical follow-on to ARGON.” Two cameras were already scheduled for completion by early 1961, with seven more planned, and they offered better performance than ARGON. James claimed that the first flight could take place by August 1961.

The HEXAGON history noted that by pursuing E-4, the “cumbersome ARGON management complex, which then included the Army Mapping Service, the National Photographic Interpretation Center, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the West Coast ARGON office,” could be simplified. But while the bureaucratic arrangement might be less complicated, the E-4 was a larger and more complex spacecraft.

In December 1960, Joseph Charyk, the Air Force civilian responsible for overseeing the reconnaissance satellite program, directed that the “412” camera be integrated into SAMOS and the contracts expanded to include three flight cameras, two test articles, and four follow-on models. Three Atlas Agena rockets would be provided for the missions.[3]

The head of the West Coast satellite program office was concerned that the E-4 was needlessly complicating the overall satellite effort, and would be costly, because it now appeared to have precedence over several other programs.

By February 1961, Charyk directed that the E-4 would have to be developed within existing funding limits. E-4 was generally referred to as “Program 1A” at this time for security reasons. By April 1961, the design was relatively firm. The plan was for launches in March, June, and September 1962, followed by the first of five supplemental payloads launching in April 1963.[4]

The program began to lose support by around the same time as it was being formalized. The Army was made responsible for managing “a single geodetic and mapping program to meet Defense Department requirements.” Army officials then began planning for an ambitious research and development program to support this, which the Air Force opposed.

In late May 1961, the Director of Defense Research and Engineering took on the evaluation of mapping satellite responsibilities. Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric authorized the continuation of procurement of four cameras for E-4, but instructed Charyk to suspend procurement for boosters and spare vehicles. Soon the E-4 program was limited to those four vehicles. The camera payload continued in development for another six months. Some in the Air Force hoped that they would be given the go-ahead to launch them in the near future. But the cost for the program was growing.[5]

Upon learning of the cost, Charyk was unhappy. “It appears that SAFSP does not want to do this job,” he told a brigadier general. “The system is obviously gold plated and fat. It is necessary that the program be scrubbed down to the core and re-estimated.” (SAFSP was the Air Force office in Los Angeles that was then responsible for reconnaissance satellite photos. By fall 1961, Charyk was named as the first Director of the National Reconnaissance Office, and SAFSP was directly under his control.) Charyk might have been influenced by the fact that CORONA hardware, including the Thor booster, was cheaper than what the Air Force was proposing for any of its SAMOS projects.

The first two ARGON missions, launched in early 1961, had suffered reentry failures. The second two, in June and July, had suffered launch failures. The first ARGON success did not occur until May 1962.

By early January 1962, Charyk ordered that as the four payloads were completed, they would be stored in a readiness-in-9-months flight condition. Any decision to fly would require the provision of substantial funds for launch, boosters, and space vehicle costs.[6]

Although four E-4 camera systems were apparently built, no photos or drawings of the cameras or overall systems survived. The hardware was almost certainly destroyed sometime after program cancellation.

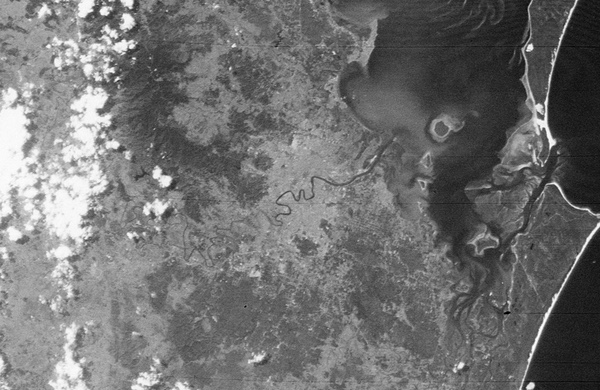

An ARGON mapping camera image of Brisbane, taken in October 1962. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

The follow-on program and the feud

In December 1962, after three successful ARGON flights, now-Director of the National Reconnaissance Office Joseph V. Charyk sent a memo to the Assistant Secretary of the Army concerning the development of ARGON PRIME, a more advanced geodetic satellite system to replace ARGON. Herbert York had halted ARGON PRIME in August. The proposal was called ARGON PRIME, or A’, after the sequence established with the CORONA cameras. The system would rely upon most of the existing hardware for the ARGON program, but would also include a new 12- or 18-inch (30- or 45-centimeter) focal length terrain camera and a 6-inch (15-centimeter) focal length stellar camera, considerably bigger than ARGON’s cameras and the SAMOS E-4 camera.

The Air Force also apparently wanted to modify CORONA’s panoramic photography to include a reseau, a grid etched on the lens system of a camera which shows up in the image and allows photogrammetrists to make accurate measurements of the terrain. This grid survives the warping and distortion produced during processing of the film. But it could also affect the spotting of small targets on the imagery.

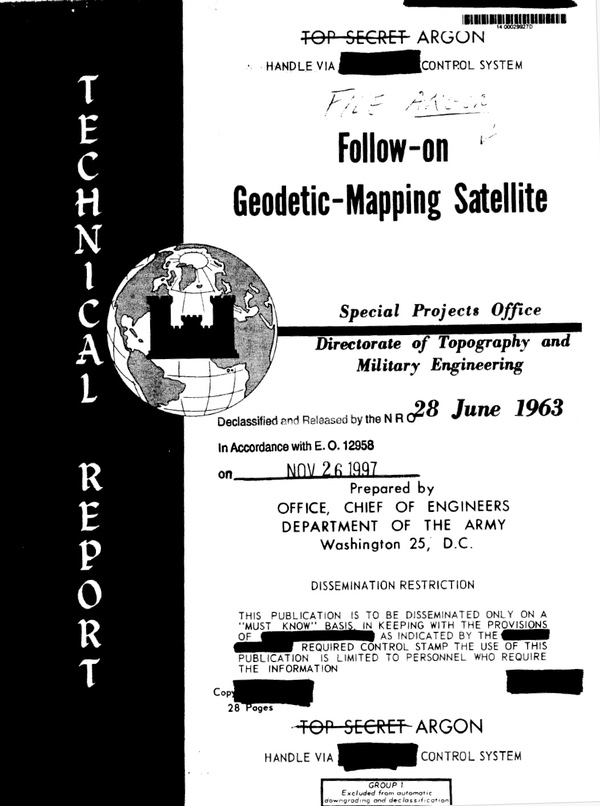

In 1963, the US Army proposed a mapping satellite known as ARGON PRIME. It was not accepted. It would have also operated in polar orbit. Senior intelligence officials determined that in the future, mapping cameras should be included in reconnaissance missions. (credit: NRO) |

In June 1963, the Chief of Engineers, Department of the Army, produced a report on a “Follow-On Geodetic-Mapping Satellite.” This was a more detailed version of the Army’s earlier ARGON PRIME proposal. This new satellite was to produce imagery useful not only for making large-scale maps (such as that already provided by the ARGON system) but also for medium-scale maps as well. ARGON was used for 1:250,000 maps, whereas ARGON PRIME could be used to produce 1:50,000 scale maps. ARGON PRIME would use two cameras. The first would be a precision vertical mapping camera with a 12-inch focal length and a 9x14.5-inch (23x37-centimeter) film format. The second camera would be a 6-inch focal length stellar camera, mounted perpendicularly to the vertical camera. It would provide accurate stellar images at the same time that the vertical camera photographed the ground. These two images, coupled with a timer in the Agena D vehicle (which read out the time and date onto the film) could provide highly accurate data. The system would return 100 pounds (45 kilograms) of film.[7] Charyk’s reaction to this new proposal is unknown, but it apparently was not well-received, for the Army quickly began looking for alternatives.

| Clearly what the Army wanted was a satellite essentially dedicated to its mapping mission. The Air Force also wanted its own mapping satellite. |

In October 1963, Brigadier General George H. Walker, Army Director of Topography and Military Engineering, sent a report to the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research and Development. The report was an analysis of a concept for a “combination satellite system.” The proposal was to develop a version of the current KH-4 CORONA satellite with only one 24-inch (61-centimeter) panoramic camera instead of two (like the earlier KH-3 version). In place of the missing camera, a 12- to 18-inch mapping camera would be installed. [8]

But clearly what the Army wanted was a satellite essentially dedicated to its mapping mission. The Air Force also wanted its own mapping satellite. The CIA, which was then in the midst of a battle within the NRO to maintain control of the CORONA system, was interested in not harming its own program, not giving the Air Force any more leverage, and not impacting the national reconnaissance effort. CIA officials did not want reseau grids over CORONA images, and did not want to lose of one of the two CORONA cameras carried on KH-4 CORONA MURAL missions.

Replacing the Stellar-Index camera

By the end of 1962, ARGON had achieved three successes out of seven missions. CORONA Index, and later Stellar-Index cameras, however, were flying on almost every CORONA mission, and CORONA was launching nearly once a month. But despite its excellent performance record, the Itek Stellar-Index camera lacked the focal length needed to meet future mapping, charting, and geodesy (MC&G) accuracy requirements. Military requirements—and capabilities—were always increasing the demand for higher and higher accuracy. The Army clearly wanted a camera with a focal length of at least 12 inches (the Stellar-Index camera was 1.5 inches). But the Army was apparently unable to convince the leaders of the intelligence community that such a large camera was justified, or at least worth the cost. What the MC&G community wanted was something like the ARGON camera, only flown on the CORONA vehicle. This way they would not have to sacrifice one of the panoramic cameras, like the Army had proposed with its “combination satellite.” (See: “Mapping the dark side of the world (part 2): supplementing, and supplanting, the ARGON geodetic satellite program,” The Space Review, November 24, 2025).

Assistant Secretary of Defense Eugene Fubini served as Deputy Director, Research and Engineering (DDR&E), starting in 1963. He had replaced Herbert York, who had earlier killed the Army’s plan for ARGON PRIME. Because of an ongoing fight over the NRO, the DDR&E had been designated monitor for the National Reconnaissance Program—the name of the overall American strategic reconnaissance effort. In fall 1964, Fubini proposed that instead of developing an ARGON follow-on camera, they should incorporate a reseau into the CORONA imagery (as the Air Force had proposed) and also incorporate a new Stellar-Index camera into existing CORONA satellites, replacing the existing one.

In October 1964, the Director of Central Intelligence, John McCone, replied to Fubini’s proposal. McCone emphasized that, although he thought this capability was important (he noted the high expense of the Department of Defense’s mapping effort and the economies that this modification would produce), “the mapping mission must at no time take precedence over the intelligence mission or compete with the intelligence mission for funds, available launchers, and payloads.”[9] McCone was also worried about the added complexity of the Stellar-Index system and suggested that, to ensure that it did not impact any of the CORONA missions, the camera first be tested separately during three or four non-CORONA launches before being incorporated into the CORONA system. McCone did not mention the issue of the reseau grid for the CORONA panoramic photography.

Fubini then sent a memo to Director of the NRO Brockway Macmillan, who had replaced Charyk in March 1963, proposing the reseau for the CORONA camera and a new 3-inch Stellar-Index camera. He also apparently proposed that the new mapping camera could be incorporated into GAMBIT satellites as well.[10]

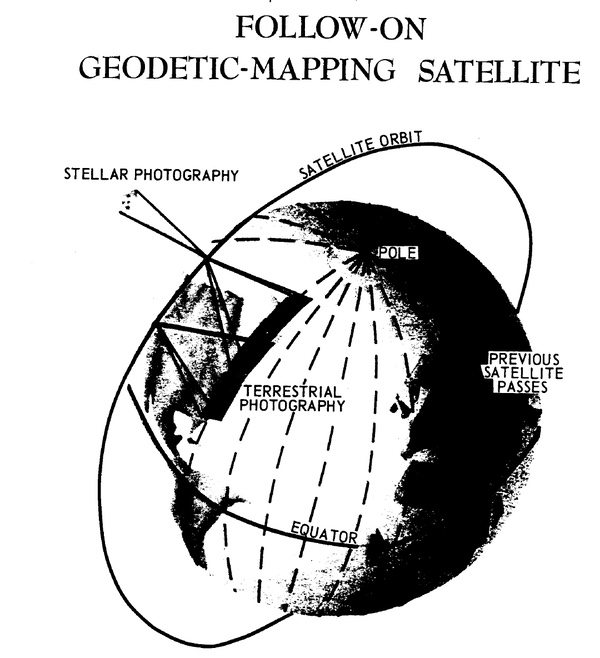

A DISIC camera system mounted in a holding frame. KH-4B CORONA cameras are at back left and right. |

DISIC, the Dual Image Stellar Index Camera

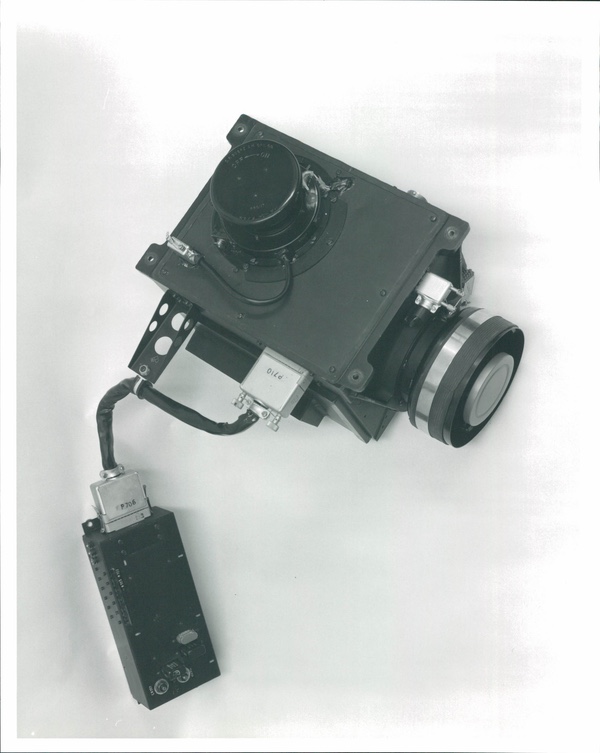

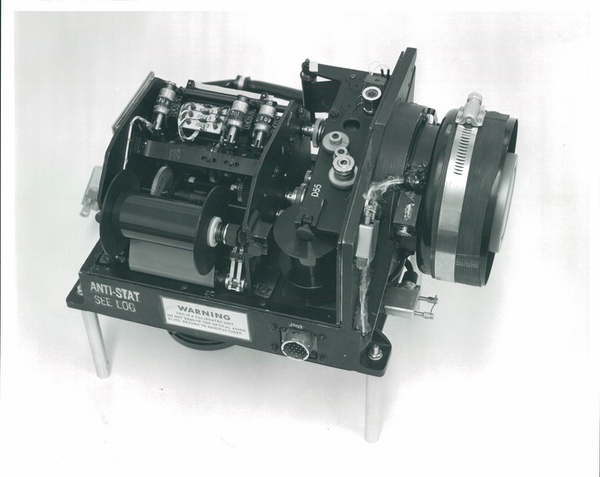

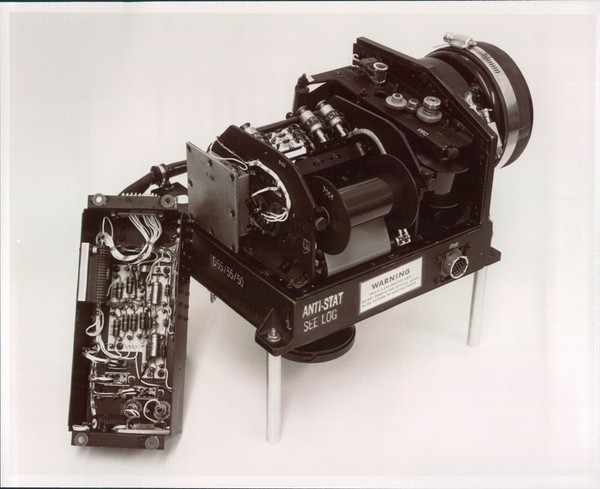

After some further discussion, the parties reached an agreement: a new camera, based upon the existing ARGON camera, would be developed for incorporation in the CORONA satellites. McCone’s proposal for testing the new camera separately was apparently rejected. Fubini’s proposal for a reseau grid for the CORONA camera was also rejected.

The KH-4B was the final version of the CORONA reconnaissance satellite and was equipped with the Dual Image Stellar Index Camera for mapping purposes. (credit: NRO) |

In the spring of 1965, Fairchild Camera and Instrument Company, which had produced the ARGON camera, was asked to supply a nearly identical version of the camera for use on CORONA. The major difference was that, unlike the ARGON lens, the new camera’s lens would emphasize resolution over distortion-free imagery. The ARGON lens had striven for minimal distortion, but sacrificed resolution. The MC&G experts now felt confident enough that they could compensate for lens distortion and they therefore strove for the best resolution possible with the limited focal length.[11]

The Dual Image Stellar Index Camera – DISIC for short - flew aboard the 17 KH-4B CORONA spacecraft launched between 1967 and 1972. (credit: NRO) |

The terrain camera had a focal length of three inches. Ground resolution was improved to approximately 100–400 feet (30–120 meters). It used an lkogon lens with a film format of 4.5 by 4.5 inches (11.4 by 11.4 centimeters) and a rotary shutter. It imaged an area approximately 140 miles (225 kilometers) on a side: the same width as a CORONA panoramic swath, just like the earlier Stellar-Index camera. It could be preset to operate at 9.375, 12.5, 15.625, or 18.75 seconds per cycle, based on the planned spacecraft altitude. The stellar photography was provided by two three-inch focal length cameras using 35 mm film. They were mounted port and starboard and tilted ten degrees above the horizontal axis. The terrain and stellar cameras each carried 2,000 feet (610 meters) of film.[12]

This new camera was called the Dual Image Stellar Index Camera—DISIC for short—and It flew aboard the 17 KH-4B CORONA spacecraft launched between 1967 and 1972. Only one DISIC was flown for each spacecraft compared to the two Stellar-Index cameras carried on earlier missions. A special “cut and splice box’’ was used to direct the film into either A or B Satellite Recovery Vehicles. A Doppler beacon was later added to the spacecraft to improve tracking and orbit determination.

One of the last CORONA missions, launched in September 1971. This spacecraft included a DISIC mapping camera. (credit: Peter Hunter) |

In June 1966, before DISIC even began flying, Itek issued a report on a “Geodetic Orbital Photographic Satellite System,” otherwise known as GOPSS. GOPSS was a proposal to use not only a satellite, but also tracking and auxiliary data to produce an accurate landmark catalogue. This would then help in determining the geophysical parameters and other factors affecting the satellite orbits.[13]

In 1966, Itek proposed the Geodetic Orbital Photographic System, or GOPSS, a large mapping camera in a dedicated satellite. Although it was not accepted, it formed the basis of the later HEXAGON Mapping Camera. (credit: NRO) |

But by this time the idea of dedicated mapping satellites (like the earlier ARGON and E-4 programs) was a non-starter: mapping cameras would only be flown with reconnaissance cameras. DISIC was the ultimate refinement of the mapping cameras developed for the early American military space program. In the 1970s it was replaced by another dedicated mapping camera carried aboard CORONA’s successor, the KH-9 HEXAGON, which began flying in 1971. The HEXAGON Mapping Camera satisfied the Army’s earlier ARGON PRIME requirement for a 12-inch focal length camera. The original goal for a large film load could be accommodated considering HEXAGON’s much larger mass margins and a dedicated reentry vehicle for mapping camera film.

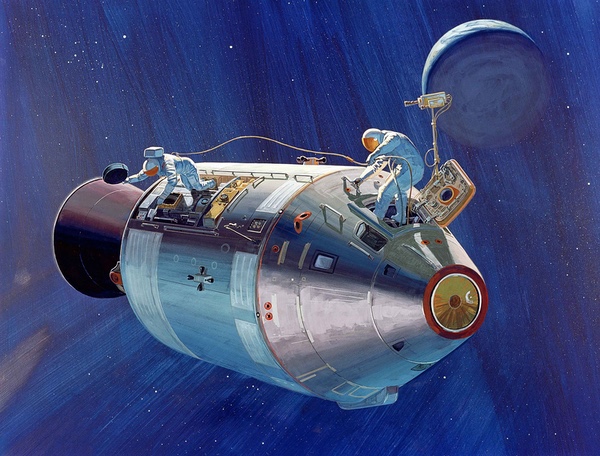

Apollo 15, 16, and 17 carried instruments in the Service Module, including two cameras, a panoramic camera derived from an aerial reconnaissance camera, and the Metric Camera System, derived from the DISIC mapping camera developed for the CORONA program. (credit: NASA) |

Mapping cameras for Apollo

Despite the incredible secrecy surrounding American reconnaissance and geodetic cameras, similar or identical versions of these cameras were used in a totally unclassified program aboard Apollo missions 15, 16, and 17 in lunar orbit. Rather surprisingly, no one in the media or later in the academic community had ever connected the reconnaissance systems carried on Apollo with the ones flown by the CIA and Air Force.[14]

| Rather surprisingly, no one in the media or later in the academic community had ever connected the reconnaissance systems carried on Apollo with the ones flown by the CIA and Air Force. |

Several reconnaissance cameras developed for space were adapted for aerial use. The early CORONA camera was adapted to serve as the “C-Camera” for the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft in the early 1960s. By the mid-1960s, Itek applied the technology from the KH-3 CORONA panoramic camera for aerial use aboard the U-2, A-12, and later SR-71 aircraft. The camera was highly modified (unlike the C-Camera) and essentially maintained only the KH-3’s lens assembly. The CIA called it the Optical Bar Camera or OBC. The US Air Force designated it the KA-80A. A modified version of the KA-80A was fitted inside the Apollo Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay.

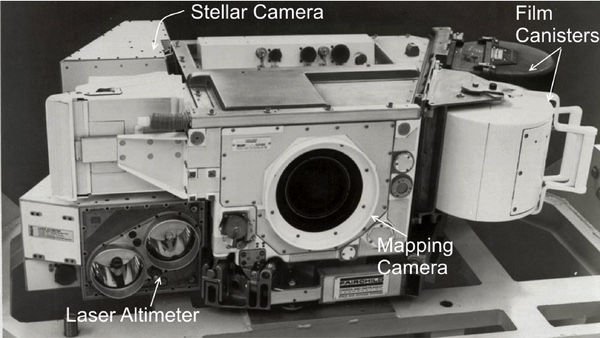

Fairchild also adapted a version of DISIC for use on the Apollo missions, where it was referred to as the Metric Camera System. It used essentially the same DISIC design, with its 3-inch (76 mm) f/4.5 lens. A range of exposures from 1/15 to 1/240 seconds could be selected. The film magazine held 1,509 feet (460 meters) of film, enough for 3,600 frames. The camera compensated for the movement of the spacecraft and the velocity over height value determining this was set by the Command Module Pilot in lunar orbit. Successive frames overlapped by 78% and alternate frames by 57%.

The Apollo Metric Camera was derived from the DISIC design, but also included a laser altimeter. It was carried on three Apollo missions. (credit: NASA) |

The MCS also included a stellar camera with a three-inch f/2.8 lens. The stellar camera operated in concert with the terrain camera, also taking 3,600 frames. It was mounted with its optical axis 96 degrees to the terrain camera. Unlike DISIC, the MCS had only one stellar camera. The film from both cameras was collected in a single takeup cassette. The Command Module Pilot retrieved this cassette, along with the panoramic camera cassette, during a spacewalk on the return trip from the Moon.

| The revolution in map making that CORONA, ARGON, and their successors represented was felt in all areas of American cartography, and US maps frequently became hot commodities in foreign nations as well. |

The one major difference between DISIC and the MCS was the addition of a laser altimeter aligned parallel to the axis of the terrain camera. A ruby laser emitted a very short pulse of red light at the time of each terrain camera exposure. A photomultiplier tube detected the portion of the pulse that was reflected from the Moon. By measuring the round-trip travel time and multiplying it by half the speed of light, the precise altitude of the spacecraft above the Moon’s surface could be determined. Together, the panoramic camera and MCS provided highly useful imagery of the Moon.[15]

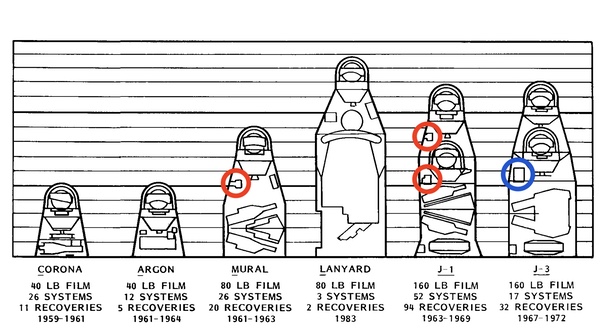

During the same time that the ARGON mapping missions were flying, the National Reconnaissance Office was equipping CORONA reconnaissance satellites with Index, and later Stellar-Index cameras (circled in red) that had some mapping capability. Later KH-4B CORONA satellites were equipped with the DISIC mapping camera. (credit: NRO) |

Revolutions in mapping

By the early 1960s, the US military’s World Geodetic System model of the Soviet Union was far better than it had been only a few years earlier, but it was still highly idiosyncratic. The location of nearly all Strategic Air Command targets in the USSR had been accurately determined and extensive bombing routes had been charted for SAC’s B-52 Stratofortresses. However, most Soviet territory remained uncharted. But as time progressed, Soviet air defenses such as the SA-200 (NATO designation: SA-5 GAMMON) drove SAC’s bombers from the high thin air and forced them to make their penetrations into Soviet airspace at low altitude. There was thus an ever-increasing demand for accurate charts to ensure that poorly mapped mountain ranges did not surprise a B-52.

Around 1965, Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay ordered that ACIC revise all its World Aeronautical Charts of the Soviet Union.[16] LeMay wanted complete charts of the entire country so that he could destroy it. This involved a massive effort that soon occupied all the relevant agencies, the intelligence and defense communities.

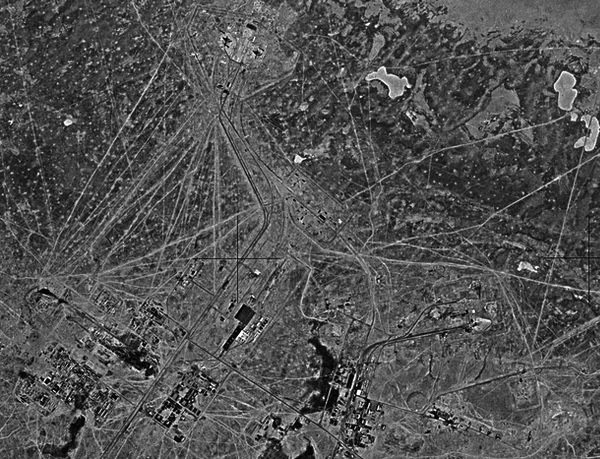

A HEXAGON Mapping Camera image of the Soviet launch complex at Baikonur, taken in 1975. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

In 1965–1966, the civilian US Geological Survey (USGS) was granted access to CORONA and ARGON data for production of maps of US and connected territory, such as Canada and Mexico. This resulted in a remarkably close working relationship between the civilian and military mapping communities. Lowell Starr, a civilian cartographer with the USGS, stated that the CORONA materials were used to update already existing maps of the United States and by this time using the materials was relatively easy:

A trained employee could view a roll of CORONA film and quickly annotate the related maps by using USGS criteria to decide whether or not the maps would require revision. This process was so reliable that we later just reprinted some of the inspected maps and included the statement ‘No Revision Required, Inspected 19_.’ Of course, maps which required revision would be corrected by conventional methods.[17]

The space-based capability made it much easier to revise the existing maps. The revolution in map making that CORONA, ARGON, and their successors represented was felt in all areas of American cartography, and US maps frequently became hot commodities in foreign nations as well: one civilian geodesist remembered a little old lady from the Soviet embassy in Washington who routinely showed up at a US government store to buy a complete set of all the latest maps of the USSR—maps produced from top secret reconnaissance satellites flying over the Soviet Union.

As William Mahoney stated:

CORONA wasn’t just an intelligence and target location tool. It was also a major instrument for compiling the cartographic and digital products that were necessary to support ground forces. By 1969, we could reliably predict any position on the Earth’s surface to within 450 feet [150 meters] with a 90 percent accuracy rate. We put the cross hairs on the target that made our counterforce credible[18].

Many targets were known to an even higher accuracy. Over time, the veil of geodetic uncertainty that covered the Soviet landmass was peeled away, but the demand for better and more flexible data never abated.

In 1959, Amrom Katz at RAND had voiced his opinions on what the Air Force should do when developing a satellite mapping program. Neither the Air Force nor the rest of the intelligence community pursued the program in the way Katz believed they should. But if Katz was aware of how satellite mapping evolved over the following decade, we do not know his thoughts. Based upon what is clear about his character, his opinions would have been strong, and amusing.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of the following people in the preparation of this account, many of whom are sadly now deceased: Charles Ruzek, Frank Madden, Amrom Katz, William Harris, Dick Buenneke, Bill King, Dino Brugioni, and Charlie Murphy. Thanks as well to Harry Stranger for the ARGON photos.

Note: a future article will cover the HEXAGON Mapping Camera, if the author ever gets around to writing it.

Endnotes

- National Reconnaissance Office, “HEXAGON (KH-9) Mapping Camera Program and Evolution,” December 1982, p. 47.

- Ibid, p. 48. Note: the f-number (such as f/5.6 or f/2.5) is a measure of the light-gathering ability of an optical system such as a camera lens. It is defined as the ratio of the system’s focal length to the diameter of the aperture. The lower the number, the larger the aperture and the more light that is let into the camera in a shorter period of time. Lower f-number lenses tend to be short and wide and quickly let light into the camera.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 49.

- Ibid, p. 50.

- Ibid.

- “Technical Report: Follow-on Geodetic Mapping Satellite,” Special Projects Of. flee, Directorate of Topography and Military Engineering, Prepared by Office, Chief of Engineers, Department of the Army, June 28, 1963, NRRF 3/C/0013.

- Geo. H. Walker, Brigadier General, USA, Director of Topography and Military Engineering, to Assistant Director for Mapping, Charting and Geodesy, Defense Intelligence Agency, “Proposed Combination Satellite System,” 16 October, 1963, with attached: Geo. H. Walker, Director of Topography and Military Engineering, to Assistant Secretary of the Army (R&D), “Proposed Combination Satellite System,” [n.d.], NRRF 2/A/0016.

- John A. McCone, Director of Central Intelligence, to Honorable Eugene G. Fubini, Assistant Secretary of Defense (Deputy Director, Research and Engineering), Oct 6, 1964, NRRF 1/A/0071. Why McCone was worried about this new mapping camera is unknown, since CORONA had been flying without incident with the Stellar-Index cameras for over two years and the new camera would only replace the earlier camera in much the same manner.

- Albert D. Wheelon, Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, to Director of Central Intelligence, “Review of the Geodetic Satellite Mapping Proposals of Or. Fubinl,” 10 November 1964, NRRF 1IC/0088. It is not clear from this second-hand account which mapping camera Fubini was proposing for GAMBIT - the earlier Stellar-Index camera, which did fly on GAMBIT, or the later OISIC camera (which may have flown on later versions of the GAMBIT).

- William C. Mahoney letter to Dwayne A. Day, May 5, 1997.

- National Reconnaissance Office Data Book “The KH-4B Camera System,” September 1967, Record Group 263, “CORONA Hard Copy Materials,” National Archives and Records Administration, p. 9.

- Itek Corporation, “Feasibility Study Final Report: Geodetic Orbital Photographic Satellite System,” Volume 1, Program Compendium and Conclusions, June 1966, NRRF 4/E/0006.

- The CIA was worried at the time that the media would draw such a conclusion. See John N. McMahon, SPS/DOS&T, Memorandum for Security Staff, OSA, “APOLLO Lunar Photographic System Ef. fort Carried on at Itek Corporation,” August 18, 1965, NRRF 1/D/0016.

- Harold Masursky, G.W. Colton, and Farouk EI-Baz, eds., Apollo Over the Moon: A View From Orbit (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1978), pp.9-12.

- Dino Brugioni, telephone interview with Dwayne A. Day, March 2, 1997.

- Lowell E. Starr, comments at Piercing the Curtain: CORONA and the Revolution in Intelligence symposium at the George Washington University, May 23-24, 1995.

- Mahoney, ibid.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.