High Jump: the JUMPSEAT signals intelligence satelliteby Dwayne A. Day

|

| By the mid-1960s, signals intelligence experts began to consider launching signals intelligence satellites into higher orbits. This led to two different new signals intelligence satellites: CANYON and JUMPSEAT. |

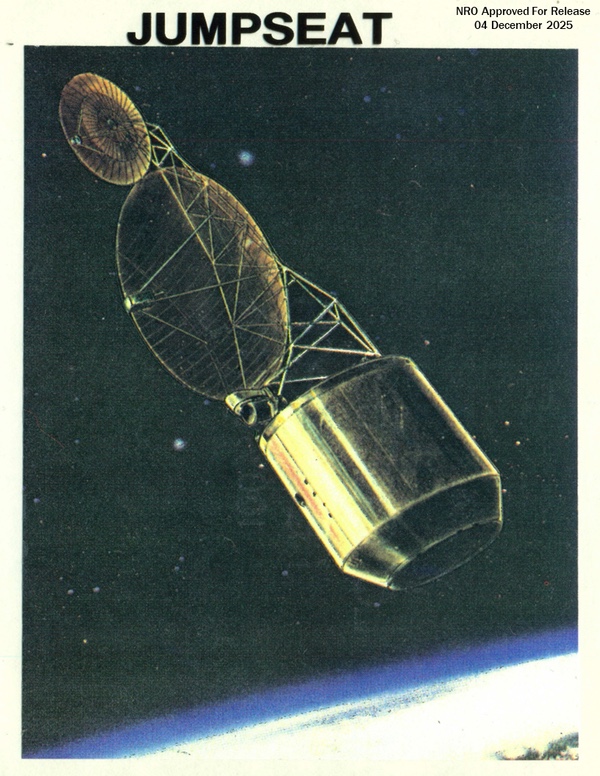

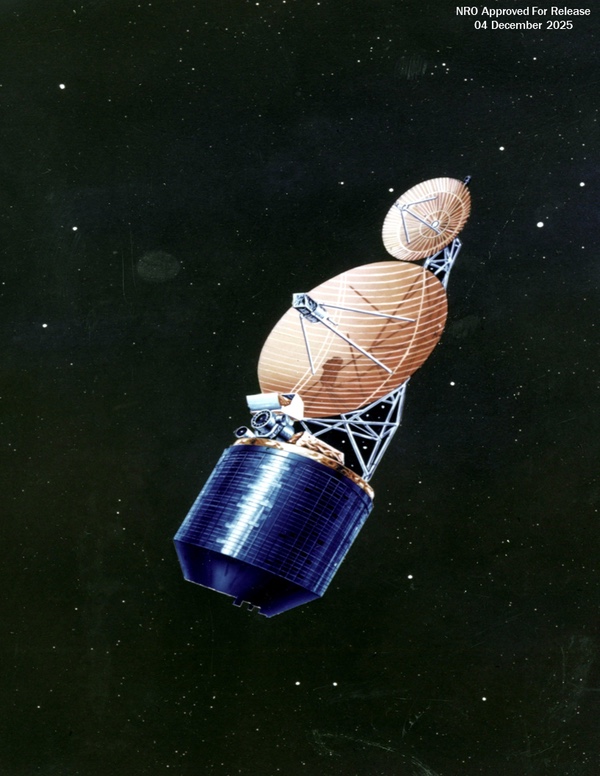

The satellite was named JUMPSEAT, and it was the first of a new kind of signals intelligence collector. It was equipped with two large dish antennas and a small telescope at the base of its “antenna farm.” In orbit, it flew with its spinning bus covered with solar panels up, and its antenna farm pointed down toward the Earth. In December 2025, the National Reconnaissance Office declassified the JUMPSEAT signals intelligence satellite, announcing it on January 28. Eight JUMPSEAT satellites were launched from 1971 to 1987, and the program was finally shut down in 2006—meaning that at least one satellite lasted 19 years or longer in orbit. Although the NRO provided only a limited amount of information on JUMPSEAT, in a press release the office indicated that it would reveal more information in the future. Most notably, the NRO released over a half-dozen photos of the early spacecraft, including models, artwork, and flight hardware.

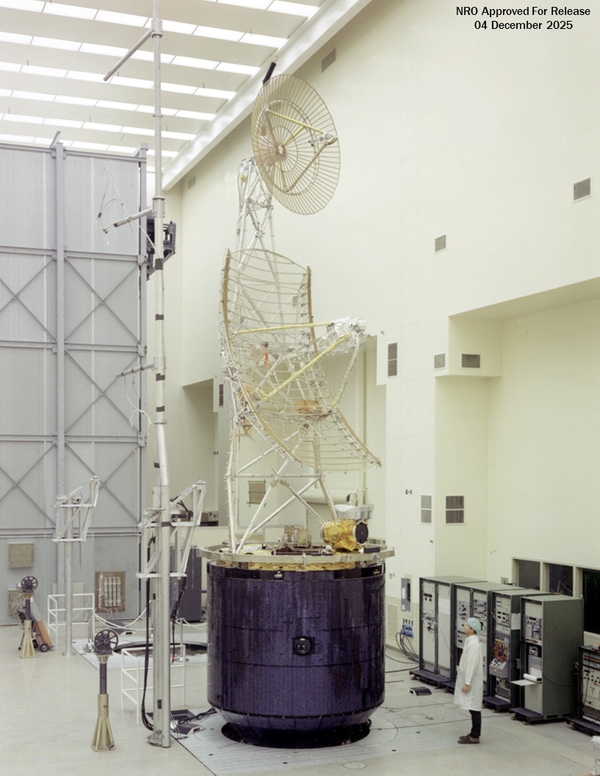

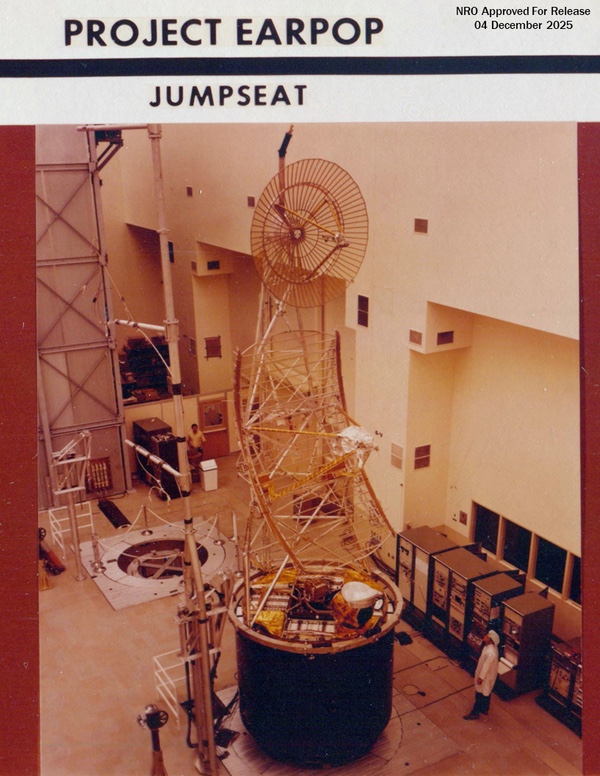

The JUMPSEAT satellites were manufactured by Hughes, which gained extensive experience in spin-stabilized high-altitude satellites beginning in the 1960s. Note that the big dish is not fully deployed. It appears to have had wings that folded out after reaching orbit. (credit: NRO) |

Origins of JUMPSEAT

Starting in the late 1950s, the Air Force, CIA, and Navy began developing systems that could collect radar and other signals from space. The Navy was the first to orbit a radar detector in 1960 as part of a program named GRAB. The Air Force also sought to collect radar signals using both dedicated satellites and payloads attached to other satellites. The CIA was interested in determining if the Soviet Union was trying to track and interfere with its satellites. These efforts were the natural outgrowth of existing projects to put signals intelligence sensors on aircraft, ships, and submarines that had proliferated as the Cold War progressed and the United States military developed a greater appreciation for Soviet radar capabilities.

By 1961, multiple satellite intelligence programs were loosely coordinated under the direction of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). The Navy satellites were developed by a special component of the NRO centered at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC, and known as Program C. The Air Force component of the NRO, known as Program A and based in Los Angeles, was responsible for developing signals intelligence satellites as well as photographic reconnaissance satellites.

Throughout the 1960s, the signals intelligence projects grew more diverse. The Navy continued to develop the GRAB and later POPPY programs, while the Air Force pursued both large signals intelligence satellites as part of Program 770, and smaller suitcase-sized satellites as part of Program 11 (later Program 989). These satellites targeted radars of multiple types, such as air search radars and big, powerful anti-ballistic missile radars. They also focused on other signals such as navigational beacons and communications, including Soviet air traffic control communications. The smaller satellites had many different names such as PUNDIT, MAGNUM, SAVANT, TIVOLI, LAMPAN, TOPHAT, and ARROYO. The satellites were all contained within a security compartment amusingly named EARPOP. (See “A flower in the polar sky: the POPPY signals intelligence satellite and ocean surveillance,” The Space Review, April 28, 2008; “Little Wizards: Signals intelligence satellites during the Cold War,” The Space Review, August 2, 2021; “And the sky full of stars: American signals intelligence satellites and the Vietnam War”, The Space Review, February 12, 2018.)

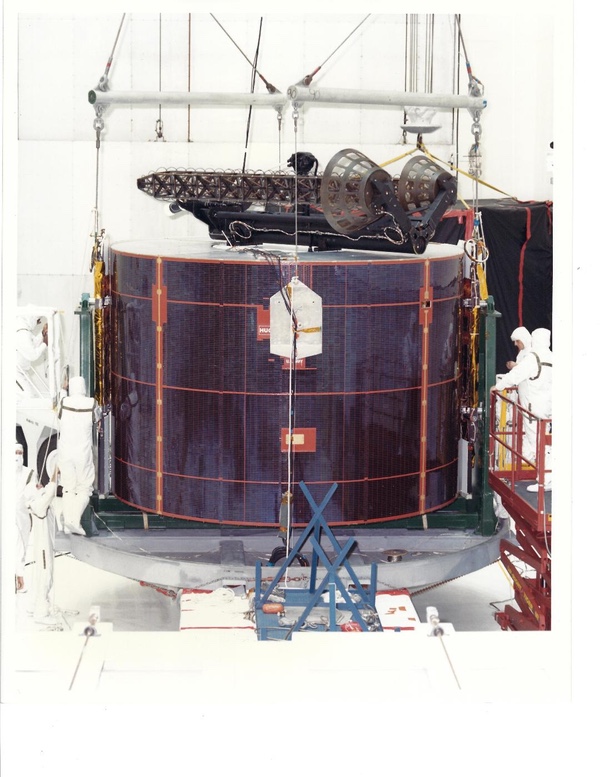

Slightly different photo of the same JUMPSEAT satellite in the factory. “EARPOP” was the security compartment for signals intelligence satellites at the time. (credit: NRO) |

The satellites all operated in low Earth orbit, which placed them relatively close to their targets, but limited the amount of time they could collect emissions before moving out of range. The GRAB and POPPY satellites beamed their collected signals directly down to ground stations as soon as they gathered them, whereas many of the others recorded them on sometimes-problematic tape recorders for replay when the satellite was in view of a ground station.

| The newly released images of the JUMPSEAT satellites, and the fact sheet about the satellite from the NRO, indicate that JUMPSEAT carried several different antennas for collecting signals. |

By the mid-1960s, signals intelligence experts began to consider launching signals intelligence satellites into higher orbits. From a higher perch, the satellites could collect signals for longer periods of time, including intermittent signals such as radars that were turned on and off as needed. A satellite in a high orbit could also send its data directly to a ground station in “near-real time,” where newer and more powerful computers could process their data in minutes rather than the weeks and even months it took to process signals early in the decade. This led to two different new signals intelligence satellites: CANYON and JUMPSEAT. CANYON, which remains classified, was designed to intercept communications between Soviet microwave towers that crisscrossed the vast Soviet landmass.

The basic outlines of the JUMPSEAT program have been known for several decades. Its name was revealed in the mid-1980s and its unusual orbit had been observed since the 1970s. Its overall mission had also been guessed, without much certainty, by independent observers in the 1980s. The NRO contract for JUMPSEAT was awarded to Hughes Aircraft Company in 1967. At this time, debate within the intelligence community about the capabilities of Soviet anti-ballistic missiles (ABM) was reaching a fever pitch. Detecting ABM signals and other related intelligence was a key priority for JUMPSEAT. (See “From TACSAT to JUMPSEAT: Hughes and the top secret Gyrostat satellite gamble,” The Space Review, December 21, 2020.)

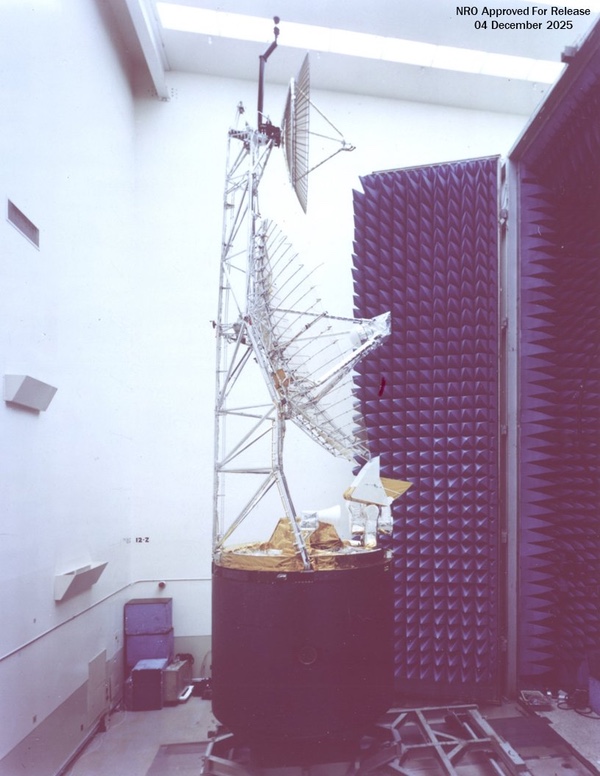

This appears to be a different satellite than the one in the other photos. Note the different (and additional) sensors near the base of the de-spun platform. (credit: NRO) |

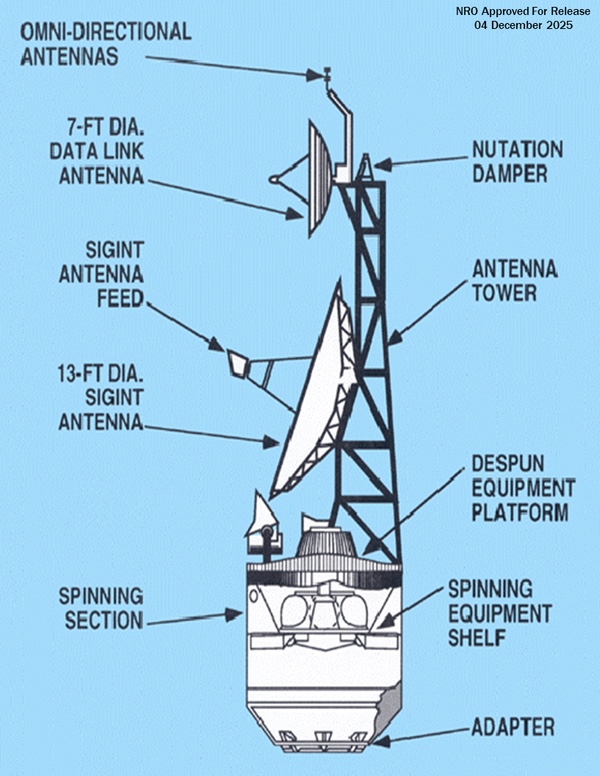

JUMPSEAT was equipped with a large antenna nearly four meters (13 feet) in diameter for collecting radar, communications, and other emissions from the ground, and a smaller antenna for relaying that data to a ground station. JUMPSEAT was a SIGINT satellite. SIGINT is the overall term for the collection of electronic transmissions. SIGINT also includes electronic intelligence (ELINT), which usually means the collection of radar signals; and communications intelligence, or COMINT. Many of the NRO’s smaller satellites were ELINT satellites.

At the time JUMPSEAT entered development, the NRO already operated large SIGINT satellites in low Earth orbit as part of Program 770. By the latter 1960s, a series of Program 770 satellites known as MULTIGROUP was being replaced by a new series named STRAWMAN, equipped with multiple antennas. Operating in low Earth orbit, the STRAWMAN satellites did not spend much time over Soviet territory. JUMPSEAT originated as a higher-altitude replacement for STRAWMAN, with a payload for detecting the elusive ABM radar signals. The newly released images of the JUMPSEAT satellites, and the fact sheet about the satellite from the NRO, indicate that JUMPSEAT carried several different antennas for collecting signals. It also carried additional small payloads, some of which remain enigmatic.

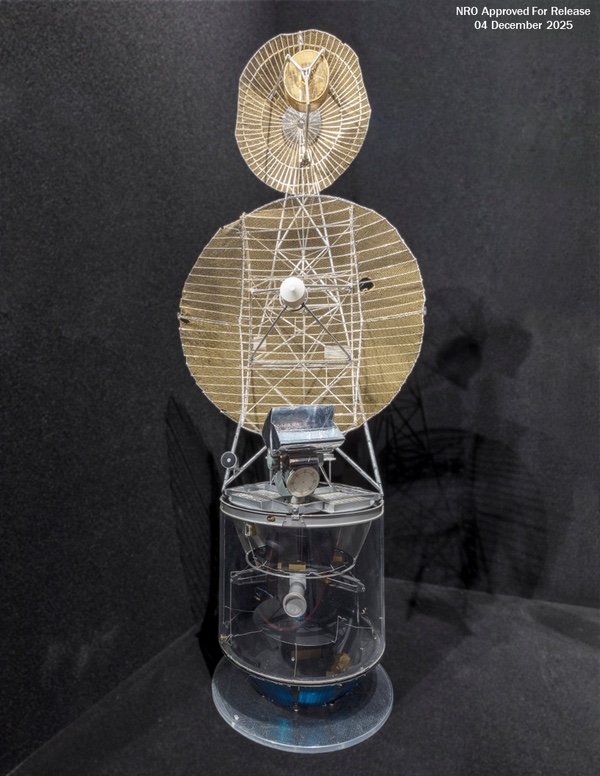

Close up of part of the JUMPSEAT model. JUMPSEAT was equipped with at least one staring infrared sensor for detecting short-burn rockets, such as Soviet anti-ballistic missiles. It could also detect reentry vehicles during tests. It appears that an additional sensor was mounted above the infrared sensor. (credit: NRO) |

Infrared from high orbit

About the same time that TRW was beginning work on the Defense Support Program infrared early warning satellite for the Air Force, and Hughes was successfully bidding for the JUMPSEAT signals intelligence payload for the NRO, another infrared sensor mission was gaining support in the USAF. The new mission appears to have started out in the same organization, Space and Missile Systems Organization (SAMSO), that created the Program 949 (Defense Support Program). The infrared mission apparently did not originate in the much more secretive NRO.

In March 1967, the Air Force’s senior leadership presented the results of a study concerning the ability of an infrared sensor operating in the wavelength range of 2.68 to 2.97 microns in either medium altitude or geosynchronous orbit to detect ICBMs and short-burn missiles such as ABMs. The sensor would need to have a much higher scanning rate than the Defense Support Program satellite, which rotated six times a minute. This higher scanning rate was necessary to detect the ABMs before their engines burned out. As a bonus, the higher scanning rate would also enable the sensor to detect reentry events, such as Soviet warheads during ICBM tests. According to a memorandum summarizing the briefing from the director of the NRO (DNRO) Al Flax to the Secretary of the Air Force, Harold Brown, this would be an intelligence sensor, not one intended to directly support Air Force operations like the Defense Support Program satellites.

| Despite the highly classified nature of JUMPSEAT, a year before the first launch Aviation Week had already revealed its Air Force code number, 711, its launcher, its elliptical orbit, its contractor, and its SIGINT mission. |

Because Aerojet had their hands full with the DSP sensor, the Air Force determined that these other sensors could best be built by Hughes, and that a Lockheed satellite then being built “for another program”—almost certainly CANYON—could host them. The goal then was to have a spacecraft available in 15–18 months, presumably because of the urgency that then surrounded the resolution of the ABM controversies. For unknown reasons, the new sensor was incorporated into JUMPSEAT instead. With Hughes building both the sensor and the spacecraft, the integration task would have been simplified, although the satellites operated in vastly different orbits.

Two illustrations of the JUMPSEAT satellite. Note that they have different sensors mounted at the base of the de-spun platform. In operation, the antenna farm pointed down towards the Earth. (credit: NRO) |

Listening from on high

The NRO put increased emphasis on collecting information on Soviet anti-ballistic missile radars starting in 1967. Beginning in 1968, the STRAWMAN low-altitude electronic intelligence satellites carried a payload named CONVOY to detect such signals, and the NRO also launched at least one POPPY mission as well as small spacecraft named TIVOLI and MABELI that targeted ABM radars. Some reports indicate that JUMPSEAT was developed to detect Soviet ABM radars, partly as a consequence of a committee chaired by Harry Davis that developed a strategic plan for signals collection from space. If JUMPSEAT originated as an ABM radar detection satellite, it apparently evolved to take over most of the STRAWMAN mission, because STRAWMAN was phased out of service soon after JUMPSEAT began operating.

Despite the highly classified nature of JUMPSEAT, a year before the first launch Aviation Week had already revealed its Air Force code number, 711, its launcher, its elliptical orbit, its contractor, and its SIGINT mission to “monitor foreign radar activity.” The name JUMPSEAT was not revealed until the late 1980s, in Seymour Hersh’s book about the 1983 shooting down of Korean Airlines flight KAL 007 by a Soviet fighter plane.

A Hughes Syncom/Leasat communications satellite being prepared for launch on the space shuttle. Leasat was used as the basis for the second generation Satellite Data System relay satellites. Hughes acquired significant experience with spinning satellites and high-altitude signals and communications satellites for the National Reconnaissance Office and the military. (credit: NASA) |

After the 1971 launch, more JUMPSEAT satellites were launched in 1972, 1973, and 1975. Starting in the early 1970s, the Air Force (not the NRO) began development of a new Satellite Data System (SDS) satellite with a communications relay mission. The Air Force was responsible for developing the satellite, and the CIA was responsible for the communications relay payload. Hughes won that contract, probably helped by its experience developing JUMPSEAT. Whereas JUMPSEAT used the HS-318 satellite bus, the SDS, also known by the classified name QUASAR, was apparently based upon Hughes’ somewhat larger commercial Intelsat IV satellite bus. A later version of QUASAR was based on Hughes’ much wider Leasat satellite bus.

In June 1976, the NRO launched the first SDS data relay satellite, which operated in a similar orbit as JUMPSEAT. Much later in the 1990s, some versions of SDS added a geostationary capability. Hughes’ military and intelligence satellite work, as well as its popular Intelsat IV design, enabled the company to become a powerhouse in high-altitude satellites for the next several decades.

JUMPSEAT had a large main dish for collecting signals, and a smaller dish for relaying signals to ground stations in the United States. The dishes were on a platform that was de-spun from the satellite bus. Note the unlabeled sensor at the base of the de-spun platform. (credit: NRO) |

Known and unknown

The NRO has not released substantial information on JUMPSEAT at this time, but will review information for further release “as time and resources permit.” It did release illustrations of “the early JUMPSEAT systems” and the “early JUMPSEAT models.” They reveal a large circular dish antenna with a smaller circular dish antenna mounted above it atop a tall tower. Construction photos indicate that the larger dish was stowed in a partially folded configuration during launch and deployed in orbit. According to a source who was briefed about JUMPSEAT’s role in Operation Desert Storm in 1991, by that time JUMPSEAT’s antennas were mounted side-by-side rather than one atop the other. The purpose of this new configuration is unknown, but the company may have gained confidence from its SDS satellite operations, which required that the antennas be pointed towards different targets.

The National Reconnaissance Office released several photos of JUMPSEAT models. These models reveal features of the design. (credit: NRO) |

The illustrations of JUMPSEAT released by NRO do reveal some information not mentioned in the public fact sheet or declassification memo. Notably, the staring infrared sensor is visible at the base of the de-spun antenna platform. In one image, a second optical sensor is present. The optical sensor also appears to have another sensor mounted above this, although its purpose is unknown.

The NRO’s JUMPSEAT declassification is a start, but it will likely be several years before significantly more information is released, such as official histories, mission reports, and documents and memos. In summer 2023, the NRO declassified the PARCAE ocean surveillance satellite, but two and a half years later it still has not released any documents or even photos of the flight hardware. JUMPSEAT will remain mysterious for a while longer.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.