Small ball or home runs: the changing ethos of US human spaceflight policyby Roger Handberg

|

| The US program essentially became schizophrenic in that it built and flew the shuttle while always looking back at the Apollo program for inspiration. |

Success can be achieved either way, but one, small ball, is low budget with a smaller margin of error possible, while the second, home run, requires a significantly bigger budget in order to attract the best players. Third baseman Alex Rodriguez of the Yankees makes as much as entire starting line ups for some of the small franchises. The human spaceflight program, at least in terms of government’s involvement, is moving from the home run strategy to the small ball.

Why the change?

The foundational event in the development of the US human spaceflight exploration program remains the Apollo program, even though it was successor to the Mercury and Gemini programs. For a brief shining moment in history, the US stood on the cusp of the next great adventure in human exploration of the unknown after reaching the Moon in 1969. Unfortunately, the political support for conducting such a program into the indefinite future did not exist. Instead, the US program entered the smaller default option of building the space shuttle program. Standing alone rather than as part of a larger exploration effort was the message delivered to the space community.

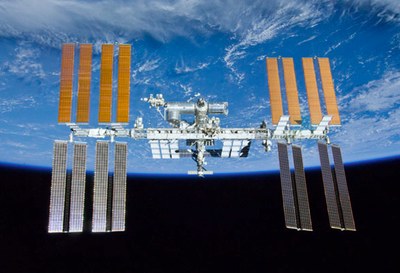

The US program essentially became schizophrenic in that it built and flew the shuttle while always looking back at the Apollo program for inspiration. The political lesson learned by NASA and much of the space community was that the human exploration effort within the United States could only be accomplished through a larger scale focused effort aimed at a specific location in the solar system: the Moon or, better yet, Mars. As the next logical step in fulfilling that vision, NASA pursued the space station relentlessly until President Reagan agreed to the program in 1984, albeit with minimal political support. That lack of strong political support plagued the project as its budget grew, leading to a steady whittling away at the station’s capabilities. The more the space station cost, the less it could do with a smaller crew. As a result, the space station was in time seen as a dead end and a program that did not take you anywhere interesting. NASA, once committed to the space station, could not admit its mistake. This may reflect a reflection of a failure of imagination by NASA and the fact that the space shuttle and space station together were coming to consume the entire NASA budget. Now NASA, despite the completion of the International Space Station (ISS), is widely perceived to have lost its way, battered by changing budgets and crushing political demands to continue constituent jobs.

The US space program remained focused, not on duplicating Apollo, but on achieving another difficult goal such as going to Mars, a logical extension truly of the Apollo effort. Twice, the presidents Bush provided the presidential rationale, if not support, for achieving great things. The Space Exploration Initiative (SEI) in 1989 and the Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) in 2004 were announced with great fanfare but neither survived the realities of congressional and presidential budgeting. The VSE appeared on paper more realistic about funding, but its choices were draconian: the ISS and space shuttle were both to be sacrificed on the altar of the new program. The earlier SEI died quickly, so hard choices were not required, while the VSE in the form of the Constellation Program lingers on although its effective demise appears certain. The Obama Administration prefers another approach while the new Congress is likely more hostile to big ticket discretionary spending. If the Tea Party faction in the Republican House caucus means what it says, the future for Constellation or any other similar program is a dim one.

The reality is that the Apollo program, the SEI, and the VSE are examples in space terms of the home run approach. Such efforts confront the cruel but obvious reality that the human spaceflight program is considered by the public and most of Congress to be a “nice to have,” but not a necessity when compared to other programs or national priorities. Congressional support is narrow and constituency-driven (i.e. protect local jobs), which means most in Congress only support the space program in the abstract. Big ticket items or programs are not a priority for most, given other priorities. What happens is what can be loosely termed normal politics: a situation where human spaceflight remains a low priority on the national agenda. Funding for bold new initiatives is going to be hard to come by even when the economy recovers and deficits are under control. The home run approach has run its course at least for a time; now the small ball approach becomes your mantra.

What this means policy-wise

If one conceptualizes Apollo as the example par excellence of the home run approach, what does the small ball approach mean for NASA? Simply put, NASA needs to think of its human space exploration effort as a process, not a project. Apollo arose from the political world rather than the logical outcome from a systematic approach to space exploration. NASA provided the substance but the president, Kennedy, was looking for flashy items to highlight US prestige and technological capabilities. The latter was particularly important since the Soviets were clearly leading the United States in the space race in May 1961. This event, Apollo, with its great success, imprinted itself into NASA’s organizational DNA: human spaceflight programs must be large scale and dramatic. That is what needs to change if NASA and its aspirations are to survive.

| Apollo was sui generis, one of a kind, a product of unique historical circumstances. NASA’s future in human spaceflight is budget wise and politically more supportable as a small ball approach. |

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden alluded to that reality recently: “Future NASA space programs must be affordable, sustainable and realistic to survive political and funding dangers that have killed previous initiatives.” This is harsh talk but it reflects the reality confronting all US discretionary programs in the federal budget. The new Republican House majority is determined to cut federal expenditures and appear to have little concern for where the cuts occur. The budget struggles this year and next will find all discretionary programs mobilizing their supporters. Competing agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF) have constituencies who are savvy veterans of getting their way even when budgets are tight. The cure for some disease is always just another appropriation away from happening.

As has been repeatedly said, Apollo was sui generis, one of a kind, a product of unique historical circumstances. NASA’s future in human spaceflight is budget wise and politically more supportable as a small ball approach. This is clearly less flashy, but today being politically sustainable must become the focus. The flexible path suggested by the Obama Administration is perceived by some as too vague and indefinite (see “Prognosticating NASA’s Future”, The Space Review, March 29, 2010). That may be an accurate judgment, but that plan envisions a process rather than a constituency or destination focus, which has been typical of NASA initiatives. Such a project or destination focus becomes finite, with an end date and no logical follow on into the future. Conceptualizing space exploration as a process rather than a destination or project allows you to build on success and push outward beyond the Moon and into the solar system.

This also accommodates the development of a commercial human spaceflight program to handle trips to the ISS or tourists going to a Bigelow space habitat. NASA human spaceflight is not crippled or destroyed by such developments. Rather, NASA clearly must focus on exploration, not running a bus service to the ISS or other orbital locations. Commercial operations will eventually go where a profit can be made; their forte does not presently include actual exploration unless heavily subsidized. Why subsidize? Costs in the human space exploration domain are not necessarily lower than NASA with regards to exploration. We are not sending ships across the ocean in pursuit of gold as occurred during the European era of global exploration. Even suggestions of going to asteroids are built around some notion of profit. This approach returns NASA to its roots as a scientific and exploration agent. The space shuttle was important in sustaining a US presence in outer space but fundamentally it was incomplete because the shuttle stood alone, a relic of Apollo and its times.

| The politics of American space policy are such that NASA has to adjust or become another relic of the Cold War. |

What this also means is that the US must become focused on maximizing its experience on the ISS. The VSE and Constellation program had no vision for the ISS: build it and then leave it to pursue the Moon or beyond. Leaving $100 billion on the table made little sense but resulted from the ISS being a compromised project once the Russians entered the program. The orbital position of the ISS was made by deliberate choice more difficult for the space shuttle to reach in the interest of fostering international cooperation. Rather than a dead end, the ISS now becomes part of this larger process of human exploration of space. The ISS provides much needed experience in long-duration flight—critical information for missions beyond the orbit of the Moon. One of the signs of the home run approach was the VSE’s willingness to write off the ISS so quickly after its completion. In fact, the US unilaterally proposed a truncated ISS construction process that would have severely damaged its partners’ programs by effectively eliminating their costly lab facilities, Columbus and Kibo. That effort was rejected. From the US perspective, rather than seen as an asset, the ISS became a burden after a hard decade long struggle to build it. The ISS became merely another project, which meant it was a dead end rather than part of an ongoing space exploration process.

The politics of American space policy are such that NASA has to adjust or become another relic of the Cold War. The project or destination mentality grew in importance for NASA because it allowed for time and cost goals to be delineated even though both have historically been fantasies used to lull Congress to sleep. NASA consistently overruns cost projections. The reasons may vary but the results are the same: more money and time always is needed. The goal was getting the project approved; the grubby details would be worked out later. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has repeatedly detailed the results: cost overruns with schedules almost completely out of control. The astronomy community is now confronting that with the $1.6-billion cost overrun for the James Webb Space Telescope, an overrun that would be devastating the rest of the scientific community. One result could be the delay in the Wide Field Infrared Telescope, which would search for dark energy across the universe.

Projects are the political vehicle for obtaining support for human exploration but, unfortunately, they carry an aura of completeness. Once the Eagle landed on the lunar surface in 1969, the Apollo program was done—subsequent missions were merely running out the string. That reality made it politically easy for President Nixon to pull the plug on the last three Apollo missions. Those missions more heavily emphasized the scientific component, but for the political class, that was at best of marginal importance. A process approach looks something like the Mars exploration effort, where a series of missions are launched, each as a building block for the next and building on past missions. Mission failures occur, but they are not the end of the story. Small ball can be as exciting as the home run approach and much more fundable, especially in a harsh budget environment that will exist for the foreseeable future.