Apollo RevisitedDancing in the pale moonlight: CIA monitoring of the Soviet manned lunar programby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Although the CIA was occasionally wrong about Soviet intentions and capabilities, they were surprisingly astute at assessing the information that they had. However, they could still miss the mark when the Soviets pulled a clever propaganda stunt. |

For instance, in November 1962 the Office of National Estimates (or ONE) wrote a memorandum titled “Possible Soviet Military Reactions to the Cuban Outcome: Gimmicks and Programs.” The premise was that the Soviet Union had been humiliated by being forced to back down from their plan to introduce medium-range missiles into Cuba and might seek to respond in various ways. One possibility, the ONE analysts suggested, could include space missions planned for maximum propaganda impact. The analysts suggested that “in 1962–1963, the following individual space missions will probably be within Soviet capabilities, although it is unlikely that they can all be accomplished during this period: multi-manned satellite; rendezvous and possible docking of two satellites; a ten-day manned satellite; unmanned circumlunar flight; unmanned satellite placed in lunar orbit; soft lunar landings of instrumented packages; planetary probes.”

What the CIA did not anticipate was a simpler stunt: the launch of the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, in June 1963.

Although short-term stunts could politically embarrass the United States, the CIA devoted greater attention to a bigger issue: the race to the Moon, prompted in part by NASA’s own interest. In September 1965, as the Apollo program reached its peak funding, NASA Administrator James Webb wrote to the CIA asking for an evaluation of “the likelihood and consequences of a Soviet program to land a man on the Moon in competition with Apollo.” Earlier that year the Office of National Estimates produced a National Intelligence Estimate, or NIE—the highest-level assessment produced by the intelligence community—on the Soviet space program. That document stated that there were no indications that the Soviet Union was competitive with the United States in the Moon race, but Webb wanted an update.

In response, the head of the Office of National Estimates, Sherman Kent, wrote a memo to Director of Central Intelligence Vice Admiral (ret.) William Raborn. This memo, which was apparently intended to be the CIA’s draft reply to NASA, was heavily based upon previous estimates, primarily the January 1965 NIE. Kent indicated that evidence gathered in the last eight months was consistent with the earlier conclusion that the Soviets were not competitive with the United States in the race to the Moon.

Kent’s memo stated: “The evident Soviet interest in lunar exploration was a factor in our judgment that the Soviets intend to undertake a manned lunar landing sometime in the future. The pace of this Soviet program, however, has been uneven, and it has been generally unsuccessful.” Kent further noted that from 1958 up to that point, the Soviets had launched an estimated 18 robotic probes to the Moon, with only three successes.

In addition, the political situation in the Soviet Union had changed. The fallout of the Cuban Missile Crisis was that Khrushchev was forced out of power and replaced by Leonid Brezhnev. Although the Soviet economic situation had not changed, the civilian and military space programs still competed for scarce high-quality resources in the Soviet economy. However, the military was receiving increasing emphasis now that Leonid Brezhnev had achieved power and this could affect funding for the Soviet civilian space program.

Kent added that “if the Soviets have not chosen to race to the Moon, we expect that they will endeavor to soften the impact of a successful Apollo mission by the achievement of other goals of their own choosing. They have openly questioned the scientific significance and necessity of a manned lunar landing, and will probably substitute goals to which they can attribute greater meaning.” These could include extensive Earth orbital operations and space stations, as well as vigorous robotic lunar exploration. Another possibility was an early attempt at a manned circumlunar mission “aimed at offsetting the effects of a successful Apollo mission and reinforcing the association of the Soviet Union with the early exploration of the Moon.”

“In sum,” Kent concluded, “we expect the Soviets to pursue a vigorous and expanding space program generally competitive in scope with that of the U.S. We do not believe that they are engaged in a manned lunar landing program competitive on the same schedule with Project Apollo, but we cannot rule this possibility out. We continue to estimate that they could achieve a manned lunar landing about mid-1969 at the earliest. If they detect slippage or stretch-out in the U.S. program, they might be moved to accelerate their own.”

Someone—perhaps the Director of Central Intelligence William Raborn himself?—added a handwritten note next to this line that “They also might not. They could slow down further.”

| “If they detect slippage or stretch-out in the U.S. program, they might be moved to accelerate their own,” Kent wrote. “They also might not. They could slow down further,” someone added. |

Although Kent was speculating, we now know that the change in political regimes in Moscow had indeed affected the Soviet civilian space program, and the lunar project was in need of funds. But those in charge of the civilian program continued to believe—self-delusion being a common feature of authoritarian societies—that they could still beat the Americans to the Moon. They continued to believe this even after the Americans further outpaced their human spaceflight program over the next several years.

Several other declassified documents provided supporting data to answer Webb’s question. For instance, a summary of comments by Soviet officials prepared in October 1965 quoted cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov in an interview with a Czech reporter. Komarov, who would die two years later when his Soyuz vehicle’s parachute failed to open, stated that if the American formula for a manned lunar landing was “1969 + X,” then the Soviet formula would be “1969 + (X–1).” An unnamed CIA official commented that “this is probably the closest thing to a date that we will ever receive openly from the Soviets.” Another CIA document, titled “Chronology of Selected Soviet Statements on a Manned Lunar Landing Since January 1965,” indicated that various Soviet cosmonauts and scientists, as well as Leonid Brezhnev himself, had spoken about their lunar aspirations, if not their specific plans, over the previous eight months. Clearly the Soviets were not completely ignoring the subject, but neither were they making it easy for American intelligence analysts to figure out what they were doing.

Despite all of this effort, no variant of Kent’s memo was ever sent to NASA. At the time, Raborn wanted to establish a Space Intelligence Panel to specifically address space topics. The Deputy Director for Science and Technology at the CIA, Albert D. Wheelon, talked to Raborn about delaying the NASA request and having the panel take up the issue as their first task. Raborn agreed that this would be the best way to proceed and obtained assurance from NASA that the agency did not require an immediate answer to its question.

The Space Intelligence Panel met for its first time in late October. Rather than the lengthy response prepared by Sherman Kent, the panel produced a two-paragraph conclusion. “It is clear that the Soviet space program is big, generally competitive, and versatile,” the panel wrote. “Its major objective is to enhance the technological and military image of the USSR relative to that of the United States by means of major accomplishments in space. It is not now possible to determine with certainty the specific direction the Soviets will take in attempting to meet this major objective.” Much hinged upon Soviet rocket propulsion developments. But the available evidence in late 1965 did not indicate if the Soviet Union was pursuing a manned lunar landing program or a large manned space station program instead. If the Soviets were indeed pursuing a lunar program, the panel concluded, “we are quite certain they are not ahead of the United States in this program but are rather from 0 to 18 months behind.”

The Space Intelligence Panel’s assessment was remarkably accurate, and over the next several years the US intelligence community continued to monitor Soviet space developments. The Soviets’ lack of manned spacecraft launches from spring 1965 to spring 1967 reinforced the impression that the United States maintained a substantial lead in the race to the Moon, even after the tragic January 1967 Apollo 1 fire set back the American program by a substantial amount.

| If the Soviets were indeed pursuing a lunar program, the panel concluded, “we are quite certain they are not ahead of the United States in this program but are rather from 0 to 18 months behind.” |

In October 1967, the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence produced an overview report called “The Soviet Space Program Ten Years After Sputnik I” (see “In Apollo’s shadow: the CIA and the Soviet space program during the Moon race,” The Space Review, May 13, 2019.) It stated that “some see the Soviet space program as only a scheme to capture spectacular headlines, some consider it an exclusively military effort, and some others view the past ten years as an orderly unfolding of a long-range master plan with neither false steps nor blind alleys. The Soviets themselves frequently have characterized their program as purely scientific and not competitive with that of the U.S.” But the CIA document stated that “none of these diagnoses is completely right or wrong.” Although they had achieved spectacular headlines with some of their achievements “a creditable number of Soviet flights, on the other hand, quietly made solid contributions to man’s understanding of the cosmos.” It added that “certain segments of the program have indeed exhibited a high degree of orderly planning and intelligent execution; but there have been dead ends, blunders, and even disasters.”

The comparison of this ten-year overview with the agency’s specific response to James Webb’s late 1965 request for information on the Soviets’ lunar progress highlights the fact that fortunes could reverse quickly in the space race. Whereas Sherman Kent’s September 1965 memo had noted the large number of Soviet lunar probe failures up to that time, what the CIA could not foresee was that the Soviets would soon accomplish a string of lunar probe successes. Only a few months after Kent’s memo, in January 1966 the Soviet Union soft-landed Luna 9 on the Moon. “The Soviets were surprisingly slow in correcting the deficiencies plaguing this program, a failing that has been noted in other parts of the space effort too,” the 1967 overview explained. But the Soviets soon followed Luna 9 with three successful orbiters (Lunas 10–12) and another soft-landing with Luna 13.

The retrospective ended with a discussion of the large Soviet rocket that was then under development at the launch complex at Tyura-Tam (now known as Baikonur). Although CIA analysts still believed that the rocket could be used for launching a space station as large as 113,000 kilograms into low Earth orbit, “a manned lunar landing is, nevertheless, the most likely focus of Soviet attention in the next five-year period,” the document concluded.

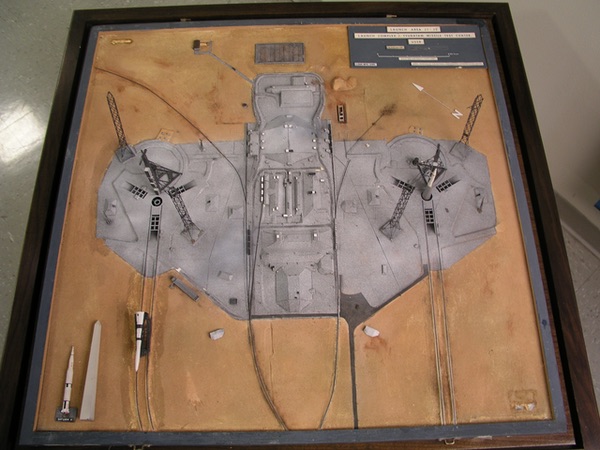

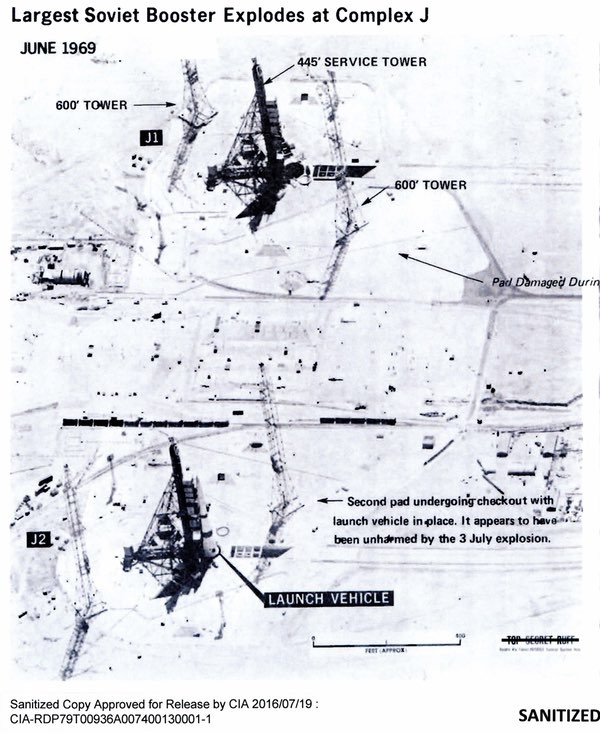

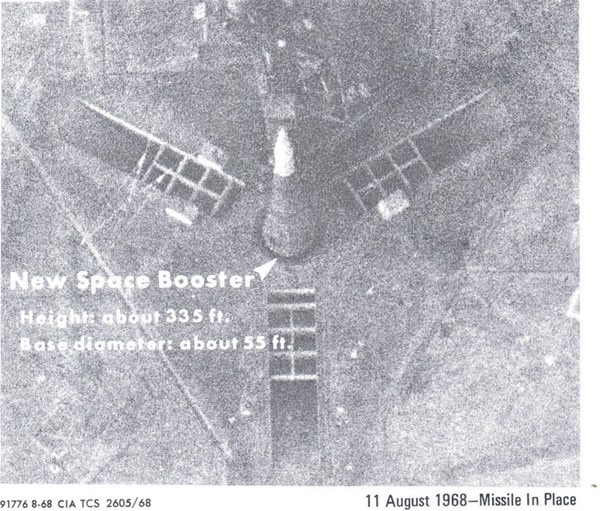

Over the next several months, American intelligence satellites spotted significant developments at this large rocket complex (see “Rockets, real and model-sized,” The Space Review, July 3, 2006.) In March 1968, the Guided Missile and Astronautics Intelligence Committee issued a report on Soviet surface-to-surface missile deployment that also discussed the Soviet facility, which the CIA had designated Complex J. Two large launch pads were under construction there and the service tower at the first pad had reached a height of about 135 meters, and was apparently complete because the construction crane that erected it was being dismantled. Two 180-meter tall lightning towers had also been constructed near the pad. The second pad, designated J2, was still under construction and the base of its service tower was nearing completion. All of the buildings between the two pads had been covered over with earth and a protective material.

The two N-1 launch pads photographed by an American KH-8 GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite in June 1969. At the time, the US intelligence community referred to Baikonur as “Tyuratam,” and the N-1 as “the J-vehicle.” This image does not show the damage to one of the pads that occurred on July 3 when an N-1 rocket exploded, but was used in an intelligence report to illustrate the facility after the event. |

But the real jackpot had come when an American reconnaissance satellite had photographed a launch vehicle nearly 100 meters high erected on the completed pad. The CIA’s analysts speculated that this was a mockup being used to check out the launcher and its equipment—just as NASA had done with the Saturn V. “We think that several more months of equipment installation and checkout are required and that the Site J1 will be ready to support firings about mid-1968.”

American reconnaissance satellites were so powerful that they had detected an array of telemetry antennas on top of the roof of the complex’s giant assembly building. “Outside this building a probable missile transporter was observed. Approximately 200 feet [60 meters] long by 85 feet [25 meters] wide, the transporter appeared to be constructed of heavy steel members with one end elevated. Nearby another transporter was being assembled. Construction was continuing on the Complex J spacecraft facility.” The exterior of the building was complete and construction probably continued inside.

|

Despite all the recent progress at the launch site, there were no indications that the Soviet Union was gaining on the United States. The United States had already perfected rendezvous techniques with the Gemini program and was making substantial progress at fixing problems with the Apollo spacecraft. Komarov’s April 24, 1967 death was in some ways a greater setback for the Soviets than Apollo 1 was for NASA. As a result, by the summer of 1968, NASA officials and the CIA turned their attention to the Soviet circumlunar program, an effort to send a man around the Moon. If successful, the Soviet Union could upstage the Apollo landing then scheduled the following year. By summer 1968 NASA officials made a bold decision to send the Apollo 8 mission around the Moon.

The major outstanding question of the influence of intelligence collection on the Moon race is the extent that intelligence information on the Soviet Zond circumlunar missions prompted NASA officials to make the Apollo 8 decision. To date, the evidence supports the conclusion that although the Zond program was a factor in the Apollo decision, it was a supporting factor, not the sole or decisive one. Apollo was already going flat out, pedal to the floor, within the limits of safety. NASA officials were less concerned with looking over their shoulder than maintaining control of a massive bureaucratic, managerial, and development machine that they were pushing to its limits. The Apollo 8 lunar module was not ready for its test flight, and NASA officials were unwilling to delay the mission in order to wait for the lander. They decided to send the astronauts around the Moon rather than simply into Earth orbit.

Declassified documents provide one piece of evidence on this issue. During a regularly scheduled morning meeting of CIA officials in late October 1968, the Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Carl Duckett (who had replaced Albert Wheelon several years before) “remarked it is plain that NASA’s plan for a manned circumlunar launch in December is a direct product of an earlier intelligence briefing on Soviet space intentions.”

| Even if NASA officials were seeing the raw intelligence that the CIA, NSA and even the US Navy were gathering about Soviet space efforts as soon as it was gathered, they certainly could not move any faster than they already were moving. |

That was perhaps a bit presumptuous: there was no way for Duckett to know all of the factors that NASA officials had considered when making their decision, or what had been most important to them. The existing evidence suggests that the lunar module delay was what kicked off the decision process, and apparently drove it. Other evidence indicates that an Apollo circumlunar mission had been first discussed within NASA as a possible option as early as spring 1968, before there was any substantial concern about a Soviet manned circumlunar flight. NASA certainly did not require any special intelligence briefings from the CIA in the summer of 1968 to know that the Zond missions were occurring, since information about them was reported in the press.

Even if NASA officials were seeing the raw intelligence that the CIA, NSA and even the US Navy were gathering about Soviet space efforts as soon as it was gathered, they certainly could not move any faster than they already were moving. Like a runner on a straight track, the NASA leadership was more focused on what was ahead than who might be right behind them. Landing on the Moon was the finish line, and everybody on Apollo was focused on reaching it.

A recent article in a new Russian space magazine, Russkiy kosmos, was based upon past Space Review articles about US intelligence and the Soviet N-1 program. |

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.